Wilsonianism from beyond the Grave – Report from the President’s Deathbed

Emil Eiby Seidenfaden (PhD Student - Aarhus University)

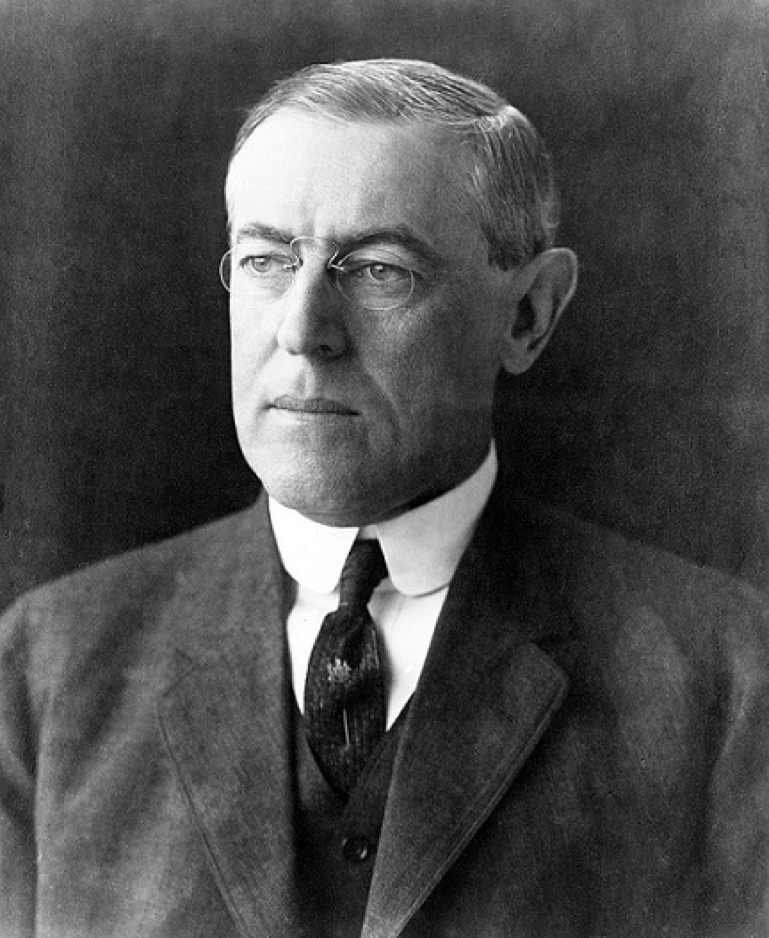

On February 3rd, 1924, former US President Woodrow Wilson died in his home in Washington D. C. President Wilson had led America through the First World War and initiated the founding of the League of Nations, but had failed to convince the US Congress to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, thereby leaving his country outside the organization whose administration is the topic of our project The Invention of International Bureaucracy.

Some time ago I visited the Library of Congress in Washington D. C. to look at the papers of Arthur Sweetser, the official of the Secretariat’s Information Section with special responsibilities for the United States. The President’s death has left an echo in Sweetser’s correspondence, in a way that demonstrates how internationalists affiliated with the League would draw on powerful internationalist voices, like Wilson’s, to promote the League. As the organization failed to handle various international crises during the 1920s, and was consequently criticized in the press, its adherents found it increasingly necessary to remind the world of the idealist thinking that sparked its foundation. The death of Wilson, leading League proponents thought, offered an opportune moment for such a reminder.

This endeavor exposed some of the dilemmas facing the promoters of the League: How could an organization whose main claim to legitimacy was its neutrality and professionalism, defend itself to public opinion without compromising this claim? And how could it work to inform about its work in a country like the United States, where fierce isolationism had prevented its League-membership, without being charged with illegitimate interference in American politics? As we shall see, the League’s promoters worked their audience indirectly: Actual propaganda for the League should preferably not be traced back to the Secretariat but instead be disseminated through “friends of the League,” and if an American audience was the target, these friends ought to be Americans, living and working on US soil, so as to make the direct connection with the League as obscure as possible.

