‘He used to give me Turkish lessons in Constantinople’: How to get a job in the League Secretariat

Haakon A. Ikonomou (postdoc - Aarhus University)

Strangely, the early staffing of the very first international bureaucracy of a world organisation was conducted in a distinctly un-bureaucratic manner.

A substantial part of the Invention of International Bureaucracy project concerns the recruitment practices of the League of Nations Secretariat. This was, after all, how the Secretariat was filled with people and personalities that came to shape the institution, and international politics more broadly, throughout its existence. Retaining the right to hire, fire and promote people as they saw fit was, moreover, among the most important sources of autonomy for the League Secretariat. If it could not choose its own human composition, how could it act independently of, or rather manoeuvre relatively unconstrained between, narrow state interests?

But how did people get into the League Secretariat? This blog will look at one specific road into international bureaucracy, to draw up some more general insights about the recruitment practices of the League: The overall argument being that while the recruitment practices of the Secretariat became increasingly institutionalized, professionalized and routinized – setting the standard for following generations of International Organizations – the early recruitments were often the product of haphazard encounters and nebulous networks. As this first generation of League officials arguably had a disproportionately large impact on the organization, this seems a relevant point to explore.

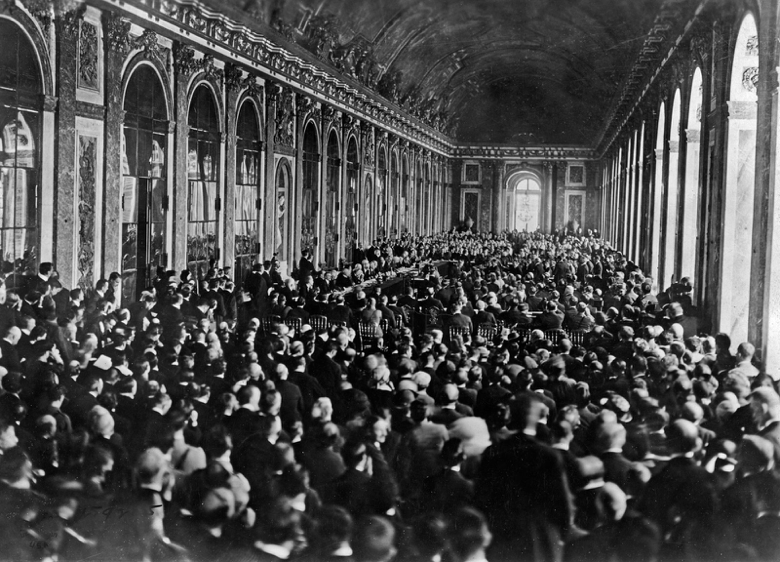

Dignitaries gathering in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles, France, to sign the Treaty of Versailles

Moment of Flux

From the looks of the early existence of the League Secretariat, setting up an international secretariat is a bit like putting on clothes while running a race – you don’t want to be left behind from the start of the race and you most definitely don’t want to cross the finish line a half-dressed buffoon.

In other words, the first Secretary-General Sir Eric Drummond – himself not the first-choice candidate for the job – had to make the Secretariat functional and operational from the very beginning, to handle all kinds of political, social and economic matters following the Great War. Matters, that would not wait politely for the organisation to find its shape. On the other hand, Drummond also had to make strategic choices both in terms of personnel and with regard to the structure of the Secretariat, that would have long-term impact on its workings, and determine whether it could ‘go the distance’.

In the beginning, Drummond, therefore, balanced between pragmatic ad hoc solutions and principled decisions, developing what his right-hand and confidant Frank P. Walters called “a small but elastic organism”.[1] His more principled decisions concerned particularly two things: that the Secretariat should be composed of a truly international staff, organised along functional, rather than national, lines. Thus, there would be no ‘French Section’, composed of French experts, bureaucrats and diplomats representing French interests, but rather a ‘Health Section’ and an ‘Information Section’, composed of people from different nationalities working together on a specific functionally limited subject.

The other major principled decision was to retain absolute autonomy in terms of staffing. This did not mean that the Secretariat was beyond pressure from Member States to take on certain candidates for specific posts – far from it. But it meant that the final decision in terms of staffing ultimately lay with Drummond himself, and that this principle, whether real or cosmetic in practice, had to be upheld for the Secretariat to survive as a distinct ‘organism’.[2]

With time, the Secretariat’s staffing practices settled in bureaucratic procedures and formal institutions, but what about in the very beginning?

Many of these people found their way into the Secretariat via the Paris Peace Conference. Thinking that Paris in the late spring and summer of 1919 held an unprecedented pool of talented men and women, Drummond strategically waited until the Peace Conference drew to a close, and seized upon this great moment of flux to recruit a small team of employees that would shape the institution profoundly.[3] One of the employees, Drummond hired was a young Greek diplomat.

