Reclining women: The ultimate expression of wealth

Private planes, fast cars, yachts, diamonds and fancy watches – we know the signs of wealth when we see them. But have you ever considered that status symbols vary greatly across cultures, and that indications of luxury have varied historically?

Private planes, fast cars, yachts, diamonds and fancy watches – we know the signs of wealth when we see them. But have you ever considered that status symbols vary greatly across cultures, and that indications of luxury have varied historically?

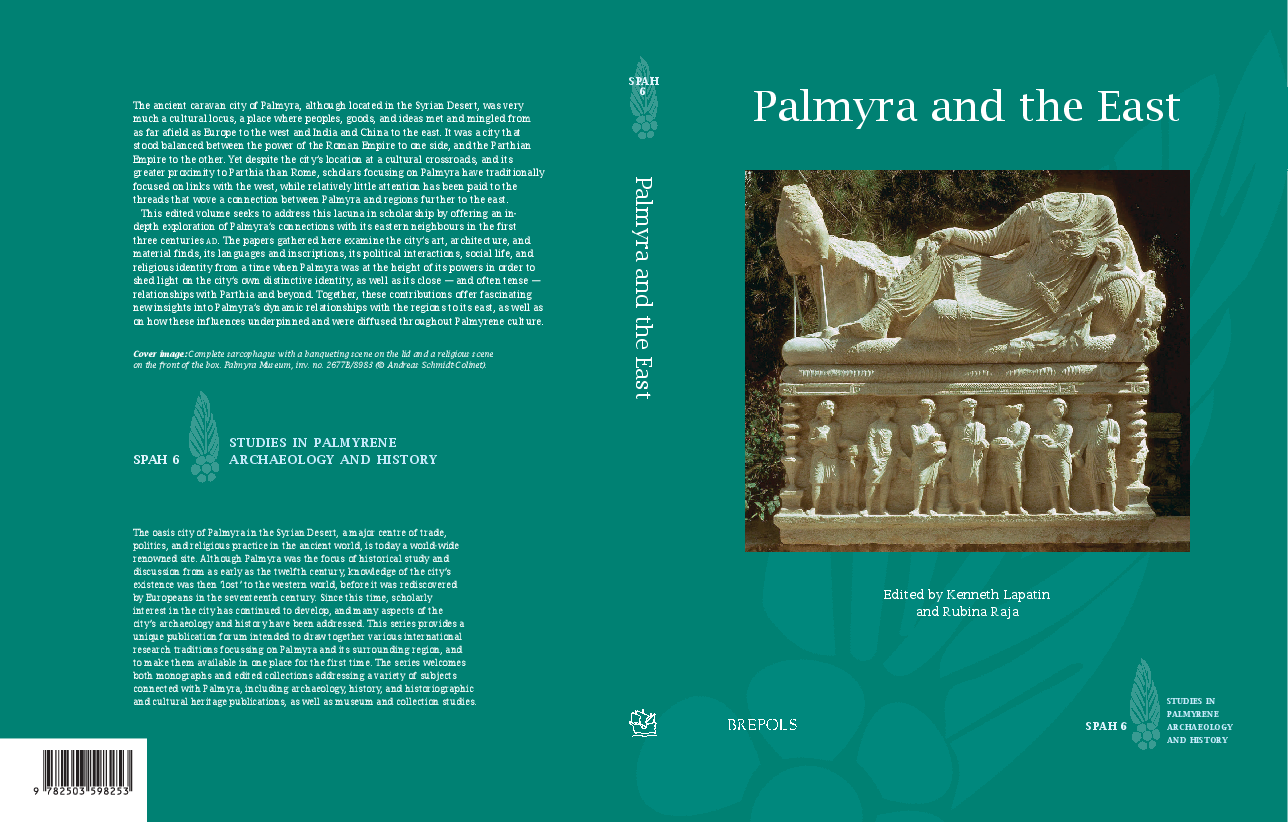

We have all seen images of Scrooge McDuck doing backstrokes in his money bin, but for inhabitants of Palmyra in Syria throughout the first three centuries CE, such an image would pale into insignificance compared with the portrait of a woman reclining on a couch. In fact, the notion of depicting a reclining woman was considered a sign of such high status that it was reserved for the uppermost layers of the Palmyrene elite – and even then, it was only to be looked upon by a highly restricted audience.

In a new paper, Rubina Raja examines the motif of reclining women in Palmyrene funerary art. The study is made possible by the work of the Palmyra Portrait Project (directed by Raja and funded by the Carlsberg Foundation), in which all known portraiture from Palmyra has been collected and compiled in a single database. By far, the most depictions of women in the corpus allude to the female role of wife, mother and domestic carer, and traditionally women are shown wearing veils and doing special gestures that were defining of ‘womanhood’. However, a very small subset of the portraiture (13 out of more than 4000) is of women reclining in a banqueting scene – a motif traditionally reserved for depictions of men, and most often priests, indicating the extremely rare nature of women in this sphere of art.

How can this be explained? And how did this motif come about? Well, we know that these women were part of the absolute elite of Palmyra, in that all 13 stem from the most exclusive grave monuments in the city – graves where only close family were allowed to enter. All wear fine clothing and elaborate jewellery, and the mattresses and pillows upon which they rest are highly decorated, emphasising their belonging to the highest circles of society. Traditionally, Palmyrene art has been interpreted through the lens of Roman influence and rulership; however, the city had close ties with the East, where the banqueting motif is well known from elite culture, and in this light, the depiction of reclining Palmyrene women can be understood as a way of individualising the otherwise highly standardised banqueting scene.

The chapter is part of the volume Palmyra and the East, edited by Rubina Raja and Ken Lapatin (The J. Paul Getty Museum), which stems from an international symposium held in 2019 at the Getty Villa in Los Angeles, USA. This event brought together some of the world’s leading experts on Palmyra (from art and architecture to the social, economic and religious life) and offered entirely new interpretations of Palmyrene culture, as understood through explorations of the East and the cross-cultural encounters that were bound to have taken place in what was arguably one of the greatest melting pots of the time.

Lapatin, K. and Raja, R. (eds). 2022. Palmyra and the East, Studies in Palmyrene Archaeology and History, 6 (Turnhout: Brepols).

Raja, R. 2022. ‘Palmyrene funerary art between East and West: Reclining women in the funerary sculpture’, in Lapatin, K. and Raja, R. (eds), Palmyra and the East, Studies in Palmyrene Archaeology and History, 6 (Turnhout: Brepols), 71–96.