Portrait of Woodrow Wilson 1912

The Sweetser-Fosdick connection

America’s involvement in the planning of the League’s creation, combined with its ultimate rejection of membership, left a small group of its citizens in the strange position of being affiliated to an international organization which did not have their own country as a member. A peculiar link across the Atlantic was one of the results: The ongoing correspondence between Arthur Sweetser, the League Secretariat’s special US liaison officer, and Raymond B. Fosdick. Fosdick, had initially been appointed deputy-secretary general of the League, but had to resign upon America’s withdrawal. However, he continued to discuss US sentiments about the League with Sweetser, and the two men schemed continuously about ways to influence the public and break down the isolationist hold on their country. Fosdick was enthusiastically internationalist and an influential figure in American society. He worked for the Rockefeller Foundation (and later became its president) – a fact that was probably not detrimental to John D. Rockefeller’s close association with the League and his several acts of generosity to its workings in Geneva – for example his donation of two million-dollars to the League’s library in 1927.

Raymond Fosdick (left) and Arthur Sweetser

Raymond Fosdick (left) and Arthur Sweetser

Wilson’s last words on the League

Also, Fosdick had been a friend of President Wilson,[1] which brings us to our story: Three days after Wilson’s death, Fosdick wrote a letter addressed to Secretary-General of the League Sir Eric Drummond. He sent the letter to Sweetser, asking him to pass it on to the chief. In the letter, Fosdick recounted two occasions on which he had visited the dying ex-President. During the second-last and last visit, Wilson had spoken with concern about the risk that the League would be: “tempted into compromise that would undermine its moral force. […] Don’t let the League ‘scuttle’ or ’cringe’ he said. It is the biggest spiritual asset in the world today.”[2] During their reported conversation, the feeble but eloquent statesman expressed a high-minded belief in the organisation’s potential and a conviction that America would eventually come around and support it:

“as to America’s ultimate adherence to the Covenant of the League, he entertained not the slightest doubt. […] America could not afford to play the laggard. It was the greatest moral issue that had been presented to the conscience of this nation since the question of slavery.”[3]

Fosdick seemingly sensed a possibility of utilizing the moment to the benefit of this higher cause: reminding the world public of their moral obligation to the League in preventing a new world war. He wrote, first and foremost, to thank Drummond for a previous official statement he had made on behalf of the Secretariat to the memory of Wilson. But Fosdick added in his accompanying note to Sweetser that “if Drummond wants to make any particular use of this letter, there is no reason why he should not do it."[4]

Sweetser took Fosdick’s suggestion to the Secretary-General, asking him if they could possibly have it published through the press under the cover of an anonymous headline like “From an American in New York to a friend in Geneva.” He suggested the Swiss paper Journal de Genève, (which had put its columns at the disposal of the Secretariat for “any service that you [the Secretary-General] might consider useful. Anything you wish to communicate”)[5] together with the British Headway and some yet-to-be-determined French paper.[6]

