At the drop of a hat: Portraits from the past

Royals have done it since the 15th century. Later the tradition was adopted by heads of state. And today rulers, celebrities and ordinary people alike make frequent use of this practice. Requesting the creation of portrait art has, for many years, been a most favoured way of immortalising oneself or a family member.

Royals have done it since the 15th century. Later the tradition was adopted by heads of state. And today rulers, celebrities and ordinary people alike make frequent use of this practice. Requesting the creation of portrait art has, for many years, been a most favoured way of immortalising oneself or a family member.

And, perhaps not surprisingly, the act of commissioning a portrait is even known to have been widespread in the heyday of one of the most well-known and culturally important ancient cities in the world, namely Palmyra in Syria.

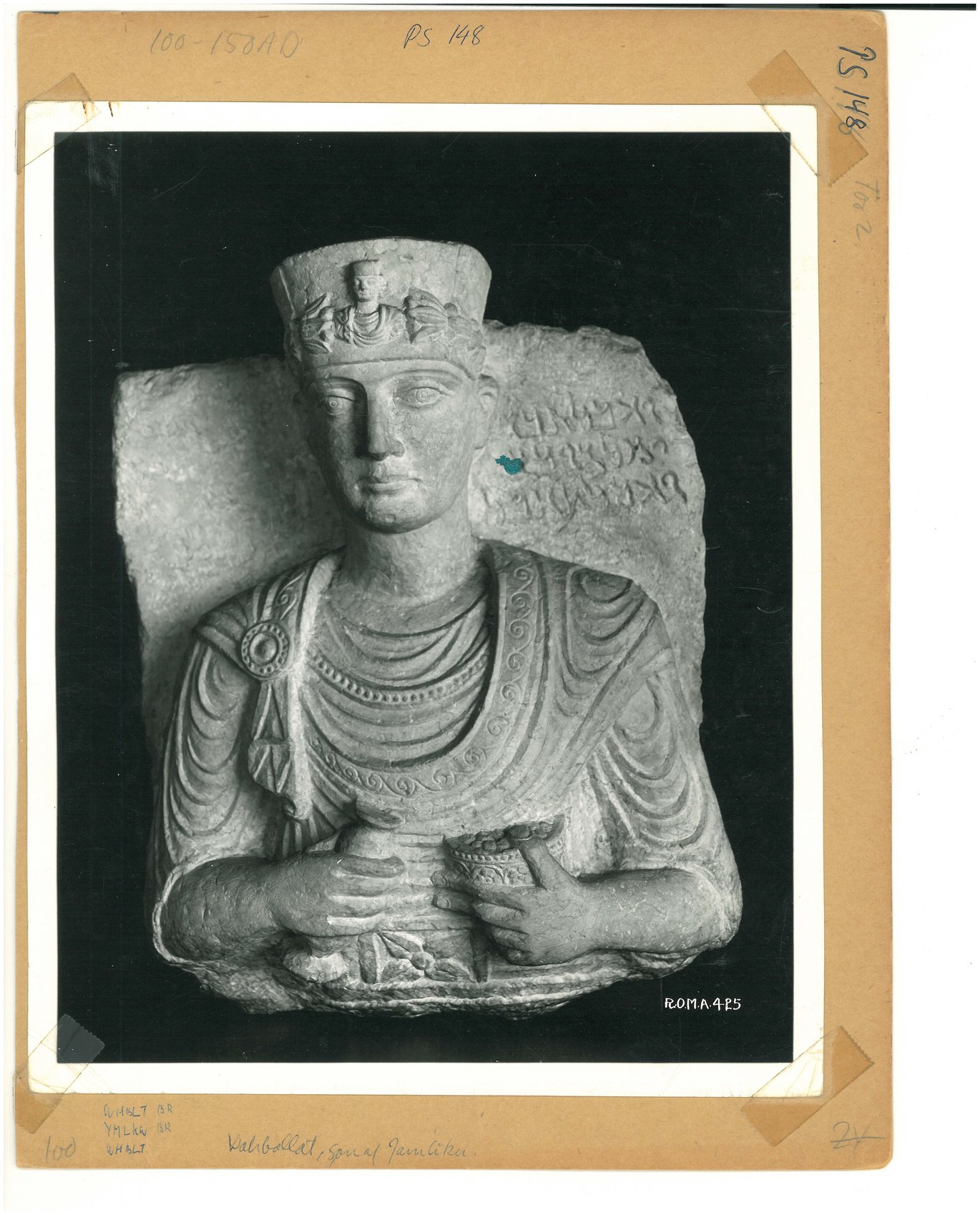

During the first three centuries CE, the production of limestone portraits was abundant in Palmyra. Studying the thousands of representations of men, women and children can shed light on both cultural and societal developments as well as local identities in the oasis city, and recent scholarship has made important strides towards understanding more fully the famous Palmyrene portraiture. In the funerary sphere, the limestone portraits constitute a unique amalgamation of local and non-local trends, and they reflect conscious choices pertaining to style, fashion and cultural values, which can be traced across more than three hundred years.

With the establishment of the Palmyra Portrait Project in 2012 (directed by Professor Rubina Raja and funded by the Carlsberg Foundation), a targeted research programme has been devoted to documenting all known funerary portraiture from Palmyra. Currently the project database contains more than 4000 individual portraits, which have been catalogued, dated and analysed by an international team of specialists. Based on the work of the project, it has become increasingly clear that the limestone portraits offer rare insights into perceptions of identity and relations reaching far beyond the city.

The focal point of this chapter is the Palmyrene priestly hat. To the untrained eye, it might seem an insignificant piece of clothing, but to scholars of Palmyrene art and archaeology, it contains a wealth of information. Much more than being a trivial type of headdress worn by an exclusive professional segment of Palmyrene society, Raja argues that the priestly hat signifies the owner’s affiliation with the uppermost layer of the societal elite of the city. Most of the Palmyrene priestly portraits include additional attributes and statements that help secure the viewer’s recognition of this being a depiction of a priest – e.g. occasional inscriptions in Palmyrene Aramaic – but the hat features as the single most distinguishable marker in the funerary corpus of elite belonging.

Although generally depicted conservatively, the hats vary greatly in style and degree of decorative details, and Raja here proposes a novel typology of this special attribute. And regardless of the specific choices of the commissioner and the artistic execution of the sculptor, the priestly portraiture expresses a strong fusion of local tradition and foreign influence – a unique Palmyrene identity.

Raja, R. 2022. The way your wear your hat: Palmyrene priests between local traditions and cross-regional trends, in U. Hartmann, F. Schleicher and T. Stickler (ed.) Imperium sine Fine (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer), 81-118.