Edvard Hambro and the academic networks of international politics

Haakon A. Ikonomou (postdoc - Aarhus University)

This blog explores two broad academic networks and their impact on international politics by probing into the career and writings of the Norwegian jurist and diplomat Edvard Hambro. Both networks developed in close connection to the League of Nations, in the many institutions that surrounded and perforated it, and drove two transformative developments leading into the postwar years: First, the professionalization of foreign policy formation and the transnational process of introducing international relations as an applied academic discipline. Second, the emergence of an autonomous and legitimate field of international law, produced, in large parts, by heterogenic networks of international jurists.

In 1919, US and British delegates to the Paris Peace Conference agreed to establish a joint institute of foreign affairs. It became two: the British Institute of International Affairs (1920) and the Council on Foreign Relations (1921).

Child of a new Foreign Policy

The establishment of the League of Nations ushered in a period marked by the scientific search for new and better ways of managing international politics. Already at the Paris Peace Conference what would eventually become two highly influential research institutes – the British Institute of International Affairs (1920) and the Council on Foreign Relations (1921) – were first conceptualized. The League itself would ceaselessly co-ordinate and host workshops, conferences, lecture series and summer schools on international topics. The Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, co-founded in 1927 by two League officials, and the League’s International Committee for Intellectual Co-operation (ICIC) were two of the most important nodal points. Across Europe, national committees and institutes were created to fulfil the promise of a new diplomacy – so also in Norway.

Edvard Hambro was part of the highly influential foreign policy and academic network that clustered around the Nobel Institute, the Norwegian Committee for International Studies, the Chr. Michelsen Institute for Science and Intellectual Freedom (the first private research institute in Norway) and the University of Oslo. This network of institutions made up an “unofficial think tank and provider of premises for Norwegian foreign policy” in the first several decades of the 20thCentury.[1] They all worked to professionalize foreign policy making by institutionalizing international law and international relations as academic fields that should underpin political processes. The foreign policy-making process was to be expert-driven and multilateral.

The Nobel Institute: A real hub for the reinvention of international relations

Among the most central and senior actors in these networks was historian and political scientist Christian L. Lange, secretary of the Parliamentary Nobel Committee (1900-09); secretary of the Inter-Parliamentary Union (1909-1933); and winner of the 1921 Nobel Peace Prize, together with Hjalmar Branting, for his efforts as a Norwegian delegate to the League Assembly to push for comprehensive disarmament. Lange was also a correspondent and contact point for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and initiator to form the Norwegian Committee for International Studies (1936).

The network had strong ties to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and included such men as historian, peace activist and Labour Party Foreign Minister (1935-41) Halvdan Koht. Arne Ording was another leading figure, taking active part in the Norwegian Committee for International Studies and editing the popular-academic journal International Politics. In the postwar years he was in-house historian, éminence grise, and consultant to Halvard Lange (son of Christian L. Lange) – the longest sitting Norwegian Foreign Minister (1946-65). Another one was the jurist Frede Castberg: consultant to the Norwegian Nobel Institute in the early 1920s, and, from 1922 until his retirement in the 1960s, the MFA’s permanent international law consultant. Castberg was instrumental in establishing a department of political science at the University in Oslo in the postwar years, and linking this with the diplomatic academy of the Norwegian foreign service.[2]

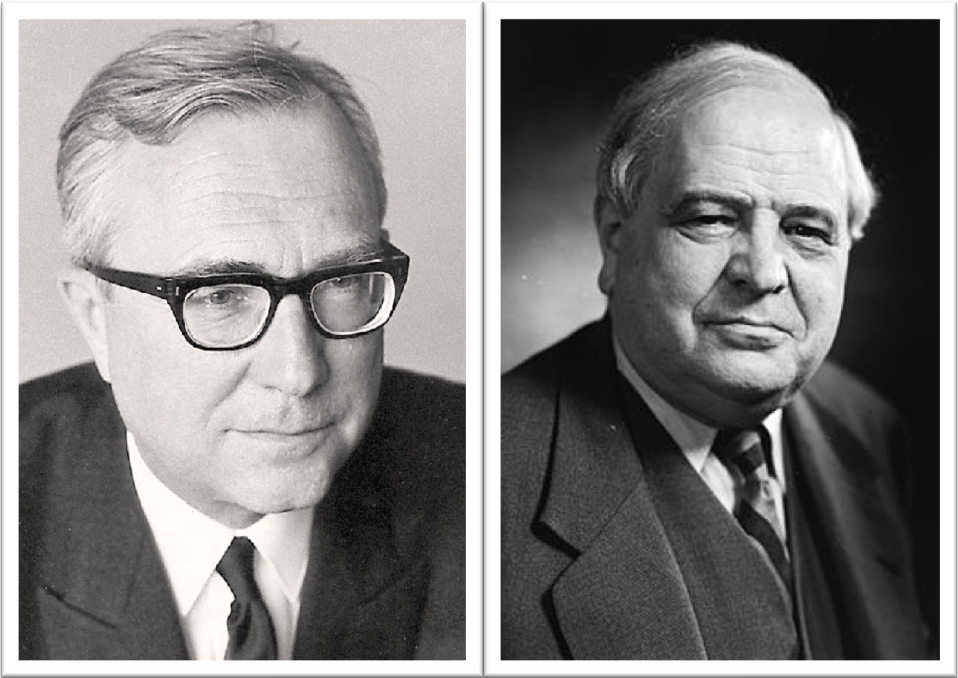

Son and Father: Edvard Hambro (left) and C. J. Hambro (right)

To these four, and many other protagonists, came the younger Edvard Hambro, son of Conservative politician, President of the Norwegian Parliament and chairman of the League Assembly’s mighty Supervisory Commission, Carl Joachim Hambro.