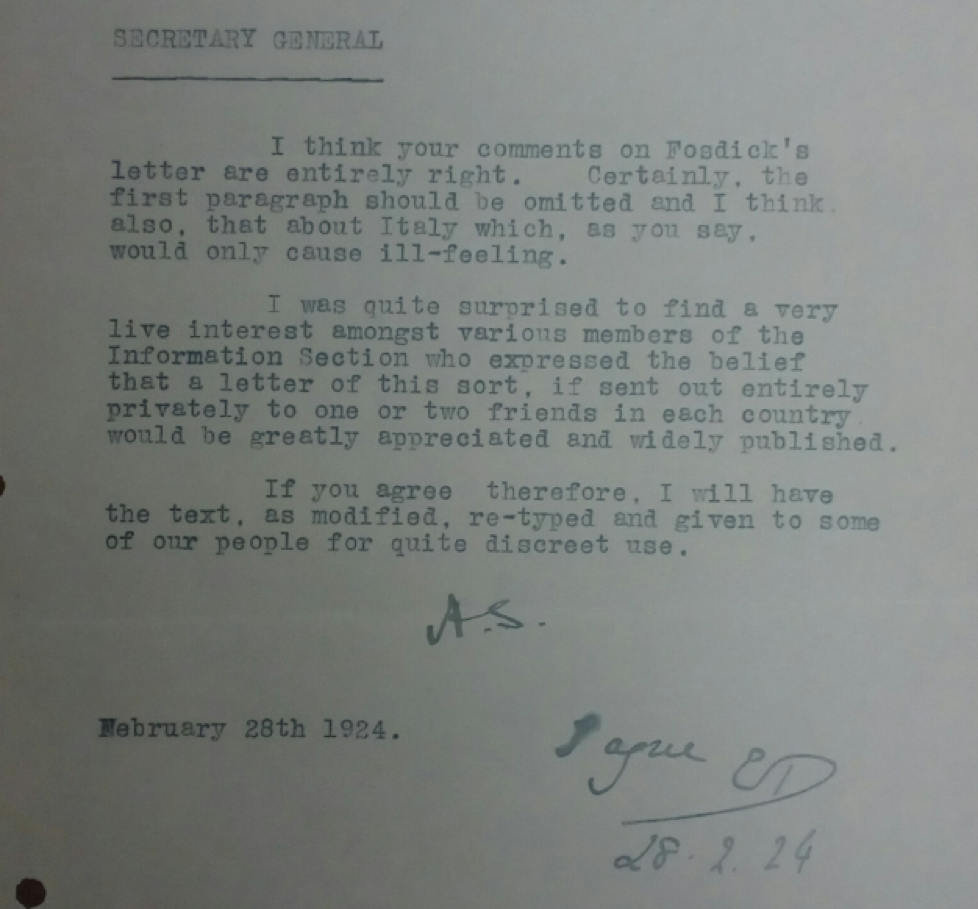

The Secretary-General scribbled back on Sweetser’s note that if the letter was to be published he should prefer some of the things Wilson had allegedly said about the League’s impotence in the Corfu affair two years before to be omitted, since they might “awake certain feelings”. The Corfu affair in 1923 had been an embarrassment to the League, because the crisis following the assassination of Italian officers on Greek soil and the following Italian occupation of Corfu had remained unresolved by the League until the Conference of Ambassadors (successor to the pre-League Supreme War Council) settled it, much to Italy’s favor. Drummond added a few other things he would prefer to be left out. With those reservations, the plan would have his blessing. Sweetser agreed to the editing and mentioned that “various members of the Information Section […] expressed the belief, that a letter of this sort, if sent out entirely privately to one or two friends in each country, would be greatly appreciated and widely published.” He therefore also secured Drummond’s permission to have the text “given to some of our people for quite discreet use.”[7]

Letter from Sweetser to Eric Drummond, with Drummond's approval written on.

Transatlantic lobbyists

On first sight, the episode provides insights into important aspects of the League’s legitimization effort: The role of Arthur Sweetser as a lobbyist working the highest echelons of American society has been discussed earlier by Madeleine Herren and Isabella Löhr.[8] It provides us with an interesting look into the relative liberty of one official, who was trusted by the Secretariat to exploit his network to enhance the League’s standing in America, both publicly and among political elites. This is of great relevance to this researcher’s project on the legitimization strategies of the League, although it may not be representative of the League’s general work within this area. The episode furthermore exemplifies the work done by Fosdick, whose interwar career has been described as “a fifteen years single-minded fight to bring the United States into the League.”[9] Moreover, it casts a light on some of the paradoxes faced by promoters of the League: How could one use an endorsement from a League-idealist like Wilson while omitting the President’s core message: That the League risked making itself irrelevant if it kept backing off in crises like the Corfu affair. Thus, we are shown two different yet overlapping elements of how the League promoters worked.

The art of subtle circulation

We are shown the cautious strategizing of the Information Section and the constraints put on them from several sides: The Information Section was meant to be the point of contact between the League and public opinion, and, among other tasks, they were expected to publish informative material about the work of the organization. Although ‘propaganda’ was a word they often used in private correspondence and confidential memos, they were not supposed to take part in it officially. Thus, the wording of the letter may not seem overly controversial to us, but the crux of the matter was the use of it. It would be stepping over the line if it was distributed by the Secretariat through its Information Section. Furthermore, the ambitions of Sweetser risked getting compromised since the reaction of the public, and especially an American audience, to such a letter was hard to predict. The safest way to avoid awkwardness was to make it seem as if the letter had never been in the hands of people from the Secretariat. Sweetser’s wording, when forwarding the letter to the members of the Information Section was telling:

“I have now had permission to use that letter, entirely unofficially and impersonally, and am attaching a copy herewith in case it might be of any use to you. All that could be done, of course, is to send the letter, quite personally, to one or two friends for publication, as a matter of general interest.”[10]

This use of the letter falls under a category of League information work that was referred to as “liaison” in the Secretariat and involved the maintenance of, as the Information Section put it in 1921, “a small body of some hundred carefully chosen persons” in each country, for example “parliamentarians, journalists, members of the government, civil servants, financiers, professors […]”.[11] An underlying assumption was that while the Secretariat could not make propaganda, they could assist private associations, distinguished personas and celebrities in promoting the League by providing information to them.[12] This was pursued through discreet, personal correspondence and consequently there is today no surviving list in the League archives of what persons and associations the Information Section was in contact with.

