The Åland Islands Question – A League Success Story

Eric Hayes (EU Ambassador to Finland 1993-95)

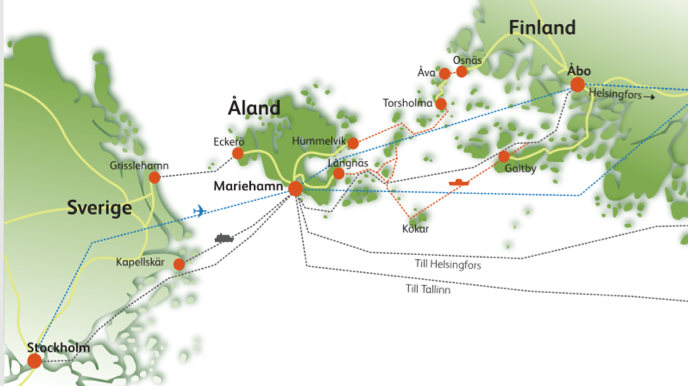

One of the many rewarding, but also daunting, aspects of life as a professional diplomat is the knowledge that you are, in your own small way, contributing to the making of history; and that the issues you deal with are themselves the product of history, shaped by actions or decisions taken decades – or, in some instances, centuries – ago by earlier generations of statesmen and diplomats. One such example from my own career is the Åland Islands question. The peaceful settlement, in June 1921, of the dispute between Sweden and Finland over possession of the Islands (lying mid-way between the two countries, at the entrance to the Gulf of Bothnia) was one of the rare success stories of the League of Nations. I first came across it when drafting, seven decades later, the European Commission’s Opinion on Finland’s application for EU membership.[1] My fascination with Åland has endured, in both my professional and my private life. The imprint of the League’s resolution of 1921 can still be seen today, not only in the constitution of the Republic of Finland, but also, thanks to Finland’s accession, in the EU Treaties.

The Åland Islands

Historical Background

The Åland Islands were, for many centuries, together with mainland Finland, part of the Kingdom of Sweden. In 1809, however, following her defeat during the Napoleonic Wars, Sweden was forced to cede Finland to Russia. The Åland Islands, along with the rest of Finland, became an autonomous Grand Duchy of the Russian Empire, with the Tsar as Grand Duke.

As a result, Åland came to occupy a strategic position as the westernmost point of the Russian Empire; and plans were immediately laid to build a heavily fortified naval base at Bomarsund, on the eastern side of mainland Åland. During the Crimean War of 1854-56, the fortress was captured and demolished by Anglo-French forces. By a Convention annexed to the 1856 Treaty of Paris[2], Russia undertook not to fortify the Islands, nor to maintain or create on them any military or naval establishment (the so-called “Åland Islands servitude”). Sweden, which had remained neutral during the war, was in practice the principal beneficiary of this, and was consequently much alarmed when Russia proceeded, during the First World War, with the tacit consent of Britain and France, to fortify the Islands.

Memorial on Kumlinge to the Ålanders ’struggle against Russia in 1808

(photographed by the author, September 2014)

Following Finland’s declaration of independence in December 1917, in the wake of the October Revolution in Russia, there were growing domestic pressures for Sweden to annex the Åland Islands, whose Swedish-speaking inhabitants, freed of Russian rule, were pressing strongly for reunion with their former mother country. When, in late January 1918, Finland descended into civil war,the Ålanders appealed to Sweden for help and protection from the resulting chaos, confusion and terror. Stockholm responded by sending, ostensibly for humanitarian purposes, a naval expedition to the Islands. Although Swedish forces were withdrawn a few weeks later, the episode left much bad feeling between the Finnish Government and Stockholm. Relations were further strained when the Ålanders, in March, issued a simultaneous appeal to the Finnish Parliament, the Kaiser and King Gustav of Sweden, invoking the right of national self-determination in defence of their reunion with Sweden.

