Israel Zangwill on Nationality and “The League of Damnations”

Laura Almagor (LSE Teaching Fellow - Department of International History)

Never in fact in human history has anything been so written about and so little thought out as the League of Nations.[1]

Harsh words, penned in 1920 by the Anglo-Jewish fiction writer, political actor and commentator Israel Zangwill (1864-1926). The literary gentleman had much more to say, and often in even more damning terms, about the Versailles Peace Treaty, president Woodrow Wilson, and what he termed the “League of Damnations”. But a critic may very well also be an idealist and there was a lot in the underlying ideals of the League that appealed to Zangwill. However, rapidly unfulfilled hopes in connection to the new organization made him lament the disappointing realities of world politics at war’s end.

Israel Zangwill, circa 1905.

The publications most extensively portraying Zangwill’s opinions on the League are The Principle of Nationalities, which served as the 1917 Conway Memorial Lecture, and The Voice of Jerusalem (1920), a critical reflection on universalist Jewish values, the post-war world order, as well as on Zangwill’s own publication record on these topics. In the following, an in-depth analysis of these texts will take center stage. Thus far, the Anglo-Jewish author’s biographers and other scholars interested in “Zangwilliana” have not exactly ignored these seminal publications, but an exploration of the political significance of the rapid change in outlook that these texts display, especially vis-à-vis the League of Nations, has yet to be performed. It is in this realm that the current contribution breaks new ground.[2]

But what do we gain from zooming in on the opinions of this remarkable, albeit nowadays largely forgotten figure? First of all, Zangwill’s views render him an intellectual “connector” between the history of the League of Nations’ and Jewish history and politico-religious thought. The historical pivotal points in this story are the British issuing of the Balfour Declaration in 1917 — promising a Jewish National Home to the Zionist Movement in soon-to-be British Mandate Palestine, and the subsequent reneging on this promise culminating in the 1922 Churchill White Paper. Secondly, the Anglo-Jewish writer demonstrated a sharp eye for the cynical realities behind the seemingly universalistic ideals undergirding the League’s inception, and his publications on the topic reveal Zangwill as a foresighted and exceptionally eloquent realist. Often straying from the mainstream political path, he was nevertheless a representative of the generally pro-British Anglo-Jewish elite, and an important opinionmaker in both the Jewish and non-Jewish, as well as the British and American public sphere.

Israel Zangwill

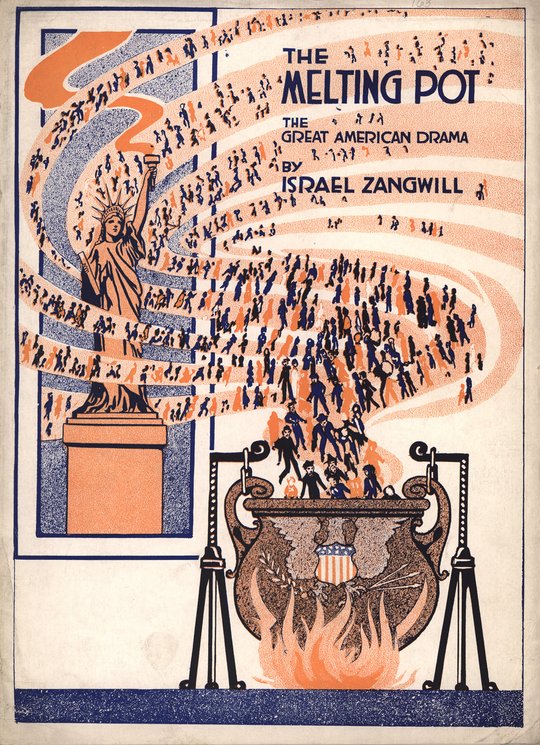

For those not well-versed in either Zionist history or Victorian-era literature, the name Israel Zangwill may not ring all that familiar. However, the erstwhile literary giant’s eventual obscurity would have been surprising to his educated contemporaries. Once termed the “Dickens of the Ghetto” and compared to Leo Tolstoy, Heinrich Heine, Thomas Hardy, Henry James, George Bernard Shaw and Rudyard Kipling, Zangwill was a household name in both Anglo-Jewish and gentile circles and a much-respected political activist and commentator. Besides authoring literary classics such as Children of the Ghetto (1892) and the play The Melting Pot (1908)— popularizing that term to refer to American multiculturalism — the London-born Zangwill was an avid agitator on behalf of suffragism. He was also a highly sought-after publicist and public speaker on a wide variety of other issues, ranging from minority rights — first and foremost, but certainly not exclusively, for the Jews — to biting commentaries-turned-polemics with famous anti-Semites and even with the Ku Klux Klan. In addition to his written works, Zangwill was one of the most important early Zionists. In 1905, Zangwill seceded from the Zionist movement to head the so-called Jewish Territorialist Organisation (ITO) until its dissolution in 1925. In that capacity, Zangwill negotiated with numerous international government representatives in his attempt to find territories for Jewish settlement.[3]

Cover of Theater Programme for Israel Zangwill's play "The Melting Pot" (1908), 1916.

