Multiple Internationalisms at the League of Nations Secretariat, 1933-1940

Marco Moraes (PhD Student - University of Oxford)

The secretariat of the League of Nations was founded in 1919 as the first fully international civil service in history. Just what that ‘international’ meant, however, remained a source of tension throughout its existence. One area which highlights the multiplicity of internationalisms in the interwar period is the 1933-1940 administration of the League’s second Secretary-General, Joseph Avenol. Most of the existing literature assesses Avenol as an inept and misconceived official, an arch-appeaser who undermined the League’s principles.[1] However, if we assess his political actions alongside his administrative measures and in light of recent studies of alternative internationalisms at the time, particularly fascist internationalism, we can paint a much more complex, and darker, picture of the practice of internationalism then. It reminds us that there is not just one interpretation of ‘internationalism’, and that international organisation can take many forms – a valuable lesson for today.

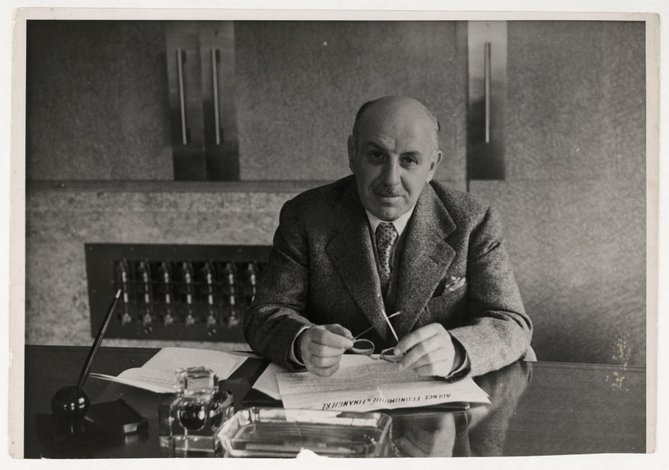

Joseph Avenol, remembered mostly for his betrayal of the League, was much more than merely an inept official.

Before Avenol

The League’s first Secretary-General, Eric Drummond, outlined the international civil service model at the Paris peace conference [2], and reaffirmed it in memos to the League’s Preparatory Commission in 1919 [3] and the Council in 1920: “[t]he Members of the Secretariat act, during their period of office, in an international capacity, and are not in any way representatives of their own country” [4]. This became an institutional principle through the 1920 Balfour Report[5] and the 1921 Noblemaire Report[6], subsequently adopted into the League’s first Staff Regulations[7] (still appearing in its final edition[8]). As Ole Jacob Sending put it, “[t]he Secretariat was to represent and manage the international as a space distinct from the sum total of member states’ interests, this distinctiveness being anchored in rules established to regulate state interaction”.[9]

From the start, this was a source of debate. During the Drummond administration (1919-1933), the tension peaked in the 1930 Report of the Committee of Thirteen[10], when a small but vocal minority, led by Germany and Italy, argued that “[s]o long as there is no Super-State, and therefore no ‘international man’, an international spirit can only be assured through the cooperation of men of different nationalities who represent the public opinion of their respective nationalities”.[11] In practice, too, the secretariat had often been divided over the meaning of internationalism: for all his creative efforts, Drummond was always concerned with ensuring that his office’s initiative did not stray too far from the Council. Early on, Jean Monnet had criticized this tendency of Drummond’s[12], and the head of the Mandates Section, William Rappard, complained that Drummond was too worried about keeping the British and the French happy, instead arguing that the Covenant provided enough authority for the secretariat to act on its own initiative[13]. Despite his caution, however, Drummond ultimately did not strongly curtail his more independent officials – Avenol’s approach would be very different.