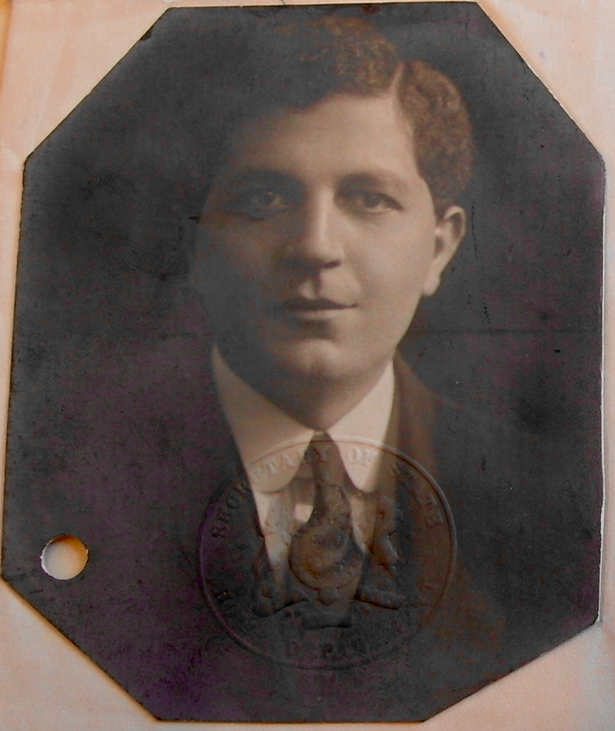

A young Thanassis Aghnides, from his Personnel File at the League of Nations

Thanassis Aghnides gets a job

Now, several of the men and women that landed jobs within the Secretariat in the spring and summer months of 1919 were either people Drummond knew and trusted, or came recommended by people he knew and trusted. Furthermore, Drummond had to consider the national composition of the early team: top positions were reserved for Britain, France, Italy and the United States (before withdrawal), without whose support and involvement the League would lose legitimacy and force. Still, these early recruitments followed no structured pattern, no formalised rules, and was not assessed by any permanent competent body.

It was this situation that gave the young Ottoman Greek, Thanassis Aghnides, an opportunity that would change the course of his life.

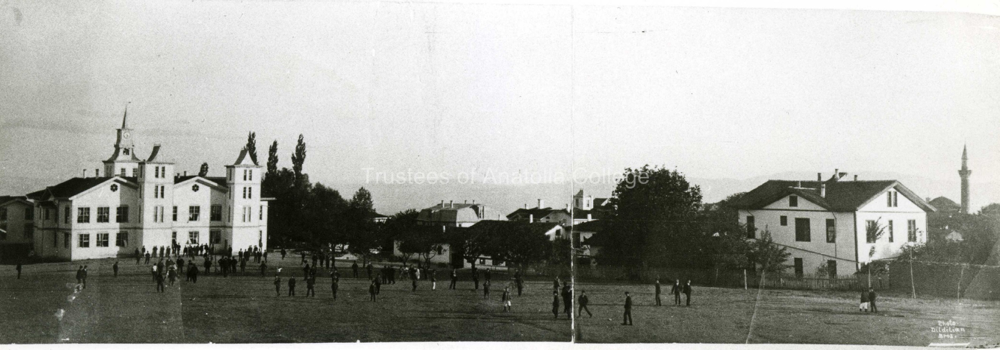

Born and raised in the Anatolian heartland and Constantinople, Aghnides attended two different missionary schools during the course of his education. After graduating from the Grand Patriarchal School in Phanar, a Greek Orthodox School, he received his baccalaurat from the French Catholic College of St. Joseph before taking a further degree at the American Protestant Anatolian College.[4] This strange mixture of religious and linguistic experiences, and his excellent grades in calligraphy, arithmetic, geography and other disciplines, qualified him for legal studies in Constantinople.[5] Here, due to his proficiency in French, English, Turkish and Greek, Aghnides was pulled into the cosmopolite diplomatic scene of the old polyglot melting-pot, eventually landing the job as personal Turkish teacher for the ascending British diplomatic star Harold Nicolson.

Campus of Anatolia College in Merzifon, early 1900s.

Campus of Anatolia College in Merzifon, early 1900s.

As Turkish nationalism grew more fervent, and Greek and Armenian minorities – themselves in the grasp of nationalist fever – faced an increasingly perilous existence in the crumbling Ottoman Empire, Aghnides moved to Paris, in 1911, to retake his law degree in French at the Sorbonne. When war came, Aghnides – possessing many of the skills needed for the diplomatic trade – was recruited by the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and soon appointed director of the Press Bureau at the Greek Embassy in London.[6] Though the circumstances are unclear, he did not get along with his superiors and quit the foreign service at the close of the war.[7]

At the close of the First World War, Aghnides found himself unemployed, torn between a modestly successful career in music; pursuing his legal studies; and continuing within the diplomatic profession. A strange encounter would decide his path: His former Turkish pupil from Constantinople, and acquaintance from the London-days, Harold Nicolson, now a part of the British Delegation at the Peace Conference.