For several decades Zangwill was thus an international celebrity. Despite the occasional rediscovery of his literary writings, as well as the recent resurfacing of his name in several studies trying to recover the “Lost Atlantis” of non-Zionist Jewish politics,[4] Zangwill is now a largely forgotten figure. The reasons for this departure into oblivion could be summarized by the inscription on Zangwill’s columbarium in London’s Liberal Jewish cemetery, undoubtedly penned by the writer himself before his death: “A Man of Letters and a Fighter of Unpopular Causes.”[5]

London County Council Blue Plaque.

Several of Zangwill’s “unpopular causes”, however, have gained in topicality during the more than 90 years that have passed since his death. Lingering gender inequality suggests that the accomplishments of the suffragist movement have not consolidated what its proponents set out to achieve. Moreover, disgruntled leftist Israeli youth asked some years ago: “Lama lo Uganda?” (“Why not Uganda?”),[6] referring to the 1903 British offer to the Zionists of a part of the British African possessions. The rejection of this proposal spurred Zangwill to establish the ITO in 1905. When one dives into Zangwill’s extensive political writings, one finds that he demonstrated deep insights into a wide range of political developments. For instance, he heavily criticized the British and Zionist activities in the Middle East in the face of the opposition posed by the existing Arab population of Palestine. Particularly insightful are Zangwill’s reflections on the League of Nations during its early years. A committed pacifist, the notion of a supranational body governing world peace surely spoke to Zangwill, but as a cynical realist he also scrutinized the League, which he rapidly deemed a failure.

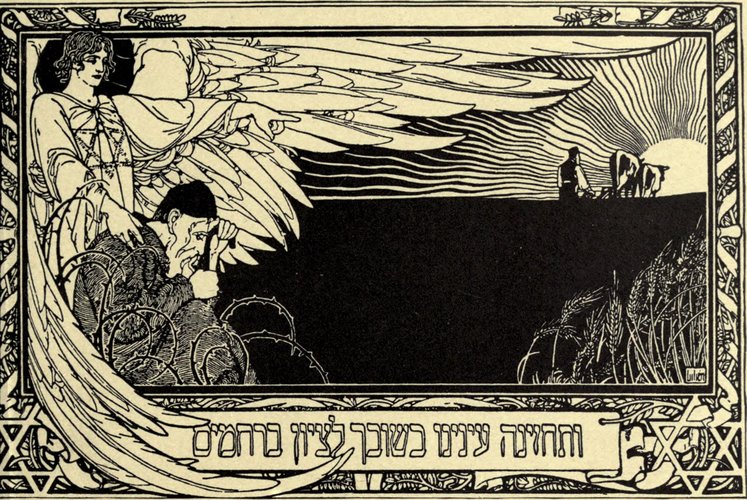

Engraving by Ephraim Moshe Lilien, produced for the 5th Zionist Congress, which took place in Basel in 1901. The Hebrew inscription at the bottom is the prayer “May our eyes behold your return in mercy to Zion.”

“Nationality”

As the First World War was approaching its end, the concept of the “nation” came to stand at the center of the discussions as to the exact makeup of the postwar world. Not coincidentally, it was exactly the word “nation” that was to become one of the constitutive elements of a “League of Nations.” What was this “principle of nationalities,” Zangwill asked, for which so many men had lost their lives and were likely to die in the future? The writer considered this “master-principle” in ominous terms: “When States and Kingdoms talk of truth and justice, ‘Earth,’ said Wordsworth, ‘is sick and Heaven is weary’.”[7] Also in the light of the recent atrocities, Zangwill did not harbor much faith in the moral abilities of mankind.[8]

Whatever the future would hold, the term “nationality” was not going to be of much practical value. After all, neither wolves nor oxen were self-conscious about their belonging to a pack or a herd; “is it necessary for some gifted ox-tongue to proclaim their bovi-nationality?”[9] Useful or not, the concept did need to be defined once and for all. Formulating such a definition was not a simple task. Fixing “nationality” based on geographical realities made no sense. “Indeed, if the early races [sic.] had been scattered by Miltonic or Teutonic archangels, with or without Zeppelins, they could scarcely have been more mixed today.” Nationality, Zangwill concluded, was therefore nothing else than “a state of mind corresponding to a political fact.”[10]

