Highlights from the conference "Palmyra and the East"

By Research Assistants Olympia Bobou, Rikke R. Thomsen, Nathalia B. Kristensen and Jesper V. Jensen.

The conference Palmyra and the East was organised by the J. Paul Getty Museum and Aarhus University, and was co-funded by the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Carlsberg Foundation. It took place on April 18th and 19th and was structured around four sessions: Location, Art, Religion, and History.

The conference started with the session on location. After a short welcome by the president of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Jim Cuno, and the co-organiser Kenneth Lapatin, the first paper was given by Professor Rubina Raja (UrbNet/Aarhus University) on Palmyrene Art and the East. Professor Raja talked of the importance of re-examining Palmyrene Art thanks to the work done under the aegis of the Palmyra Portrait Project, spear-headed by her and funded by the Carlsberg Foundation. In her presentation, Professor Raja highlighted the various aspects of Palmyrene art that have survived from the public and funerary sphere, and set it first in its local context, and then in the wider geographical context, emphasising the understudied links to the east.

In his presentation, Khodadad Rhezakani (Princeton University) re-evaluated the notion of the ‘Silk Road’ and Palmyra’s role within it. By highlighting our Western historiographic biases created in the post-15th-century period of great discoveries that emphasised the role of maritime trade, he challenged the idea of the predominance of maritime trade and travel in antiquity. Instead, he proposed that we need to consider the multitude of roads leading from the east (China) to the west. Instead of seeing the ‘silk road’ as a route with a preconceived beginning and ending, we should rather see it as a network of places where trade was conducted as one activity among many. We should also take into consideration the local and mid-distance routes and start considering the cities as individual places of trade, and not only a stop on a trade route.

Touraj Daryaee (University of California, Irvine) explored the relations between Palmyra and other so-called caravan cities. The attack of various caravan cities along the Euphrates and further to the west by the Sassanians has been seen either as predatory or as an attempt to return to the previous Achaemenid borders. Perhaps, though, there is another reason for these attacks: the need to destroy Arsacid trade networks and cities in order to prevent Arsacid re-emergence of power, and thus bringing these regions under direct Sassanian control. The campaigns of Odainath against Shapur I were a means of protecting Palmyrene trade interests.

Katia Schörle (Brown University) presented a broad overview of Palmyrene maritime trade through the evidence of reliefs and inscriptions. The relief from the tomb of Julius Aurelius Marona reveals that Palmyrenes owned large ships that could trade precious objects, while inscriptions show a change in routes in response to Sassanian aggressive policies and trading competitions.

Jean-Baptiste Yon (Laboratoire HiSoMA) explored the epigraphic evidence for Palmyrene trade. There is evidence for contact between Palmyra and other regions already in the Hellenistic period, but it is in the Roman period that Palmyrene trade really becomes a source of wealth for the city. The evidence shows the connections to the Persian Gulf and the Indian coast as well as the impact of the Sassanian expansion on Palmyrene trade routes. Inscriptions show that both land and maritime routes were important for Palmyrene trade.