Joseph Avenol, Secretary-General (1933-1940)

Avenol was initially seen as an apolitical technocrat. A French economist, he had succeeded Monnet as Drummond’s deputy and was recognised as an able administrator if an inept political operative. That Avenol was neither interested nor well-informed about politics was no secret: he believed international organisation should be a technical-socio-economic affair, without independent political initiative.[14]

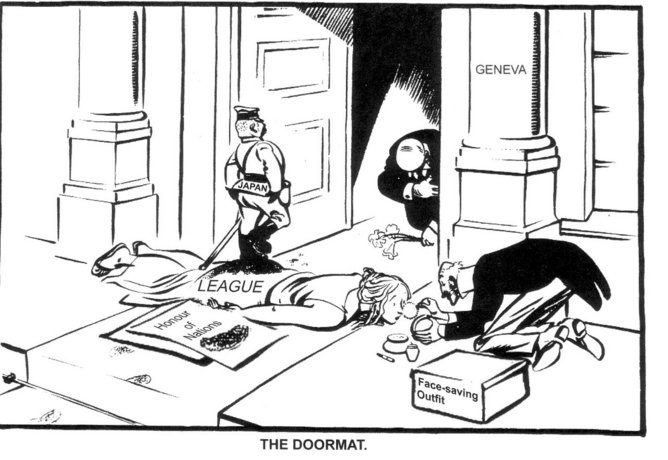

As Secretary-General, Avenol quickly showed that his ‘apolitical’ stance was anything but. In the key crises of the 1930s, his ostensibly technical focus belied a marked political stance. In Manchuria, he immediately decreased the League’s diplomatic activities, even pressuring the more technical sections to avoid any work that might upset Japan. In Ethiopia, it gradually became clear he was using behind-the-scenes negotiations to obtain confidential information for Italy rather than as an impartial mediator [15] - by summer 1935, he openly advocated an Italian mandate for Ethiopia. Rather than upholding the Covenant, he sought to (a) leave open the possibility of Japan and Italy (and Germany) returning to the League, avoiding anything which might offend them, and (b) avoid crossing France and Britain, then in appeasement mode. This resulted in a ‘neutrality’ policy in which he avoided any mention of aggression and cut League programmes with potential political influence.

The British cartoonist David Low's famous take on the weakness of the League in the face of Japan.

The underlying politics became explicit over the 1939 Soviet invasion of Finland. Avenol was determined to have the USSR expelled, even though “[t]he Finns themselves had no particular wish to see Russia expelled” [16] (they wanted to stop the war and obtain assistance). A fervent anti-communist, Avenol believed that “so long as the Soviet Union is a member of the League it would be impossible for the League to function”.[17] He now worked the League machinery masterfully to enforce the Covenant: immediately seizing on a breach, trying unorthodox routes to bring it to the League’s attention, and lobbying extensively to secure the vote. Unfortunately, he did all this when the League could no longer play a decisive role, and the entire affair confirmed the impression of bias.[18]

From this Avenol may seem merely like a conservative French nationalist pursuing appeasement, like so many others did – shameful in retrospect, but not exceptional. This is the traditional view in the literature, that he “wished to represent what he viewed as correct French foreign policy”.[19] However, if we also analyse Avenol’s internal administrative measures, his behaviour in the crucial months of early 1940, and his own views of international organisation, we obtain a more nuanced view of his ‘internationalism’.

Administratively, Avenol changed the Secretariat’s management from a British civil service style of decentralised, bottom-up dynamics to a French cabinet style – a more hierarchical and highly centralised structure that “discourage[d] the spirit of initiative so important for any administrative body as the most vital check against bureaucratization”.[20] The change also gave Avenol direct control of all League matters, making him “virtually immune, at least within the Secretariat, to any questioning of his actions”.[21] A centralised system can have advantages, but it requires dedicated leadership from a hands-on secretary-general, and frequent boosts to staff morale. Neither were present.[22] Thus “[p]oorly led, many Secretariat sections lost their capacity for independent behind-the-scenes activism”.[23] Avenol’s reform aimed at de-emphasising political initiative by Secretariat officials. Additionally, he began in the late 1930s to drastically cut staff – partly as a necessary cost-cutting measure, partly as a way of purging anti-appeasers, such as France’s Marcel Hoden, Poland’s Ludwik Rajchman, and Britain’s Koni Zilliacus.[24]

Australian politician, diplomat and former Prime Minister Stanley Bruce spoke against the League sanctioning Japan and Italy in the crisis-ridden 1930s (picture from 1934).