Two men, one brother

This constructivist (in contrast to primordial) understanding of nationality meant that as political facts changed nationalities were also not fixed: “[t]he notion that Nationalities are immortal is obscurantist.”[11] The changeability of the concept made it a dangerous thing: “Nationality, deep as life, but narrow as the grave, is closing in on us.” What made this situation even more perilous was the fact that religion was giving way to “nationality” (by which Zangwill here in fact meant “nationalism”) as a permanent placeholder for cohesive shared experiences, especially in times of violent crisis. “[T]he Lord God Patrie was a jealous god,” leaving no space for other, more benign forms of group identity.[12]

Despite its demise, Zangwill did nonetheless distinguish a continued role for religion in the universalistic ambitions connected to the League of Nations. He cherished a lifelong interest in the Jewish roots of Christianity and was well-versed in Jewish tradition. The famed author made it a point to show the Jewish underpinnings of the spirit guiding the Wilsonian project. Judaism’s messianic streaks had always been based on the notion of a Jewish mission for the betterment of mankind. In that vein, Zangwill urged for an investment in the universalization of Jewish-inspired tribalism. In effect, “the brotherhood of peoples” would be strengthened: “It takes two men to make one brother.”[13]

The price for such an unavoidable investment in the strengthening of smaller national units would be to relinquish the notion of a powerful “World-League”. Unity only arises in opposition to an external adversary, or so Zangwill claimed: “World-Nationality would arrive tomorrow if only the Martians would invade us.” He did offer a solution to this conundrum for the future League of Nations: the supranational body should do away with “nationality” and sovereign states, and invest in different kinds of class-based, religious, artistic or scientific “brotherhoods”. Zangwill conceded the unlikeliness of this scenario, and therefore he proposed a true investment in a moral system of nationalities, based on “Reason and Love”, aimed at freedom from oppression.[14]

The League of Damnations

Three years after this in-depth exploration of nations and nationalities (despite his call not to conflate them even Zangwill himself used the terms interchangeably), The Voice of Jerusalem was able to reflect on the now existing League of Nations. In a 1917 speech given on the occasion of the issuing of the Balfour Declaration, Zangwill had still praised the developing League, without which “the whole world will perish.” By 1920, the overall verdict had become damning: the endeavor had turned out a “fiasco”.[15]

Zangwill solemnly concluded that the fact that “humanity standing at the cross-roads of history should have failed to take the turning to the right, is the saddest episode in all man’s long tragic adventure.” It was not, he lamented, “a League of Nations that has been brought forth, but a League of Damnations.” Instead of a “League of Love”, the organization had in fact become a perpetuation of the bad old world order, an attempt to end “‘the war against war’ by a Peace against Peace” that would never allow true peace.[16]

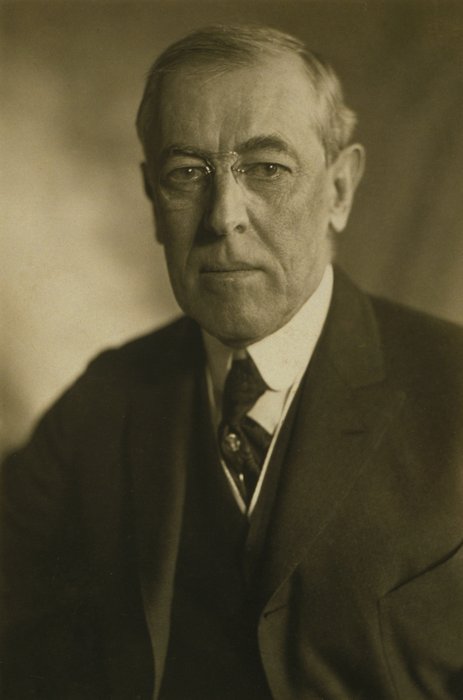

President Woodrow Wilson.

