Gender Distribution in The League of Nations: The Start of a Revolution?

Myriam Piguet (master student - Aarhus University)

In 1920, the League of Nations officially opened its doors to both to women and men. But how exactly was this put into practice?

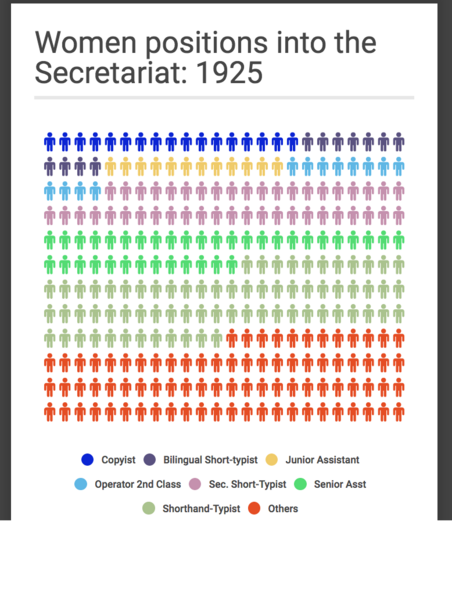

Two hundred and forty-five women were employed at the League Secretariat in 1925, predominantly working in the Central Services or as Secretaries. Miss Princess Radziwill was one of them, holding the grade of Senior Assistant (like 13% of the League’s female employees) in the Information Section. In February 1922, she wrote a letter to the Secretary-General of the League of Nations Sir Eric Drummond stating:

“While in no way protesting against my contract, I would like (…) to renew once more the protest I made (…) against the status of a certain number of women members in the Secretariat, whose work is akin to that of Member of Section, and who are grouped under the name of Senior Assistant (...) They are treated in a manner which seems to me to be out of proportion to their work when compared with that of other grades in the Secretariat.” (1)

Her words would resonate with any ambitious woman of today trying to reach a position with responsibilities in the private or public sphere, and hitting the ‘glass ceiling’. In the interwar period, however, such a statement marked something entirely new, as many national administrations, such as the United Kingdom Home Civil Service, still had their higher positions completely closed to women.

A unique step towards gender equality

From the outset, the League of Nations chose an innovative and distinct path, allowing women to be considered on an equal footing to their male counterparts in terms of positions. officially, no differences were made between the genders regarding hiring, promotions or dismissals. This was a pioneering decision taken at the creation of the League, owing much to the lobbying of feminist associations.

On the 10th of April 1919, a joint deputation consisting of the International Council of Women and the Conference of Women Suffragists in the Allied Countries and the United States was received by the League of Nations’ Commission at the Paris Peace Conference. Here they presented a petition urging “that women be equally eligible with men to the Body of Delegates, the Executive Council and the Permanent Secretariat and should be appointed to all the permanent Commissions on the same terms as men.” (2) It led to the addition of the following sentence to article 7 of the League of Nations’ Covenant:

“All positions under or in connection with the League, including the Secretariat, shall be open equally to men and women.” (3)

The statement was an important victory for the international feminists, and – it was hoped – represented the beginning of the end of the gendered bourgeois diplomatic practices, in place since the institutionalization of the profession in the 19th century. Traditionally, the wife of the diplomat tackled the soft-power part of the position without being granted her own salary. However, the activism of the international feminist movements was not the only driver behind the gender article of the Covenant. The changes were also pushed to the fore by deep ideological and economic forces.

Ideological, because considering internationalism without women’s right would have been nonsense. Women were already profoundly engaged in non-governmental peace movements and movements fronting internationalism and following the First World War they were increasingly drawn into the formal political sphere. Furthermore, the women of the League represented the perfect role model and participated in the creation and communication of a fresh and accessible aesthetic of international diplomacy. Economic, because the utility of women at work had been well proven during the First World War. The bureaucratic revolution of national (and international) administrations taking place in the interwar period, required a high number of feminine hands to tackle the humdrum secretarial work. Consequently, by 1925, women represented half of the League employees. Hence, at first glance, the League Secretariat appears to be an institution where parity between genders was protected and respected.

In practice, the gendered division remains

Through research done as part of my MA degree at Aarhus University, I have mapped the sociological profile of this first generation of women working in the League Secretariat during Sir Eric Drummond’s Secretary-Generalship (1919-1932) and aims at tracing their typical career paths. For the past months, I have been compiling data from the list of employees and biographical information from different personnel files, retrieved from the League of Nations archives in Geneva. Mixing a quantitative and qualitative approach, my results show, rather unsurprisingly, that the League of Nations wasn’t as gender equal as the Covenant proclaimed.

