The Scandinavian Center: Denmark and the Early Years of International Studies under the League of Nations

Søren Friis (PhD student - Aarhus University)

The Institute of Economics and History (Institutet for Historie og Samfundsøkonomi, IHS) was established in 1927 as an independent, interdisciplinary research institute partly connected to the University of Copenhagen. The initiative was undertaken by a small group under the leadership of P. Munch, a historian and leader of the centrist Social Liberal Party, who served as Danish foreign minister 1929-40 and as a highly active delegate to the League of Nations for nearly twenty years.

The institute in Copenhagen was a small but vital piece in a history recently rediscovered by scholars of the interwar period: The early days of formalized cross-border cooperation among experts and scholars, so-called “intellectual cooperation”. One key development was the interwar International Studies Conference (ISC), which came to encompass a network of “international studies” research institutes (or “think-tanks”) and scholars of various stripes.

The interwar International Studies Conference reflected a multi-layered case of internationalization: It gathered something resembling an international community of scholars not to discuss any pre-defined specialist interest but rather to define what it meant to undertake “international studies” (its objects, aims, methods, etc.). Furthermore, there was a clear desire to influence not only the shape of this would-be discipline but also its very object, a concern largely founded on a “liberal internationalist” outlook that emphasized the importance of institutionalized international cooperation.

There is quite a bit we don’t know about the individual actors and institutions that make up this story of transnational networking and – lest the impression becomes too rosy – conflict. Some scholars have chosen to focus mainly on key Anglo-American institutions and characters, arguing, often convincingly, that these dominated the proceedings. However, if we want to understand the power dynamics within such transnational networks, we should also examine its peripheries, that is, the kind of sites where grand ideas and schemes were translated into local practices. In the following, I take a brief look at a few key developments and changes in the relationship between the Danish IHS and its international network and suggest that they might be explained through the tension between internal and external motivations for the international “networking” carried out by the Copenhagen institute.

Left: The Palais-Royal in Paris, where the IIIC was housed from 1926. Centre: Jurahuset at Studiestræde 34, one of the University of Copenhagen addresses which housed the IHS during its existence. Right: Spanien 65, the first home of the newly founded Department of Economics at Aarhus University from 1936, where a number of IHS economists migrated. Photos: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, Ann Priestley, Søren Friis.Left: The Palais-Royal in Paris, where the IIIC was housed from 1926. Centre: Jurahuset at Studiestræde 34, one of the University of Copenhagen addresses which housed the IHS during its existence. Right: Spanien 65, the first home of the newly founded Department of Economics at Aarhus University from 1936, where a number of IHS economists migrated. Photos: French Ministry of Culture and Communication, Ann Priestley, Søren Friis.

Versailles and the International Affairs Think-Tank

The first step in connecting the Institute of Economics and History to the grand picture could be to ask: What was its purpose? Created in 1927, several of its leading protagonists pressed for cooperation and collaboration within the social sciences and humanities. There was a strong need, they felt, to draw on the natural sciences and their methods: With the enormous wealth of material becoming available, scholars within the humanities (e.g. historians, as several were) could no longer hope to succeed without collaborative efforts and the use of “scientific” methodologies. As such, Munch and his colleagues argued for combining the efforts of historians with the methods of economists and statisticians. The order of the day was interdisciplinary cooperation with a “hard scientific” bent, pursued in order to strengthen the standing of the historical discipline in particular. [1]

Was there anything particularly “international” about the Institute’s objectives? Certainly, the institute was not lacking in foreign inspirations. When its initiators explained why the institute was needed, a new generation of research institutes in cities such as London, Berlin and Paris were all roundly praised. What did these have in common? On a Friday evening some eight years before (30 May 1919), a group of 37 scholars and experts involved in the British and U.S. delegations to the Paris Peace Conference had first met at the Hotel Majestic in Paris. The agenda: How to continue their mutual cooperation after the completion and signing of the Versailles Treaty, which was only a month away. These British-American talks ultimately resulted in the creation of the British Institute of International Affairs, or “Chatham House” after its home in London, and its counterpart, the Council of Foreign Relations in New York.