The constant internationalists

Meanwhile, in the ‘unconstrained end’ of the liaison work, and in clear contrast to the subtle maneuvering of the Information Section, Fosdick was working the public in America, sometimes imbuing the visit at the President’s home with an almost biblical and dramatic atmosphere. In his text to the magazine The Survey – Midmonthly on February 4th Wilson had, according to Fosdick, exclaimed in response to criticism of League idealism: “The world is run by its ideals. Only fools think otherwise.” It seems that in the United States the source of propaganda mattered much more than the tone: Secretariat officials were encouraged to keep a low profile, but Americans living and working in the States like Fosdick could be more openly assertive in their liberal internationalism. One of Fosdick’s final recollections from the visit will be our last note:

"In his earnestness, the tears rolled down his face, and when I pledged him on behalf of the younger generation, that we would carry through to a finish the thing which he had started, he gave way completely. My last impression of him was of a tear-stained face, a set, indomitable jaw, and a faint voice whispering 'God bless you.' With his white hair and gray, lined face, he seemed like a reincarnated Isaiah, crying to his country: ‘Awake, awake, put on thy strength O Zion; put on thy beautiful garments, O Jerusalem!'” […][13]

References:

[1] www.nytimes.com/1972/07/19/archives/raymond-b-fosdick-dies-at-89-headed-rockefeller-foundation-l.html (19.09.2017).

[2] Raymond Fosdick to Arthur Sweetser, February 6

th, 1924, ‘Wilson’s Death’, Box 14, Arthur Sweetser Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington D. C. 3.[3] Ibid.

[4] Raymond Fosdick to Arthur Sweetser, February 6th, 1924, note.

[5] Eduoard Chapnisat to Eric Drummond, May 2nd, 1919, ‘Journal de Genève’, R1332, LONA, Geneva.

[6] Arthur Sweetser to Eric Drummond, February 25th, 1924, ‘Wilson’s Death’, Box 14, Arthur Sweetser Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington D. C.

[7] Arthur Sweetser to Eric Drummond, February 28th, 1924, ‘Wilson’s Death’, Box 14, Arthur Sweetser Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington D. C.

[8] Madeleine Herren and Isabella Löhr, “Gipfeltreffen im Schatten der Weltpolitik: Arthur Sweetser und die Mediendiplomatie des Völkerbunds.” Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft , no. 62, vol. 5, 411-424.

[9] Warren F. Kuehl, Biographical Dictionary of Internationalists, (Greenwood Press: 1983) 266.

[10] Arthur Sweetser to all members of the Information Section, February 28th, 1924, ‘Wilson’s Death’, Box 14, Arthur Sweetser Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington D. C.

[11] Secretariat de la SDN. Commission d'enquéte, C.E.1-27, (Geneve: 1921).

[12] For a general view on Secretariat relations to such associations see Thomas R. Davies, “A ‘Great Experiment’ of the League of Nations Era: International Nongovernmental Organizations, Global Governance, and Democracy Beyond the State”, Global Governance 18 (2012) 405-423, 411; Bertram Pickard, “The Greater League of Nations – A Brief Survey of the Nature and Development of Unofficial International Organizations”, Contemporary Review no. 150 vol. 850 (1936). 460-465, 465.

[13] Clipping of article from The Survey – A Midmonthly February 4th, 1924, ‘Wilson’s Death’, Box 14, Arthur Sweetser Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington D. C.

Images:

Pictures of Raymond Fosdick and Woodrow Wilson are from Wikimedia Commons: commons.wikimedia.org (03.10.17).

Picture of Arthur Sweetser is from the

League of Nations Photo Archive (Indiana University): www.indiana.edu/~league/photos.htm (02.05.17).