The main culprit of this epic failure was president Woodrow Wilson, who had so disastrously architected the League. Interestingly, Wilson largely shared Zangwill’s liberal values, which in fact undergirded the American president’s desire to present the Treaty of Versailles and the League as a “readjustment of those great injustices which underlie the whole structure of European and Asiatic society.” The system of bilateral agreements between individual (European) states had failed, but now, under the League’s guidance, states and sovereigns with their imperialistic ambitions were no longer to rule the world, but instead the new ruler was “the power of the united moral forces of the world, and in the Covenant of the League of Nations the moral forces of the world are mobilized.”[17] Even if such universalistic language would have certainly appealed to Zangwill, he shared with several other commentators the opinion that Wilson had nonetheless shown himself not just incompetent, but also arrogant, sporting a sense of “papal infallibility”. Instead of acknowledging his own defeat in the negotiation process, Wilson had “triumphantly waved scraps of paper from which the Fourteen Points have been practically erased.”[18]

A Jewish Moral Vanguard

Much of Zangwill’s discontent with the League had to do with his own long-standing (albeit problematic) engagement with the Zionist project in Palestine. The 1917 Balfour Declaration had quickly revealed itself as a pipe dream, and the subsequent mandate system, in which several areas, including Palestine, Syria and Iraq, were placed under Great Power tutelage until they “matured” enough to gain independence, turned out to be an obscured system of dividing the spoils of war between the victorious powers. Zangwill criticized the Zionists for having failed to grasp that they had been used as a pawn, and for not having acted upon opportunities when these had presented themselves. The most striking missed opportunity of both the Zionists and the international community, Zangwill argued, was the failure to stimulate the Palestinian Arabs to migrate to the newly established Arab states in the region to make place for Jewish settlers from Europe. “Race redistribution in the interests of the general world-happiness is, I take it, one of the functions of the League of Nations[.]”[19]

Franz Krauss, 1936, ‘Visit Palestine’ tourism poster.

The mandates were thus a scam, a “new-fangled hypocrisy,” meant to cover up the lust for new colonies on the part of the Great Powers. “How European statesmen are able to […] keep from winking when talking to us of these moral ‘Mandates,’ which so mysteriously correspond with their secret treaties and ambitions, is a standing marvel. They must assuredly assume in us a sancta simplicitas beyond the sucking babe’s.” Whereas officially the mandate system was supposed to safeguard some form of justice in the governed areas, in Africa, most of which was nominally outside of the system, “the white man is allowed to batten upon the negro […] unrestrained by international control.”[20]

Surprisingly, most of this rant against the League served to support the mildly hopeful message that Zangwill had already set out to convey in The Principle of Nationalities: true universalistic morality did exist in the millennia-old Jewish messianic tradition. After all, it was the “vision of our [the Jews’] own Isaiah: ‘They shall beat their swords into plough-shares and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift sword against nation, neither shall there be war anymore’.” This moral imperative constituted the “Voice of Jerusalem” and could be extrapolated to guide a real and sound League of Nations project. If different peoples and creeds would invest in their own betterment with this “Voice” in mind, without “that crude and cynical view of nationality which regards every nation as necessarily the enemy of every other,” the “brotherhood of man” would be achieved.[21]

In practical terms, and anticipating the era of decolonization, Zangwill therefore suggested to replace the “discredited” The Hague Peace Palace with a Temple of Peace in Jerusalem. With large parts of Asia and Africa still practically undeveloped and with a growing westward gaze on the part of the biggest non-western players India and Japan, Jerusalem could have an important role to play. “In the Holy City of three great religions even diplomatists might find cynicism difficult, and our poor battered humanity might take a fresh upward impulse of faith and hope.” Such a Jerusalem-based institution might counteract the evils of nations. Individuals may have good intentions, but “in our corporate capacity we are demoniac.”[22]

Conclusion: Against the Grain

Zangwill’s writings on nationality and the League of Nations provide insights into the overall dark perspective of a well-known Jewish political and cultural figure at the time of the birth of the world organization. Even before most other liberal intellectuals abandoned their “near-millennial expectations” of world peace that Wilson had inspired, Zangwill’s reflections anticipated later criticism of the overall project. The Englishman’s publications also bring together the respective histories of the League and of one of the most visible minorities in twentieth century political history. It may have been his membership in this Jewish minority group that led Zangwill to profess a disillusionment in the League’s capacities that resembled the growing disappointment experienced by the colonized nations throughout 1919. For a brief period, these dependent peoples had hoped the “Wilsonian Moment” would enable them to obtain some form of self-determination through a transformation of the world order. That hope now proven idle—even Wilson himself had never been interested in breaking up the western colonial empires—colonial leaders started faring a generally less peaceful course towards independence in the ostensibly only workable shape of the nation-state.[23]

In an era when such statehood was becoming ever more the accepted norm, despite the lofty universalistic ideals that seemed to constitute the League’s official rationale, Zangwill went against the grain by arguing against the merits of the nation-state. At the same time, he never fully gave up on the League’s future.On the contrary, he was convinced that if state and bureaucratic borders between peoples would finally be overcome, if the “mania for ‘sovereign rights’” of both western and non-western peoples could be brought to an end, then the ideals of a world community could also be met.[24]

References

[1] Israel Zangwill, The Voice of Jerusalem (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1921), 120-1.