Remains of demolished fortifications on Åland (photographed by the author, August 2003)

The Dispute is Referred to the League

Following the Armistice of November 1918, Stockholm sought to have the Åland question taken up at the Paris Peace Conference where, it was hoped, the much-vaunted principle of self-determination would help ensure a settlement in Sweden’s favour. But the Allies were reluctant to address this thorny and difficult question, and successive reasons were found for postponing discussion. By the beginning of 1920 it was clear that the question would not be addressed by the Peace Conference. Efforts to reach a mutually satisfactory bilateral settlement, as repeatedly urged by London and Paris, were equally unsuccessful. The respective positions of the two sides were irreconcilable: Stockholm insisting on respect for the wishes of the Ålanders; Helsinki insisting that Åland was a purely internal Finnish matter and refusing to agree to a binding plebiscite involving only a fraction of Finland’s Swedish-speaking population.

London urged Sweden to refer the question to the newly-established League of Nations. But the Swedish Government was unwilling to do so for fear of losing face domestically. Finally, amid growing fears that the Ålanders might take matters into their own hands by unilaterally declaring union with Sweden, London concluded, reluctantly, that action was now called for. With the agreement of Paris, British Foreign Secretary Lord Curzon wrote, on 19 June 1920, to Sir Eric Drummond, Secretary-General of the League, invoking Britain’s “friendly right”, under the League’s Covenant, to bring the Council’s attention to the Åland question “as a matter affecting international relations which threatens to disturb international peace”.[3]

When the question came before the Council of the League on 9 July, the Finnish delegation protested that the situation between the Ålanders and Helsinki was of a purely domestic nature, and thus outside the League’s competence. These arguments were, however, rejected by the Council, on the advice of a commission of three eminent international jurists appointed to examine the Finnish claim. The jurists also concluded that the 1856 Convention regarding the demilitarisation of the Åland Islands was still operative and that it was binding on whichever state found itself in possession of the archipelago.[4] Having settled the issue of competence, the Council decided, at its meeting of 20 September, to establish a Commission of Rapporteurs “to present to the Council the necessary factors on which it might base a recommendation for the settlement of the dispute”.[5] This provoked further Finnish protests [6], causing such alarm in London and Paris that neither was willing to serve on the Commission, despite having been instrumental in its establishment.[7] It was finally made up of Belgium’s former Foreign Minister, a former President of the Swiss Confederation and a former US Ambassador to Turkey, currently serving on the Court of Appeals of New York State.

The big four - Lloyd George (Britain), Orlando (Italy), Clemenceau (France), Wilson (US) - found it quite difficult to put the abstract concept of self-determination into practice.

The League’s Conclusions

After several months of fact-finding and deliberation, the Rapporteurs delivered their report to the Council on 16 April 1921.[8] Their conclusion was that Finland’s right of sovereignty over the Åland Islands was “incontestable”; and that their present legal status was that they formed a part of the Finnish state. There was, in their view, no case for applying the doctrine of self-determination, since there was no reason to doubt the willingness of the Finnish state to grant the Ålanders satisfactory guarantees. They recognised, however, that the Åland population had a legitimate fear “of being little by little submerged by the Finnish invasion” and consequently recommended the concession by Helsinki of certain additional guarantees to ensure the preservation of the language, culture and way of life of the Islanders.

After some difficult and heated discussions in the margins, masterminded by Britain and France, the Council, on 24 June 1921[9], approved a resolution, drafted by Britain, confirming Finnish sovereignty over the Åland Islands, subject to the granting by Helsinki of further guarantees in the areas identified by the Commission of Rapporteurs. The precise details of these were to be negotiated between Sweden and Finland, with the assistance of a representative of the Council. This was accepted, under strong protest, by the Swedish delegation. On the security aspect, the 1856 Convention was to be replaced by a broader international agreement for the neutralisation of the Islands, along the lines of an earlier Swedish draft.

The result of these bilateral negotiations was presented to, and approved by, the Council at its session of 27 June and annexed to the earlier resolution of 24 June.[10] The terms of agreement covered:

· the language of tuition in schools and other educational establishments;

· restrictions on the purchase of property in the Islands by other than legally domiciled Ålanders;

· restrictions on the acquisition of communal and provincial voting rights by Finnish citizens moving to the Islands;

· the procedure for the nomination by the President of the Republic of future Governors of Åland;

· the share of tax revenues to be retained by the Åland Provincial Government.