This complemented his move away from political-diplomatic action (conflict-resolution) toward ‘technical’ work (socio-economic, scientific, and humanitarian). As the League’s political influence decreased, this proposal’s appeal increased. It peaked with the Bruce Report[25] of August 1939, which recommended creating a Central Committee for Economic and Social Questions, steered by member-states’ ministers of finance, health, transport etc., which would oversee technical bodies researching and proposing solutions to common problems.[26] The proposal “closely followed the views and opinions of the Secretary-General […marking] the high point of Avenol’s endeavour to turn the League into an organisation for economic and social cooperation in which political activities would be either eliminated entirely or reduced drastically”.[27] Avenol’s goal was to preserve what he saw as the League’s business, which did not include its legal principles. In January 1939, he commented that “practically the entire world was engaged in […] a demi-guerre in which the ordinary principles of order and international law were suspended”, so that the political side of the League should “remain dormant”.[28]

Apolitical technocracy or fascist internationalism?

Examining how Avenol’s policies fitted with alternative internationalist movements of the time, recent literature on fascist internationalism proves particularly helpful.

From Madeleine Herren to Mark Mazower, historians have recently explored the wide variety of Nazi and fascist plans for (and actual) international institutions, from the International Chamber of Law to the Deutsche Kongress Zentrale (“DKZ”), showing that, far from antagonistic to international organisation, fascist regimes actually had rather developed plans for international order – only with very different ‘internationalist’ principles and concepts to the League and the other post-1919 organisations.[29]

Particularly relevant are studies of fascist plans for corporatist international organisation, like Jens Steffeck’s[30] recent study of Giuseppe de Michelis’s 1934 World Reorganisation on Corporative Lines[31], one of the earliest and more influential works promoting such ideas. This was a branch of fascism bent on organising the world along rationalist lines, “exporting Italy’s socio-economic model of ‘corporativism’ to the rest of the world”.[32] The starting point was that “[t]he interdependencies in the global market required international cooperation to address the uneven distribution of labour, natural resources and capital across the globe. Only sustained international efforts at triangulation could bring these three resources fruitfully together”.[33] This ‘triangulation’ would occur between European powers and colonial territories under the auspices of a technocratic, economics-minded international organisation not unlike a League of Nations stripped of its legalistic (or, in the fascist view, hypocritically moralistic) dimension.

As Steffek notes, the parallels between this corporatist view and David Mitrany’s functionalist model of international organisation are striking: the belief in modern technocracy and systematic rationalisation, the primary focus on functionalism rather than legalism, the scientificism of a supposedly ‘apolitical’ bureaucracy. Avenol’s project came quite close to this, especially towards the late 1930s, when his conservativism and appeasement coalesced into a systemic view of international order. The Bruce Report, Avenol’s brainchild, was a model blueprint for corporatist international organisation. It was not necessarily a fascist plan (although Bruce was a notable appeaser, even during the ‘phoney war’ of 1940): it was a perfectly functionalist plan prioritising ‘technical’ socio-economic cooperation over legal or political structures. It was, in fact, realised after 1945 with ECOSOC – the crucial difference, however, is that ECOSOC was born alongside the very legalist (and political) structure of the UN, whereas Avenol’s conception involved substituting the League altogether for this kind of technical organisation.

Here Avenol’s behaviour in 1940, after the outbreak of war, becomes clearer. He planned to remake the League into a pan-European technocratic organisation serving the Axis[34], hoping that “[t]he increasing tension between England and its former ally France, and the tightening Nazi grip on Europe would assist in its execution”.[35] He grew convinced that the Axis would win the war, telling colleagues that the League “should work together with the Germans to expel the English from Europe” [36], and that “except for the Germans and Italians who have a program, a doctrine, and a method, no one seems to me to have one. [Their programmes] must not be rejected wholesale; they contain things which one can no longer reject […and that] 1941 will remain the starting point of a historic era; it is the end of the world of the 19thcentury. We are at the beginning of a great revolution”.[37] In July 1940 Avenol tried to approach the German Consul in Geneva to discuss these plans.[38] He enthused to one colleague that there would soon be “a new France, which was to be given a new soul to work in collaboration with Germany and Italy and keep the British out of Europe”.[39] To another he said that “Germany would military dominate Europe; he was not sure if Hitler wanted a League but fairly sure that Mussolini would, to form a certain balance”[40] – the idea seemed to be that a (fascistic) League with France and Italy could provide a measure of equilibrium with Germany.