The two institutions – Chatham House in particular – became blueprints for similar institutions that popped up worldwide in the following two decades. On the European continent, new institutions in places such as Paris, Milan and Warsaw labeled themselves as foreign affairs institutes. In Geneva, the Institut Universitaire de Hautes Etudes Internationales or “Graduate Institute”, established in 1927, organized graduate teaching on international questions with the aid of civil servants of the League of Nations, to which it was closely connected. On top of this came an influential group of research institutes – focusing mainly on economic and social studies – in cities such as Berlin, Kiel, Frankfurt, Vienna and Stockholm. All these were hailed as inspirations for the institute in Copenhagen.

The International Studies Conference (ISC), 1928-1939

In 1928, soon after IHS was established, this new generation of independent “think-tanks” were formally bound together under the League of Nations’ International Institute of Intellectual Cooperation (IIIC). [2] Such an international body had been envisaged since the earliest days of the League, but only materialized in 1926 after much haggling – in its final design, the institute was to be headquartered in Paris and led by a Frenchman. The venue for the cooperation of this diverse network of “Institutes for the Scientific Study of International Relations” finally came to be known as the International Studies Conference. The ISC agenda was ambitious and wide-ranging, covering general issues such as economic crises, rearmament within Europe, nationalist expansion, imperial conflict, and ultimately, the looming specter of unavoidable war within Europe.

The annual conferences drew a varied crowd of scholars, League officials and agents of key philanthropic foundations (Rockefeller Foundation and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace). The first conference was organized by Berlin’s Hochschule für Politik in 1928, which instituted a tradition of yearly plenary sessions hosted by research institutes on turn. The last session, in Bergen, was held only weeks before the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. After 1931, where the Copenhagen institute played host, the ISC took on a more permanent character and it was decided to pursue biennial “study cycles” devoted to specific topics of common interest. The 1932-33 cycle was devoted to “The State and Economic Life” (Milan and London); 1934-35 to “Collective Security” (Paris and London); 1936-37 to “Peaceful Change” (Madrid and Paris); and finally, 1938-39 to “Economic Policies in Relation to World Peace” (Prague and Bergen). [3]

Copenhagen and the ISC

In March 1929, the Institute of Economics and History was first represented – by the economists Bertil Ohlin and Jørgen Pedersen – at the second annual conference in London. Extending from this meeting, it crossed the Atlantic and entered into cooperation with the U.S. Social Science Research Council (as the Scandinavian contributor to its world-wide bibliography on the social sciences) and the Council on Foreign Relations (contributing to its quarterly bibliography on international relations in the journal Foreign Affairs). From then on, it participated annually within the ISC framework, represented by a number of scholars, perhaps most notably the economists Jørgen Pedersen and Carl Iversen, both driving forces in facilitating the new international connections of the Danish Institute.

This was a turning point. Indeed, there was nothing very “international” about the research carried out at the Danish institute prior to the early 1930s. Its early research projects, formally divided between two separate sections comprising the historians and economists in residence (senior researchers were university-employed professors and lecturers; graduate students worked at the institute for free), consisted mainly of historical studies of social and economic developments in Denmark. The institute’s quarterly journal Økonomi og Politik, however, did take a continuing interest in international politics and the world economy.

Despite the keen international interests and early pronouncements of Munch and other colleagues, it seems that no written study with an international or foreign focus was undertaken at IHS during its earliest years. In 1930, this changed as IHS, on Munch’s request, set up a new study group in international post-war history with offset in the Paris Peace Conference. This was the Institute’s fourth such study group (previous groups having dealt with domestic historical issues) and it would remain active for several years. It led to an increasing number of study groups and published studies on such diverse issues as colonial problems, issues of international trade, contemporary German foreign policy and Franco-Italian relations.