These additional guarantees were to be introduced at an early date into the Law of Autonomy that had been enacted by the Finnish Parliament the previous year, and the Council of the League was to “watch over” their application.

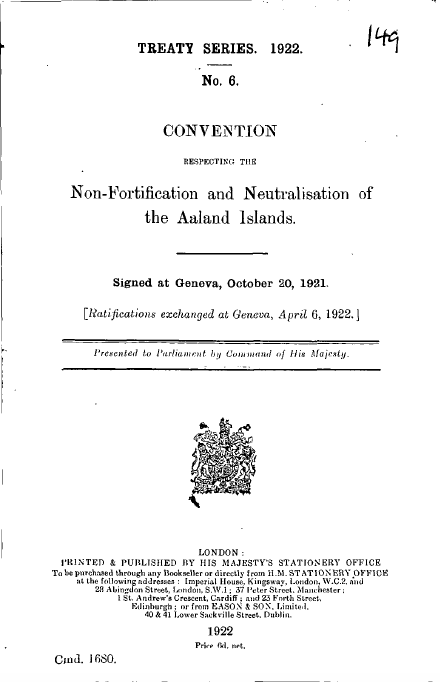

Convention on the Non-fortification and Neutralisation of the Åland Islands

The final piece in the jigsaw was the signature, on 20 October 1921, of the Convention on the Non-fortification and Neutralisation of the Åland Islands.[11] Signatories to the Convention were the states bordering on the Baltic (with the exception of Russia and Lithuania), together with Britain, France and Italy. Under it, Finland committed herself to respect the obligation, undertaken by Russia in the 1856 Convention, not to fortify the Islands. The existing restrictions on the maintenance or establishment on the Islands of any military or naval installations were extended to cover any “installation utilisée à des fins de guerre”. Stringent limitations were imposed on any military, naval or air force presence in the archipelago. In the event of war, the archipelago was to be regarded as a neutral zone, not to be used, directly or indirectly, for any military purpose. The Council of the League of Nations was charged with ensuring the effective application of these provisions.

Life after the League

Although Russia remained outside the 1921 Convention, the latter’s demilitarisation provisions (although not those relating to neutralisation) were replicated in the Finno-Soviet treaty concerning the Åland Islands of 11 October 1940[12], concluded at the end of the Winter War. Furthermore, the 1947 Peace Treaty[13], concluded between Finland, Britain and the USSR at the end of World War II, provided (Article 5) that “the Åland Islands shall remain demilitarised in accordance with the situation as at present existing”. All these provisions are generally accepted as still being in force today, as are those of the 1921 Convention (despite the termination, upon the demise of the League of Nations, of the related international guarantee) and, possibly, even those of the 1856 Convention.

The Law on Autonomy, meanwhile, has been substantially updated and extended twice: in 1951 and in 1993. Under the current Autonomy Act, the Åland Lagting has exclusive legislative competence in areas relating to the internal affairs of the region, such as education and culture, health and medical services, promotion of business and industry, internal communications and local taxation. Any amendment of the Autonomy Act has to follow the special legislative procedure for constitutional amendments and requires in addition the consent of the Åland Lagting. The Finnish Government is thus, in effect, constitutionally bound to respect, even today, the terms of the League’s resolution of June 1921.