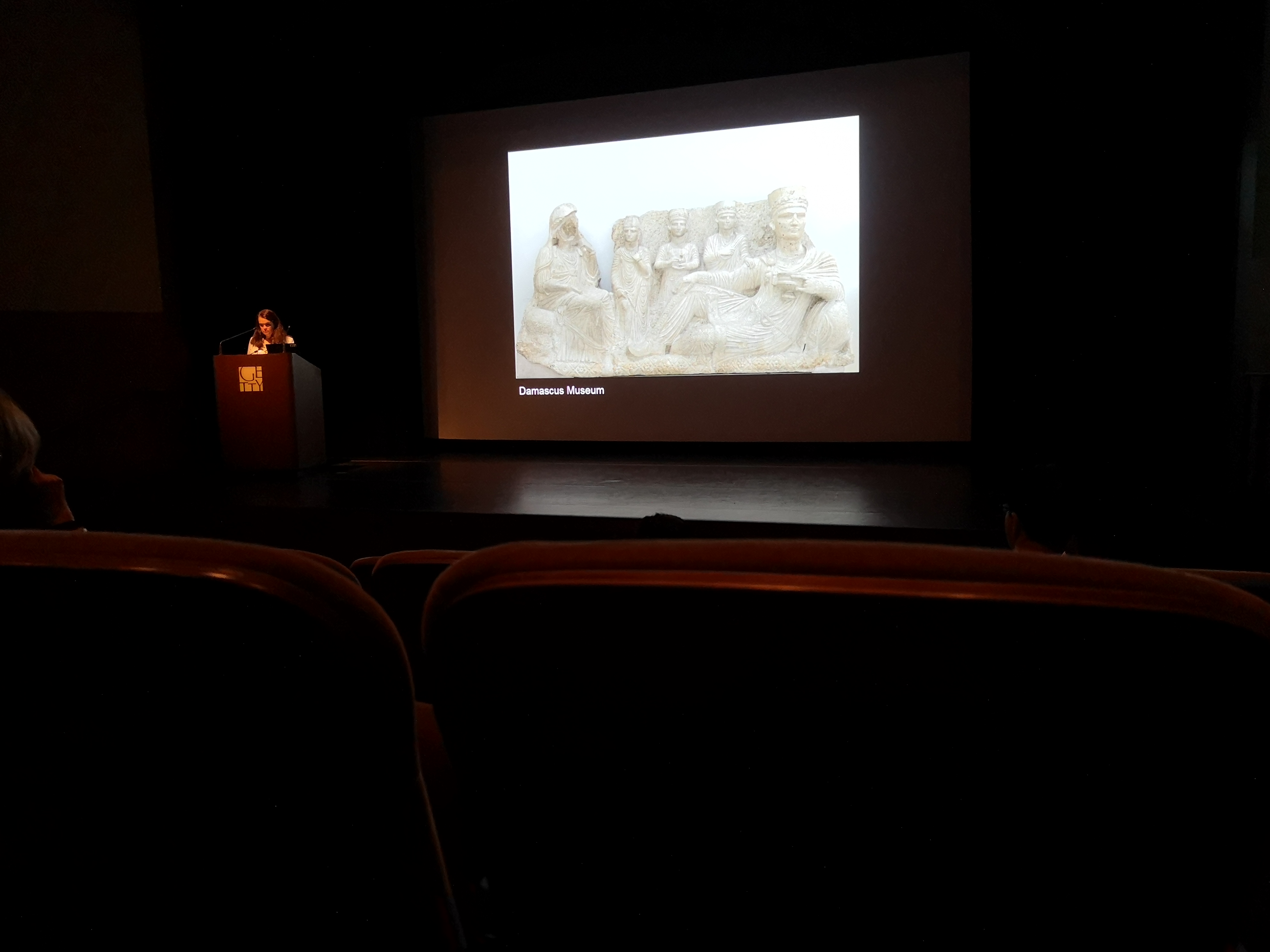

The second day started with a session on Palmyrene art. Maura Heyn (University of North Carolina, Greensboro) explored the motif of the reclining figure in banqueting scenes. Banqueting scenes have a long tradition in the Near East, with the relief showing king Assurbanipal’s victory banquet from Nineveh considered one of the most influential of such scenes. Literary evidence from Assyria suggests that only the king could recline at a banquet. Iconographic evidence from Anatolia and Persia shows the courtly fashion for holding the skyphos with the fingertips. At Palmyra, we see allusions to aristocratic, or high social status, by showing the main figure as reclining, holding the skyphos with the fingertips, but also to religious activities, through the use of specific costumes. Thus, the Palmyrene banqueting scene can be considered as a sort of collage that, drawing from various iconographic traditions of the wider region, includes different elements representing prestige.

Fred Albertson (University of Memphis) examined the image of young standing males carrying various objects in Palmyrene funerary art (in banqueting but also religious and trade scenes). These have been identified as ‘servants’ or slaves, but Alberton challenged this identification. He pointed out that all the figures belong to the same age group, they have hairstyles that can be associated with riding gods, they wear clothes that are similarly richly decorated as those of the main figures, as well as carrying swords and daggers. Furthermore, in religious scenes from Dura-Europos, sons of the family take on the role of attendants in sacrifices. Therefore, these young men in Palmyrene funerary art should be understood as sons of elite families, participating in religious or other activities together with other family members, whose role can be compared to that of the Camillus in Roman religion.

Lisa Brody (Yale University) presented the statue of a child found in three fragments, two from a house and one from the Agora of Dura-Europos. The child is depicted in the typical way for Palmyrene children, with a long dress, jewellery, and holding a bird and a bunch of grapes. The difficulty of identifying the gender of children based on iconography was highlighted. The statue’s place in the art of Dura-Europos and its relation to Palmyrene art have been matters of debate since its discovery. In 2018, the stable isotope signature of the stone was analysed; the examination revealed that the object was made of Palmyrene limestone, and reveals the links between the city of Dura-Europos and Palmyra.

Michael Blömer (Aarhus University) presented the art of Edessa and Palmyra in the first three centuries AD and questioned whether we should call this art ‘Parthian’, as it has been done by scholars. Despite the differences in style and costume details, both at Edessa and Palmyra we see the same concepts of virtue in men and women. These costumes, especially the riding costume worn by men has been characterised as ‘Parthian’, although they have a long tradition in the region, long before the arrival of the Parthians. These garments should not be seen as markers of political allegiance to Parthia, as it has been suggested, but instead as expressions of the revival of a long, iconographic tradition of the Syro-Mesopotamian region, shared by the people in the region and perceived as local.

The third session was on the religion of Palmyra. Ted Kaizer (Durham University) presented the evidence for the visibility of gods outside their sanctuaries in Palmyra. Mosaics with images of myths showed some of the Greek gods who had become assimilated to local Palmyrene gods. Reliefs and tesserae showed images of gods, while busts placed on arches may also represent gods. From the religious reliefs from the temple of Bel, however, we see that the images of the gods could be covered when in procession outside the temple. Perhaps these divine manifestations were the result of a different religious mentality than in the rest of the Roman Empire.

Catherine Bonesho (University of California, Los Angeles) presented the evidence for the use of Palmyrene Aramaic inside and outside Palmyra. By examining the location of the inscriptions and the relation between Palmyrene Aramaic and non-Palmyrene Aramaic texts, she proposed that we should see the use of Palmyrene Aramaic as a conscious decision of Palmyrenes to maintain and contrast their identity to Greek and Roman identity, but also as a marker in the east.

The last session was dedicated on the history of Palmyra. Nathaniel Andrade (University of Binghampton, NY) presented a vivid portrait of Zenobia through various sources and explored her policies in relation to the eastern neighbours of Palmyra. He argues that Zenobia’s relations to the East were guided by trade considerations rather than military strategy.

Emanuele Intagliata (Aarhus University) gave an overview of what is known about Palmyra after the fall of Zenobia. Even through Palmyra lost its importance as a commercial centre and its links with the east, it maintained the connection to the west as a military base on the eastern frontier of the Roman Empire. Churches and richly decorated houses show the presence of a local elite. It was not until the Islamic period that the city revived the commercial connection to the east, becoming a centre of the Umayyad Caliphate.

There was a session of questions and answers after each paper, stimulating discussion and illuminating aspects of the topics. The conference ended with a reception that allowed for further discussions. A publication based on the papers will follow in due course.