Women were mostly handling exclusively feminine positions with fewer or inexistent responsibilities, such as shorthand typist, copyist or secretary, and were mainly present in the Internal Administration Service. This service, which was central to the development of highly organized bureaucracy, was made up of different sections: The Pool – or Stenographic department – and the Dactylo Department were both overwhelmingly feminine and consequently led by two women, Miss Day and Mme Piachaud.

Only two years after beginning her work as Head of the Stenographic Service, which was the largest service of the League in terms of size of personnel, Julienne Piachaud, in a letter to Sir Eric Drummond on the 24th of February 1924, complained about not being considered equal to her male counterparts from the Roneo (stencil duplication) and Distribution Services. In fact, in 1929, she was only granted a salary of 16.250 Swiss francs, while Mr. van Ash van Wijck holding the same position as Chief of Service in the Distribution Department, received a salary of 19.000 Swiss francs.

Clear differences in salaries

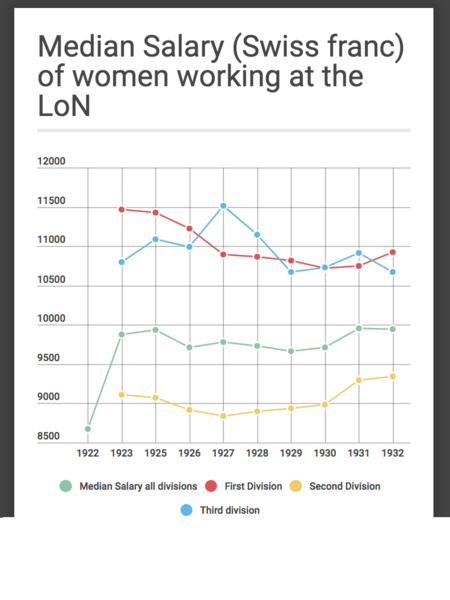

In general women were paid less than men for the same amount of work. The median salary for women, if taken all together, was 9.934 Swiss francs, way below the 12.000 Swiss francs of a Member of Section. This observation is, of course, reflective of the high number of technical positions, but if we only keep the 1% of women who were in high positions, such as Lady Blennerhasset, one of the few women English translators, or Dame Rachel Crowdy, Head of the Opium and Social Section, we reach the exact same conclusion: the median Salary was 25.667 Swiss francs, and thus below the one of a typical male Chief of Service starting at 28.000 Swiss francs.

Gendered division of Labour

Furthermore, we can observe a traditional gendered division of labour in the highest positions. Most women were covering areas directly related to women’s issues, archival work, children or social rights, and were kept far away from economics, direct diplomacy or questions of war and peace. An observation, which underscores that the old bourgeois vision of the women: naturally organized, kind, attentive, and pacifist, wasn’t yet completely out of fashion.

A Question of Education

It appears that finding women suited for the positions was a rather difficult task. Despite every post being equally open to both sexes, female applicants often had insufficient or the wrong kind of education for the position. Consequently, women had a hard time competing with their male counterparts, and those who landed higher posts often had rather atypical former work experience. Miss Schlesser, for instance, private secretary of Deputy Secretary-General Joseph Avenol, was previously the Assistant Director at l’Ecole de Haut Enseignement Commercial pour Jeunes Filles in Paris. A former position, which despite being far from her role of Secretary of the League, surely represents one of the highest levels of education a woman could reach in the interwar period.

Consequently, many women had good opportunities of advancement once inside the Secretariat. Miss Piachaud, for instance, went from Shorthand typist to Chief of Service in less than two years, despite her young age, and Miss Radziwill was granted the position of Member of Section, together with other Senior Assistants, in 1927. Although the differences in salaries persisted until League ceased to exist, women were represented in every Section and promotions were encouraged in the lowest rank (for instance from Shorthand typist to Senior Assistant). Their demands were, to some extent, heard – a slow administrative revolution in the making.

A revolution with its ups and downs

Sir Eric Drummond Secretary-Generalship marked the zenith of the League of Nations’ journey towards gender equality. With his departure, the escalating international tensions of the 1930s, and the discrediting of the League, the number of employees decreased steadily, and often, men replaced departing women, putting an end to this transformative development. Gender equality became a second-rate issue for the League of Nations.

But after all, every evolution is slow and characterized by ups and downs. During its golden age, the League of Nations took big steps toward female representation. It did truly open its doors to qualified women, and offered a new generation – one that was thrilled by the idea of joining men at work and serve the international ideals – the chance to take part in the establishment and development of the world’s first international administration.

References:

(1) Letter from Miss Radziwill to Sir Eric Drummond, 2nd of February 1922., League of Nations Archives, Section files, Personnel files, box s. 861: file 2950-2967. Sta.B.65/Shelf 56. file 2955.

(2) Egon F. Ranshofen-Wertheimer, The international Secretariat : A Great Experiment in International (Washington: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1945)