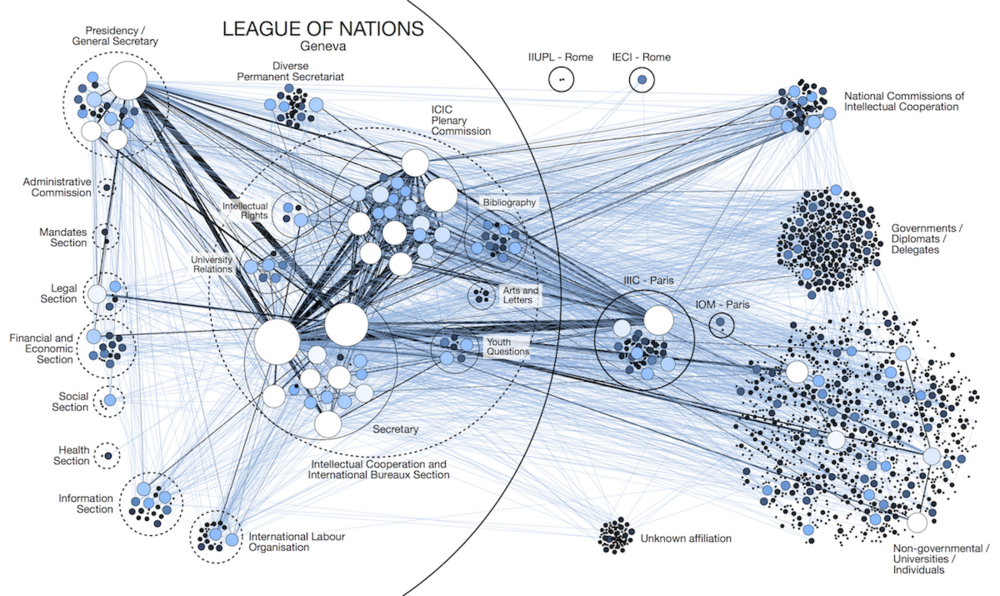

Network analysis of the League of Nations’ organization centering the bodies involved in intellectual cooperation (1919-27) and visualizing the complex relationship between League bodies and outside institutions. Source: Martin Grandjean (http://www.martingrandjean.ch/intellectual-cooperation-multi-level-network-analysis/)Network analysis of the League of Nations’ organization centering the bodies involved in intellectual cooperation (1919-27) and visualizing the complex relationship between League bodies and outside institutions. Source: Martin Grandjean (http://www.martingrandjean.ch/intellectual-cooperation-multi-level-network-analysis/)

An International Affair?

By the turn of the decade, then, what began not as an “institute of international affairs” strictly following the Anglo-American model was perhaps in the process of becoming one. A factor in this part-way transformation was the institute’s main transatlantic funder: The Rockefeller Foundation – which also funded several other think-tanks in Europe as well the ISC meetings [4] – became the largest contributor to the Copenhagen institute already by its second year. In fact, its initial promise of funding seems to have a necessary condition for the institute’s creation.

With the creation of the International Studies Conference as the new framework for international cooperation in this field soon after, the Rockefeller Foundation’s aims in supporting the Copenhagen institute shifted somewhat. Initially supportive of the institute’s academic mission of strengthening the state of interdisciplinary work within the social sciences, an aim very much in line with the Foundation’s own at this point, reports by the Foundation during the 1930s began to tout the Copenhagen institute as a particularly successful node – a Nordic bastion of sorts – in its network of international affairs institutes in Europe. “[T]he Danish Institute,” argued the Rockefeller Foundation in 1938, “led the Scandinavian countries in creating a center of interest in international relations, and served as the model for the centers set up by Norway and Sweden.” [5]

For its American funders, then, the value of the institute in Copenhagen was strongly tied to its role (largely an imagined one) as the center of a Scandinavian group of foreign affairs think-tank. In fact, IHS’ own annual reports make it clear that the first small steps toward Nordic cooperation in the field of international studies were only undertaken in 1938-39 before being halted by the war. This suggest that the demands of the ISC (and Rockefeller) network played a large role in bringing this cooperation about. That is, Nordic cooperation in this field was not only driven by organic ideological commonalities, such as the arguable “peace tradition” shared by the countries in question, but also by external attempts to imagine such a coherent Nordic tradition and the role it might play in furthering liberal internationalist aims.