After Aghnides had confided to Nicolson that he was very much looking for some kind of professional direction, Nicolson wrote to Drummond:

“I wish to recommend to you a young Greek who would, I think, be extremely valuable on the International Secretariat (…) I have known him for the last six years as he used to give me Turkish lessons in Constantinople. (…) I can guarantee that he is exactly the sort of person you would want, and I think it would be a great pity if we failed to secure his services.”[8]

So keen to convey the virtues of this young Greek was Nicolson, it seems, that he forgot to mention his name. “You do not mention his name: could you kindly let me have it?”, Drummond wrote back.[9]

Thus, began Thanassis Aghnides’ remarkable career in the League Secretariat. Aghnides would, after spending most of his first years in the Political Section, rise to the post of Director of the Disarmament Section in 1930, heading it in the crucial years of the failed World Disarmament Conference (1932-34). From 1939 to 1942, he was Under Secretary-General of the League of Nations in charge of Department I of the Secretariat, playing an important role, together with Secretary-General Seán Lester, in keeping the machinery going and rendering the technical and humanitarian elements of the League operational. Aghnides would stay with the Secretariat for 23 years.

A visualization of how long staff, broken down by year of first employment, stayed on in the League Secretariat

The significance of the first employees

The circumstances of Aghnides’ recruitment to the League Secretariat are significant for several reasons. First, it shows very clearly the relative randomness of the early staffing of the Secretariat, which was the product of the Secretariat’s acute need for able men and women in order to become operational as soon as possible, Drummond’s remarkable autonomy in recruiting staff in the first months of the Secretariat’s existence, and the unprecedented pool of talent gathered in, or connected to, the Paris Peace Conference. People like Alexander Loveday, Jean Monnet and Pierre Comert, all joined the provisional Secretariat (located in London) in the ‘moment of flux’. Second, as is displayed in the graph above, those employed in 1919, and the subsequent three or four years, would stay significantly longer than the international bureaucrats recruited in the following years.

Third, the fact that they stayed on for a longer time, combined with the many early strategic and institutional decisions they had to make, which would shape the League of Nations’ organisational make-up for the remainder of its existence, meant that the first cohorts of international bureaucrats wielded a disproportionate amount of administrative power.[10] Some, like for example Erik Colban (Director of the Administrative and Minorities) or Alexander Loveday (Member, then Chief of the Economic and Financial Section, and Director of the Financial Section and Economic Intelligence Service), would develop entire sub-fields of international governance.[11]

This is, in itself, not so surprising, as theories and studies of ‘path-dependency’ and ‘the importance of early decisions’ are plenty, However, the career of Thanassis Aghnides shows, that when we study what international bureaucracies do and how they work, we need to consider historical contingencies and biographical trajectories just as carefully as we analyse institutional structures, political procedures and administrative norms.

References:

[1] LONA, R182 Walters to Secretary-General Drummond, 17 July 1919.

[2] Karen Gram-Skjoldager and Haakon A. Ikonomou “The Construction of the League of Nations Secretariat. Formative Practices of Autonomy and Legitimacy in International Organisations”, unpublished paper.

[3] LONA R1455 Response to Wiseman’s scheme, 30 April 1919, E. Drummond.

[4] Thanassis Aghnides “About the author” in Status of the Oecumenical Patriarchate based on the Provisions of the Treaty of Lausanne – International Standing of the Oecumenical Throne, New York, 1964.

[5] Institut des Frères des Écoles Chrétiennes. Collège Saint-Joseph A Kadi-Keuï. Distribution Solennelle des Prix présidée par Son Excellence Monsieur Constans, Ambassadeur de France, prés la sublime porte, Le 8 Juillet 1903, Contantinople; William McGrew Educating Across Cultures. Anatolia College in Turkey and Greece, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015, p. 126.

[6] Thanassis Aghnides “About the author” in Status of the Oecumenical Patriarchate based on the Provisions of the Treaty of Lausanne – International Standing of the Oecumenical Throne, New York, 1964.

[7] LONA P273 “Interview with Thanassis Aghnides”, Geneva: Centre de Reserches sur les institutions internationales, 1966, p. 3-4.

[8] LONA S699-700 My dear Drummond, British Delegation, Paris, 4 July 1919, H. Nicolson.

[9] LONA S699-700 My dear Nicolson, Sunderland House, London, 23 July 1919, E. Drummond.

[10] For the formative administrative practices, see: Gram-Skjoldager and Ikonomou “The Construction of the League of Nations Secretariat”.

[11] Thomas Smejkal “Protection in Practice: The Minorities Section of the League of Nations Secretariat, 1919-1934’, Columbia University Academic Commons (2010); Patricia Clavin Securing the World Economy: The Reinvention of the League of Nations, 1920-1946, (Oxford: OUP, 2013).

Images:

LONA S699-700, Geneva.

Campus of Anatolia College in Merzifon, early 1900s. Curtesy of: http://dspace.act.edu/jspui/handle/1886/301 (27.10.17)

Average length of first employment interval - Developed by Adam Finnemann with material from the LONSEA database, a part of Torsten Kahlert's ongoing postdoc project.