[2] This article therefore focuses on a small selection of published sources. For the most extensive collection of primary sources related to Israel Zangwill, I refer the reader to the writer’s personal archives (collection number A120), as well as the archives of the ITO (collection number A36), both held at the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem.

[3] For the best recent biography on Zangwill, see Meri-Jane Rochelson, A Jew in the Public Arena:The Career of Israel Zangwill (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2008). For more on Zangwill’s activities as a Territorialist, see Gur Alroey, Zionism without Zion. The Jewish Territorial Organization and its Conflict with the Zionist Organization (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2016), Adam Rovner, In the Shadow of Zion: Promised Lands before Israel (New York: NYU Press, 2014), as well as my doctoral dissertation: Laura Almagor, Forgotten Alternatives. Jewish Territorialism as a Movement of Political Action and Ideology, 1905–1965 (Florence: European University Institute, 2015).

[4] David Myers,“Rethinking Sovereignty and Autonomy: New Currents in the History of Jewish Nationalism”, Transversal 13, 1 (2015), 44-51:48, 50. Scholars who in recent years have contributed to this broader Jewish political narrative are, amongst others, Noam Pianko, Joshua Karlip, Kenneth B. Moss, Kalman Weiser, James Loeffler, Dmitry Shumsky, Adam Rovner, David E. Fishman, Jeffrey Shandler, Stefan Vogt, Joshua Shanes, and Simon Rabinovitch.

[5] Rovner, In the Shadow of Zion, 114.

[6] See, for instance a somewhat ludicrous videoclip, in which three Israeli comedians pose this same question: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sgcdo2Ovj0k (9.1.2019).

[7] Israel Zangwill, The Principle of Nationalities, (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1921), 14-5, 13.

[8] Ibid., 26.

[9] Ibid., 33, 29-10.

[10] Ibid., 37, 46.

[11] Ibid., 67. See also Zangwill, The Voice of Jerusalem, 12.

[12] Zangwill, The Principle of Nationalities, 79, 84-5.

[13] Ibid., 96, 91-2, 98-9.

[14] Ibid., 96, 99-100, 107.

[15] Zangwill, The Voice of Jerusalem: 85, 115, 120.

[16] Ibid., 120, 123, 122, 127-8.

[17] Woodrow Wilson, “League of Nations” [also known as the “Pueblo Speech”], 25 September 1919. Full text at: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=117400 (9.01.2019).

[18] Zangwill, The Voice of Jerusalem, 120-1. French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau famously complained about Wilson’s supposed over-zealous arrogance when he exclaimed: “Mr. Wilson bores me with his Fourteen Points; why, God Almighty has only Ten!”, quoted in Dixon Wecter, The Hero in America: A Chronicle of Hero-worship (New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1941), 402.

[19] Zangwill, The Voice of Jerusalem, 105. The Englishman’s short-lived promotion of such a population exchange scheme, however much in line with dominant geopolitical convictions that lasted well into the post-1945 period — as also Mads Drange’s contribution to this blog shows — was to gain him the not entirely deserved reputation of a hardliner regarding the Arab Question in Palestine. See, a.o., Rochelson, A Jew in the Public Arena, 166, and Almagor, “Forgotten Alternatives,” 113-5.

[20] Zangwill, The Voice of Jerusalem, 101, 115, 125. Erez Manela also extensively argues that the “Wilsonian moment” in fact served to help perpetuate the existing imperial system: Erez Manela, The Wilsonian Moment. Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

[21] Zangwill, The Voice of Jerusalem, 85.

[22] Ibid., 100, 125.

[23] Manela, The Wilsonian Moment, 13, 5, 9.

[24] Zangwill, The Voice of Jerusalem, 130, 132.

Images

1) Israel Zangwill, circa 1905. Source: Library of Congress.

2) Cover of Theater Programme for Israel Zangwill's play "The Melting Pot" (1908), 1916. Source: University of Iowa Libraries Special Collections Department.

3) London County Council Blue Plaque. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

4) Engraving by Ephraim Moshe Lilien, produced for the 5th Zionist Congress, which took place in Basel in 1901. The Hebrew inscription at the bottom is the prayer “May our eyes behold your return in mercy to Zion.” Source: Milwaukee Jewish Artist’s Laboratory.

5) President Woodrow Wilson. Source: Library of Congress.

6) Franz Krauss, 1936, ‘Visit Palestine’ tourism poster. Source: Palestine Poster Project.