Seat of the Åland Autonomous Authorities, Mariehamn

The provisions of the Åland Autonomy Act, as I was to discover in 1992, and subsequently as EU Ambassador to Finland, posed special problems in relation to Finland’s application for EU membership, since certain of these provisions were incompatible with the EU’s Single Market acquis[14], to which Finland, as a Member State, would be obliged to adhere. Furthermore,the consent of the Åland Lagting was required before any international agreement affecting areas of autonomous competence could enter into force for Åland. The Finnish Government was consequently obliged, during the accession negotiations, to seek, on Åland’s behalf, derogations relating notably to the right of establishment, the freedom to provide services and the ownership of property. A derogation was also negotiated in the field of indirect taxation to permit the continuation, on travel to and from Åland, of the sale of duty-free goods. This was not a direct consequence either of the 1921 resolution or of the Autonomy Act, but certainly reflected the spirit of the former. Duty-free sales are a significant contributor to the profitability of the ferry services to the mainland on which the viability of the Åland economy is highly dependent. These various derogations are enshrined in the EU acquis[15] by virtue of a special Protocol to the Treaty of Accession of 1994.[16]

One of the many Åland-owned ferries serving the Islands

The question of Åland’s demilitarisation and neutralisation was initially a source of concern to some on the EU side, as was Finland’s neutrality in general; and was, for that reason, referred to in the Commission’s Opinion. By the time accession negotiations were concluded, however, the geo-political environment had radically evolved, and the issue was not touched upon in the Treaty of Accession. It is significant nevertheless that, since 2004, all ten original signatories to the 1921 Convention are now Member States of the EU.

References

[1] Commission Opinion on Finland’s Application for Membership, Bulletin of the European Communities, Supplement 6/92, p. 24.

[2] Reproduced in Wahlberg (1993).

[3] Covenant of the League of Nations, Article 11 (http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/leagcov.asp).

[4] Report of the International Committee of Jurists, League of Nations Official Journal, Special Supplement no. 3, October 1920.

[5] League of Nations, Council, Minutes of the Ninth Session of the Council of the League of Nations Held in Paris, September 16-20, 1920.

[6] League of Nations, Official Journal, 2 (Jan-Feb 1921), p. 78.

[7] Conclusions of Cabinet meeting of 30 September 1920 (National Archives, CAB 23/22/15).

[8] League of Nations, Council doc. B 7 21/68/106, 16 April 1921.

[9] Minutes of the Fourteenth Meeting of the Council(League of Nations – Official Journal, September 1921, pp. 697-700).

[10] Minutes of the Seventeenth Meeting of the Council(League of Nations – Official Journal, September 1921, p.701).

[11] Reproduced in Wahlberg (1993)

[12] Reproduced in Wahlberg (1993)

[13] Reproduced in Wahlberg (1993)

[14] The body of law constituted by the EU treaties, secondary legislation and legal jurisprudence.

[15] Currently in Article 355(4) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

[16] Protocol No. 2 on the Åland Islands, Official Journal of the European Communities C251, 29.08.94, p. 352.

Literature

Barros, J. (1968). The Aland Islands Question: Its Settlement by the League of Nations.Yale University Press.

Greenhill, B., & Giffard, A. (1988). The British Assault on Finland 1854-1855: A Forgotten Naval War.London: Conway Maritime Press.

Hayes, E. (2011). Aland Aspirations - and EU Anxieties, in From Cold War to Common Currency: a personal perspective on Finland and the EU.Helsinki: Finnish Institute of International Affairs - Foreign Policy Papers No. 1., Ch. VIII (pp.57-65)

Rosas, A. (1997). The Åland Islands as a Demilitarised and Neutralised Zone. In L. Hannikainen, & F. Horn (Eds.), Autonomy and Demilitarisation in International Law: Aland Islands in a Changing Europe.Brill.

Wahlberg, P. (Ed.). (1993). International Treaties and Documents Concerning Åland Islands.Mariehamn: Ålands Kulturstiftelse.

Images:

1) www.visitaland.com (03.05.2018).

2) Photographed by the author, September 2014.

3) Photographed by the author, August 2003.

4) Council of Four at the WWI Paris peace conference, May 27, 1919, taken by Edward N. Jackson (US Army Signal Corps). Courtesy of https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Big_four.jpg (03.05.2018)

6) www.aland.ax/fakta/sjalvstyrelsen (03.05.2018)

7) Courtesy of Viking Lines - https://www.vikingline.com/en/press-room/image-bank/ships (03.05.2018)