Palmyra’s Little-Known Neighbour: The Sculpture of Osrhoene

by Nathalia B. Kristensen and Jesper V. Jensen

Michael Blömer, assistant professor at Centre for Urban Network Evolutions, Aarhus University, gave an interesting lecture about the sculpture of Osrhoene. The lecture gave cause for further reflection, since not much research has been done on this group of sculpture and the region of Osrhoene.

Osrhoene was a kingdom situated in Northern Mesopotamia, which today covers the border area between Turkey and Syria. The kingdom was formed after the Seleucid Empire lost control over Mesopotamia, and it became an independent kingdom although heavily influenced by the Parthian Empire to the east. Its position between the Roman and Parthian Empire was both fortunate and unfortunate. In times of peace, it was a trade centre between East and West, but in times of war, it became the centre of hostilities between the two rival powers. It was in around 200 CE that it was turned into a Roman province. In the Byzantine period, it became a religious and cultural centre for Eastern Christianity, and later, it became part of the Ottoman Empire.

Before the World War I, many scholars – including philologists and linguists – traveled through the region and were able to study the region as a whole. After the war and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, this became difficult because of the new borders splitting the region of Osrhoene in two. This means that very little archaeological material, including sculpture, has been published, and it is therefore often neglected or ignored in a larger context.

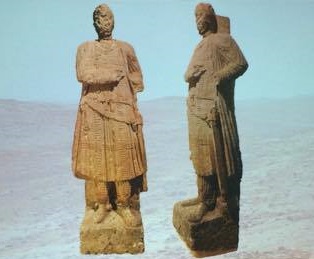

Most of the sculpture available for further studies stems from funerary contexts, especially the Turkish excavation of the necropolis of Edessa, the capital of Osrhoene. Two over-life-size statues of men in tunics and trousers richly decorated in the “Parthian style” were found on site as well as funerary portraiture of men and women and banqueting scenes. The closest iconographic reference seems to be the sculptures of Hatra and of Palmyra. Only few similarities can, however, be seen in the sculpture of neighbouring North Syria. This has traditionally been attributed to the “Parthian” influence of Mesopotamia, whereas the sculpture west of the Euphrates has been influenced by the Roman Empire.

Blömer argues that it cannot be that simple. We need to rethink this traditional mindset, because although there are stylistic similarities, there are also distinct differences between the regions in Mesopotamia. We need to stop using terms such as “Parthian” and “Roman” and instead use a much broader term like “Northern-Arab”, since the area has a distinct iconographic style which is often overlooked. We need to look at the region of Osrhoene as a whole and not just individual cities influenced by the Parthian Empire.