These motivations sometimes led to some curious discrepancies in perception, such as when Rockefeller claimed to be funding an “International Relations Section” at IHS, whereas the institute itself did not make any mention of such a section in any of its annual reports. This suggests a situation where the institute in Copenhagen did not have much of a stake in its expected role as “the chief Scandinavian center for scientific interest in international relations”, as it were in the Rockefeller imagination [5], yet it was certainly motivated to meet such expectations.

By the late 1930s, IHS was able to credibly report on a host of activities encompassing both the study of a range of international problems and the formalized cooperation with other institutes in Scandinavia and beyond. Parallel to its ISC activities, the Institute also participated in a series of key meetings of select economists co-initiated by the League of Nations’ Economic and Financial Organization and the Rockefeller Foundation, forging ties to a network of liberal (and early neoliberal) economists and intellectuals (see note 1).

Postscript: A New Era

Despite efforts to revive its activities after the war, the International Studies Conference did not survive the creation of UNESCO, under which the newly created International Political Science Association (IPSA) superseded it as the official international forum for cooperation in the field of international studies. [7] By the early 1950s, International Relations (IR) had formally become the domain of political scientists rather than of the diverse group of historians, economists, sociologists, classicists, philosophers and others who took part in its shaping during the interwar years. Similarly, the Copenhagen institute – financially weakened after the loss of Rockefeller funding – became something of an anachronism at the University of Copenhagen, where its own leadership engineered its division into separate departments for history, economics and political science by the late 1950s.

The career trajectories of some of IHS’ pre-war alumni illustrate that the legacies of the economists somewhat overshadowed those of the historians: Jørgen Pedersen, who had managed the institute’s daily activities in its first decade, became professor at the newly established Aarhus University in 1936, where he presided over the creation of the Department of Economics. Carl Iversen, who had also been a representative to the ISC and other international fora, would serve as both professor of economics and rector of the University of Copenhagen, as a UN advisor on economic development, and later as the first chairman of the Danish Economics Council (“overvismand”). Another participant, Thorkil Kristensen, went on to become professor of economics in Aarhus, minister of finance (Liberal Party), and the first secretary-general of the OECD (1960-69).

Under the League of Nations, the social sciences and humanities had jointly experienced a flowering of cross-border cooperation, as significant new venues for scholarly cooperation emerged. As the United Nations and a host of new international organizations emerged, a more streamlined brand of social science expert-advisor took over, and many of the surviving “institutes of international affairs”, not least its original flagships in New York and London, were well-situated to meet these demands – with their assemblages of expertise covering newly prominent Cold War fields such as international relations, area studies and development economics.

Decades after the Institute of Economics and History had shut its doors, the model of the international affairs institute born at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 was still being re-adapted worldwide: Its own Danish forerunner long forgotten, yet still consciously modelled on the sister institutes in Stockholm (UI) and Oslo (NUPI) that had outlived it by far, the first “proper” Danish Institute for International Studies would finally see the light of day in 2003, set up by political decree as an “independent research institution for international studies” financed by the Danish state.

References:

[1] Søren Friis (2016) “Social Science Diplomacy: Dimensions of Transnational Networking at Denmark’s First International Studies Think-Tank”. Working paper presented at the APH 4th International PhD Conference, Aarhus University, June 2016.

[2] Daniel Laqua (2011) “Transnational intellectual cooperation, the League of Nations, and the problem of order”, in Journal of Global History 6, 223-47.

[3] Michael Riemens (2011) “International academic cooperation on international relations in the interwar period: the International Studies Conference”, in Review of International Studies, 37 (2), 911-28.

[4] Katharina Rietzler (2011) “Experts for Peace: Structures and Motivations of Philanthropic Internationalism in the Interwar Years”, in Daniel Laqua (ed.) Internationalism Reconfigured: Transnational Ideas and Movements between the World Wars, 45-65. London: I.B. Tauris.

[5] The Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report 1938, p. 264.

[6] The Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report 1936, p. 249. Annual financial statements in Årbog for Københavns Universitet (Yearbook of the University of Copenhagen) and reports by IHS in Økonomi og Politik, vols. 1-34, were also consulted.

[7] David Long (2006) “Who killed the International Studies Conference?”, in Review of International Studies, 32 (4), 603-22.