James Barros' account of Joseph Avenol's Secretary-Generalship does not pick up on the nuances of his 'internationalism'.

In mid-July 1940 Avenol wrote to the new Vichy regime pledging his support: the administration replied telling him to resign (Pétain was wary of appearing close to the League).[41] After several convoluted attempts to prevent his deputy Sean Lester (who he considered disloyal due to his anti-appeasement stance) from succeeding him, Avenol tried to shut down the League by refusing to renew its budget. When that failed, in August 1940, he gave effect to his resignation and left for a weeklong trip to Vichy (unsuccessfully seeking a job in the new regime), leaving Lester to head the organisation. Lester would be the League’s final Secretary-General, seeing it through the war and transferring its work to the UN.

Towards the end of the war, Avenol published a book, L’Europe Silencieuse (‘Silent Europe’)[42], in which he outlines his views on postwar international organisation - a fascinating document, as much for what it does not say as for what it does. He goes on at length on the need for economic cooperation, rational management structures and the ‘élan vital’ of Europe. He obsessively categorises states by their economic power and demographic ‘energy’. Absent are discussions of international law, rights, and – not least – international service.

Conclusion

Considering the multiplicity of internationalisms, the similarities between fascist internationalism and liberal functionalism, and the fate of other institutions at the time, we can see that Avenol’s plans were not as far-fetched as often thought. Many other international organisations, voluntarily or not, did go fascist before or during the war. As Sandrine Kott observed, once the war started several “technical bodies like the International Bureau of Education or the Bank for International Settlements were collaborating with the Nazis”.[43] The International Criminal Police Commission (later Interpol) effectively became a Nazi organisation during the war, moving its headquarters to Berlin and having as its presidents SS generals, including Reinhard Heydrich and Ernst Kaltenbrunner.

The question then becomes not ‘how could Avenol behave thus?’, which is what is usually asked, but rather ‘why did the League not suffer the same fate as those other institutions?’. Mazower suggests that the League “was altogether a bigger and ideologically vastly more loaded proposition, and Avenol, who did put out feelers to Pétain, completely misjudged the situation”.[44] The key is what constituted that ‘loaded’ proposition. Part of it was the inherent legalism of the League’s brand of internationalism, the source of such hatred from fascists and Nazis, from Carl Schmitt onwards, who wanted to “expose the League’s internationalism for the sham it really was”.[45] Thus, my initial argument that studying Avenol’s tenure, by showing alternative ways that League official could act internationally, reinforces Karen Gram-Skjoldager point that the Secretariat “serves as a prism through which we can grasp the broader ecosystem of social and political systems of the time”.[46]

Studying the Avenol years helps us reassess the typical dichotomies we use for the study of international organisations and the interwar period – political/technical, internationalist/nationalist – forcing us to refine our theoretical and methodological lenses. Many of the answers are difficult to find – as they were then – but it is rather important that we get at least the questions right.

References

[1] E.g. Rovine, A., The First 50 Years: the Secretary-General in World Politics (Leiden: A.W. Sijthoff, 1970); Barros, J., Betrayal from Within – Joseph Avenol, Secretary-General of the League of Nations, 1933-1940 (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1969).

[2] ‘Organisation of the League of Nations’ (31/5/1919), TNA FO 608/242.

[3] ‘Organisation of the League of Nations’, LNA 29/749/38.

[4] ‘Staff and Organisation of the Secretariat’ (5/1920), LNA 29/6890/1083, 4.

[5] ‘Balfour Report’ (19/5/1920), LNA 29/4434/1083, 3.

[6] ‘Report of the Committee of Experts (Noblemaire Report)’ (7/5/1921), LNOJ– Records of the Second Assembly, Fourth Committee Minutes.

[7] ‘Statutes for the Personnel of the Secretariat’ (1922), LNA 30/11713, 4.

[8] ‘Staff Regulations – 1945’, LNA 18A/2892/563, 4. For a study of the establishment of the staff regulations and early recruitment patterns as a way of balancing legitimacy and autonomy, see: Gram-Skjoldager, K. and Ikonomou, H. A., ‘The Construction of the League of Nations Secretariat. Formative Practices of Autonomy and Legitimacy in International Organizations’, International History Review 2017 (e-publication available here: http://www.tandfonline.com/eprint/sB5YCEjYYjpwfUT9Wdaz/full).

