“The League is dead, long live the United Nations” – The Liquidation of the League and the transfer of assets to the UN

Torsten Kahlert (postdoc – Aarhus University)

When did the League of Nations cease to exist? Was it with the United Nations Conference on International Organization in San Francisco, where the League leadership were “guests at their own funeral”[1], or perhaps with the League’s final Assembly in April 1946? Not quite.

This blog narrates the final, irrevocable end of the League: the physical liquidation and the transfer of its material assets and properties to the United Nations. As will be argued, the negotiations between the League of Nations and the United Nations were neither a neutral process of “handing over” assets to the UN, as one League publication suggested[2], nor was there really a neat distinction between the two negotiating parties. Rather, the League’s liquidation demonstrates clearly two matters: First, that the UN sought to distance itself from the League, to avoid being tainted by its hew of failure, while the League sought to retain a minimum of dignity. Second, that the UN officials negotiating the League’s final act where overwhelmingly old League officials. Thus, the liquidation of the League was its last administrative act, with League officials active on both sides, as a reminder that International Organizations rarely cease to exist - they only change form.

Seán Lester (1888-1959), Secretary General from 1940-1946

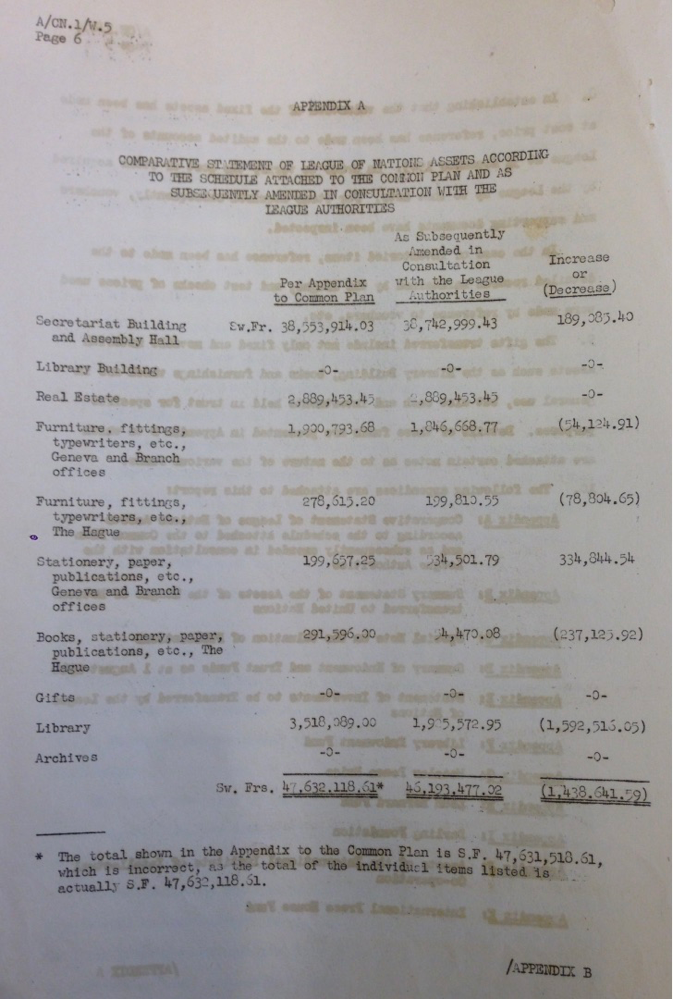

When visiting the League Archives in Geneva, searching for information about the careers of the Secretariats personnel after the dissolution of the international organisation, I came across a pile of documents concerning the transition phase of 1946/47 and the transfer of the League of Nations’ property to the newly founded United Nations. The documents list the properties of the League of Nations (the Palais des Nations being the main estate), the furniture, the typewriters, the publications, the library and the funds the League owned, and contains detailed correspondence on how to estimate the value of these assets, These records document the final administrative efforts for the transition of the League of Nations to the UN, the involved actors and the procedure of handing over what remained of the League and its Secretariat by the end of the war.

Dissolution and Liquidation

For a short period of time, the League of Nations and the United Nations existed side by side. In June 1945, the Charter of the United Nations was adopted, which is generally seen as the birth of the United Nations. The UN position was developed in the Preparatory Commission, which had representatives of all 51 UN member states and held its meetings in London in the second half of 1945. In February 1946, the UN held its first General Assembly in London. Part of the agenda was how to deal with the League of Nations, especially the transfer of functions, property and assets. All such matters were gathered in the so called “Common Plan”, which had been negotiated and worked out by the Supervisory Commission of the League and the United Nations Committee and approved by the General Assemblies of both organisations. Apart from officially confirming the dissolution of the League of Nations, the Common Plan stipulated a mutual agreement on the transfer of material assets.[3]

Negotiations on which assets to transfer, which to sell, and which to turn back to original owners, took place in March 1946 (before the last Assembly of the League of Nations, which approved the Common Plan and its formal dissolution). With this settled, the UN Geneva office, the Liquidation Board of the League of Nations and the remaining staff around Seán Lester dealt with the valuation of the assets, property, publications (e.g. the treaty series and the library) and the different funds, the League owned, from April 1946 to July 1947.

All in all, a machinery of six main bodies and certain commissions and committees were involved in the transfer and liquidation process. Besides the already mentioned commissions and committees, the Board of Liquidation – consisting of nine League representatives, from Bolivia, China, Czechoslovakia, France, India, Norway, South Africa, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, respectively – was responsible for the formal liquidation. In Geneva, the UN operated with a Secretariat, the UN Geneva office, which transmitted the reports and agreements to the respective organs of the United Nations.[4]

Palais des Nations, 3.4.1939

To get an oversight, the UN officials needed inside information. Accordingly, former League official and current UN official Egon Ranshofen-Wertheimer, was sent to Geneva to write a lengthy report on possible functions and assets to be transferred. The UN nominated a so-called Negotiating Committee to deal with questions of property with the Swiss authorities, especially the Palais des Nations and the grounds on which it was standing, the Ariana Park, and the private houses of the Secretary General and other high officials.

The property was divided into three classes: assets which the League acquired by purchase; assets which were acquired as gifts and; assets of gifts, to which no cost value had been assigned. From the total sum of around 47,5 Million Swiss Francs, 38,5 Million Swiss Francs were the buildings (approximately 93 Million Euros today). The second biggest item was the library, followed by furniture, typewriters, books and paper and so on. With this, the League was no more.

Signing of an agreement on the transfer of certain assets. Seán Lester at the end of the table and Moderow to the right with the dark glasses.

Disrespect and Dignity

There is general agreement among historians that the United Nations had no interest in being seen as the successor of the League. At the same time, however, the UN was keenly interested in acquiring the physical remnants of the League. The last League officials on their side, it seems, were interested in retaining the organisations dignity and to be treated as on par with UN officials. As the following anecdote indicates, however, the liquidation was not always amicable.

Part of the valuation of properties and assets were inspection tours through the buildings of the League. Seán Lester was surprised by UN officials during one of these inspection on April 10, 1946. The officials informed him that they wanted to inspect “the grounds of La Pelouse and the house itself” – his private home and grounds. Bemused by the surprise visit, Lester decided to let them visit the grounds, but refused access to his private residence “on such short notice”, as he wrote to Wlodzimierz Moderow, Chairman of the UN Negotiating Committee and the highest-ranking UN official in Geneva (he later became the first director of the European Office of the United Nations). Moderow replied that Lester’s Director of Personnel and Internal Administration, Valentin Stencek, had been notified on April 9th, but added that the “inspection tour [was] completed” anyway, and that they would “certainly not disturb [him] at [his] private residence during the few hours of rest which [he] enjoy[ed] at present.”[5]

This short anecdote tells us a lot about the relationship between the new and the old organisation. Instead of respectfully apologising for the short notification and the disturbance, Moderow simply referred to bureaucratic procedures, claiming that one day’s notice was enough. The scene is illustrative of the League’s dwindling importance, but perhaps even more so, Lester’s marginalised role in international politics by the end of the war. One cannot help but read a bit of sarcasm into the last sentence, though this might not have been the intent. Certainly, if all Lester had to do was to hand over the remains of the League, then he should have nothing but time for inspections. Lester’s firm but futile stance, moreover, captures his attempt, perhaps also on behalf of the League as such, to retain control and dignity to the very last.