[9] Sending, O. J., ‘The International Civil Servant’, International Political Sociology 8:3 (2014), 338-339.

[10] ‘Report of the Committee of Enquiry on the Organisation of the Secretariat,the International Labour Office, and the Registry of the Permanent Court of International Justice (The Committee of Thirteen)’, Records of the Eleventh Assembly, Fourth Committee Minutes, LNA S.929, 8.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Pedersen, S., ‘The League of Nations Secretariat as a Site of Political Imagination’, Annual Nicolai Rubinstein Lecture in Intellectual History and the History of Political Thought, Queen Mary University of London (lecture delivered on 15 March 2017).

[13] Pedersen, S., The Guardians – The League of Nations and the crisis of empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 54-59.

[14] League of Nations Directors’ Meeting Minutes no.74 (28/2/1923), quoted in Pedersen: 2015, 45.

[15] Barros, J., Betrayal from Within – Joseph Avenol, Secretary-General of the League of Nations, 1933-1940 (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1969), 57, 77.

[16] Walters, F.P., A History of the League of Nations(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1960), 807.

[17] Quoted in Barros: 1969, 198.

[18] Bendiner, E., A Time of Angels – The Tragicomic History of the League of Nations (New York: Knopf, 1975), 397.

[19] Rovine: 1970, 137.

[20] Ibid., 155.

[21] Barros: 1969, 23.

[22] Pedersen: 2017.

[23] Pedersen: 2015, 294.

[24] Barros: 1969, 173-175.

[25] ‘The Development of International Cooperation in Economic and Social Affairs’ (22/8/1939), LNA A.23.1939.

[26] Walters: 1960, 762.

[27] Barros: 1969, 195-196.

[28] Quoted in Barros: 1969, 189.

[29] See, e.g. Herren, M., ‘Fascist Internationalism’ in Sluga, G. and Clavin, P. (eds.), Internationalisms: A Twentieth-Century History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017); Martin, B., The Nazi-Fascist World Order for European Culture (London: Harvard University Press, 2016); Mazower, M., Governing the World – The History of an Idea (London, Allen Lane, 2012).

[30] Steffek, J., ‘Fascist Internationalism’, Millennium 44:1 (2015).

[31] Michelis, G. de, World Reorganisation on Corporative Lines (London: G. Allen & Unwin, 1935).

[32] Steffek: 2015, 4.

[33] Ibid, 9.

[34] Gageby, D., The Last Secretary-General: Sean Lester and the League of Nations (London: Town House, 1999), 192.

[35] Barros: 1969, 233.

[36] Rovine: 1970, 160.

[37] Quoted in Rovine: 1970, 160.

[38] Gageby 1999, 190.

[39] Quoted in Barros: 1969, 233.

[40] Quoted in Gageby: 1999, 192.

[41] Rovine: 1970, 159.

[42] Avenol, J., L’Europe Silencieuse (Neuchatel: Editions de la Baconniere, 1944).

[43] Kott, S., ‘Fighting the War or Preparing for Peace? The ILO during the Second World War’, Journal of Modern European History 12:3 (2014), 366.

[44] Mazower: 2012, 192.

[45] Ibid, 181.

[46] Gram-Skjoldager, K., ‘Between Internationalism and National Socialism - Helmer Rosting in the League of Nations Secretariat’, entry in the blog The Invention of International Bureaucracy (11/3/2016).

Images

1) Berlinische Galerie: ''Joseph Avenol, Generalsekretar des Völkerbundes, in seinem Büro in Genf'' http://sammlung-online.berlinischegalerie.de/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=18473&viewType=detailView

2) David Low, 1932 (Associated Newspapers Ltd./Solo Syndication) https://www.emaze.com/@AWLFOQIR/THE-CARTOON

3) Stanley Bruce, 1934 (National Library of Australia) http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-157855246/view

4) James Barros Betrayal From Within: Joseph Avenol, Secretary of the League of Nations, 1933-1940 (Yale University Press, 1969). Book cover. https://www.abebooks.co.uk/book-search/title/betrayal-from-within/author/barros/