Though the example above implies a passive League responding to the demands of a new and potent world organisation, Moderow, and the UN more generally, were very much dependant on the League officials to finalise the liquidation.

League of Nations Turns Over Historic Documents to United Nations (left Moderow, middle Lester)

The League on Both Sides

In fact, League officials and former League officials were prevalent on both sides of the table, as the final act of the organisation played out.

In July 1946, Moderow sent an expert to Geneva, in order to evaluate the lists of properties prepared by the League itself, and to verify their estimated value. Zdenek Smetacek, as the expert was called, stayed in Geneva evaluating the lists of properties and prices for almost a month. In a joint meeting between League and UN staff, the procedure was laid out, and it was decided that his examination should be limited to the verification of “furniture, fittings, typewriters etc., and stocks of stationary, printing paper, office supplies and equipment.” He concluded that all items were listed “as correct as they may be expected to be in the circumstances and can be relied upon in determining the valuation of items transferred to the United Nations by the League of Nations on August 1st, 1946.”[6] Though the procedure clearly indicates an asymmetric relationship between the two organisations (explored above) – one doing the grunt work, the other supervising – it also shows how League officials were instrumental in settling the estates.

Appendix A of the report on the final valuation of the assets of the League of Nations

On the UN side, moreover, there were at least four former officials of the League Secretariat involved: Moderow himself, a lawyer by training with a background in Polish administration, had worked for the League’s Permanent Committee for Transit and Communication. Adrian Pelt, the assistant of UN Secretary General Trygve Lie and deeply involved in the transfer and liquidation, had worked for the League Secretariat for twenty years, first as a member (1920) and then as head (1934) of the Information Section. Egon Ranshofen-Wertheimer, assisting the UN as an expert of the structure and functioning of the Leagues Secretariat, had since 1930 worked in three different sections of the League Secretariat. Last, Thanassis Aghnides, who had worked in the League Secretariat from 1920 to 1942 rising to the position of Under Secretary-General [7], functioned as Rapporteur of the report on the transfer of assets of the Fifth Committee of the UN in December 1946.

“The League is dead, long live the United Nations”

Though Robert Cecil famously proclaimed “The League is dead, long live the United Nations” in his opening speech at the last Assembly of the League, April 1946, this was not entirely true. The remaining officials still had to show the administrative abilities of the League’s one last time. More significantly, it was former League officials that drove the process of liquidation on the UN side. This might indicate a wish on the former League officials’ part to send the organization off in a dignified way, but was more likely a question of competence. The UN depended on the know-how and contacts of former League officials to shut down its predecessor – another chapter in the story of the interwovenness of the two world organisations.

The closing event of the last chapter of the League of Nations was a cocktail party, held for the remaining League officials and the staff of the UN Geneva headquarters. It was more expensive than expected. The new organisation had to pick up the tab for the old one.[8]

References:

[1] Patricia Clavin, Securing the World Economy: The Reinvention of the League of Nations, 1920-1946 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 341.

[2] League of Nations, The League Hands over (Geneva, 1946).

[3] General Report of the Finance Committee to the Assembly (Second Committee), Twenty-first ordinary Session of the Assembly, Geneva 18th April 1946, p. 12.

[4] With more details on the procedure and the different commissions involved: Denys P. Myers, “Liquidation of League of Nations Functions,” The American Journal of International Law 42, no. 2 (1948): 320–54.

[5] LONA, G I, 4/1 (23): Transfer Assets, Function and Staff.

[6] LONA, G1, 4/4 (26): “Report by Zdenek Smetacek, 8 August 1946” in Transfer of Assets, Functions and Staff. Valuations of Assets.

[8] LONA, G1, 4: Cocktail Party on termination of League activities.

Images:

Seán Lester: http://www.indiana.edu/~librcsd/nt/db.cgi?db=ig&do=search_results&details=2&ID=936&ID-opt==, accessed November 20 2017.

Palais des Nations:

ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv/Stiftung Luftbild Schweiz /Fotograf: Friedli, Werner / LBS_MH01-008444 / Public Domain Mark, accessed November 20 2017, doi.org/10.3932/ethz-a-000300259.

All other pictures are from the United Nations office at Geneva and the League of Nations Photo Archive, Geneva.