Orbiting the League

Hambro belonged to the vast group of academics, experts, activists, diplomats and politicians that orbited the League – bouncing between the outer and inner tiers circling the Genevan hub, through the many professional networks and institutions that were connected to it.

In 1929, Hambro finished his introductory degree at the University of Oslo, before completing a law degree in 1934. During those years, Hambro had his first experience with international cooperation, as he worked as a temporary collaborator with the Information Section of the League Secretariat during the 1933 Assembly and was employed in the service of the Saar Plebiscite Commission in 1934. Inspired by this, Hambro went on to take a doctorate in political science at the Geneva Institute in 1936. Following this, and equipped with a Rockefeller Grant, he studied and went on several fellowships in Europe and the United States, including an exchange to Yale University’s Department of International Relations.

At the same time, Hambro gunned for a post in the League Secretariat. In 1937, the Norwegian Hans Mohr, secretaire principal at the Section for Intellectual Cooperation in the League of Nations, wrote a strong letter of recommendation to the League on behalf of Hambro.[3] Director of the Information Section Adriaan Pelt took the request to Deputy Secretary General Seán Lester, but nothing came of it.[4] Instead, Hambro returned to Norway to head the International Department of the Chr. Michelsen Institute.

An internationalist’s career

After working for the Allied forces and the Norwegian Government-in-exile during the war years, Hambro would join the Norwegian delegation at the San Francisco Conference in 1945 and became the first director of the UN’s legal section. Between 1946 and 1953 he was the registrar at the International Court of Justice at The Hague.

The San Francisco Conference (1945): something borrowed, something new

After stints as a professor of law and as a Conservative member of Parliament, Hambro finished his professional career in the diplomatic trade. First, as Ambassador to the UN in New York from 1966 onwards, where he was chair of the General Assembly’s Legal Committee (1967), and also served as the president of the General Assembly (1970-71). Then, as Ambassador to EFTA, GATT and the UN in Geneva (1973-75) and to Paris (1976), a post he held only for a few months before passing away in February 1977.

Having taken active part in the League and the UN, Hambro could boast an unusually broad network of international jurists, which was very useful in his work for and with international law. Hambro was deeply engaged in human rights issues, and was, for example, an official observer for the High Commissioner of Refugees in Hong Kong (1954), and later for the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) to South Africa and Ethiopia. As an active member of the Institut de Droit Internationale, moreover, Hambro was – shortly before his death – elected its President, and was, had he lived on, to host its annual conference in Oslo in 1977.[5]

Expert-driven multilateralism

Hambro’s biography is important as it draws our attention to two broader international trends. First, in his efforts to ‘professionalize’ foreign policy as an object of study and practice, Hambro and his contemporaries, were part of a broader shift. The Royal Institute of International Affairs (London), the Council on Foreign Relations (New York), Centre d’Études de Politique Etrangère (Paris), and Institut für Aussenpolitische Forschung (Berlin), were predecessors and inspirations for the establishment of international relations as an academic discipline in Norway.[6] Historians Steine and Friis show similar institutional developments in Sweden and Denmark and that these developments were underpinned by financial support from Carnegie and the Rockefeller Foundation. Across the board, they worked for the establishment of international studies as an academic discipline, and for the proliferation of international law as applied science.[7]

Edvard Hambro was a crystal-clear proponent of this view. On the brink of the Second World War, looking back at the interwar period, Edvard Hambro reflected that “the ideal diplomat for our era must be equipped with sharp intelligence, an alert mind and psychological sense, besides vast and comprehensive knowledge in ethnography, history, legal science and economy. And it was fatal that so many of the negotiators in Paris in 1919 lacked a great many of these conditions.”[8]

This was because ‘old diplomacy’ was based on might, and conducted by Great Powers in secrecy. Reflecting on this in his 1943 “Small states and a new league – From the viewpoint of Norway”, Hambro wrote:

Norwegians […] do not feel that the Great Powers have shown such a degree of wisdom and foresight as would entitle them to be the trustees of the world. They feel — perhaps because they are from a small nation — that the only claim the Great Powers have to rule the world lies in their strength. And power — as the leaders of the great democracies have themselves so insistently declared — should not be the only basis of the world of tomorrow.[9]

Norwegians, according to Hambro, felt “that a balance of power [was] impossible in the future, and [was] convinced that the Concert of Europe cannot be recreated in the form of a “World Quartet”, referring to the Allied Powers (including France). “Those of a soberer cast of mind”, among which he clearly counted himself, had to search for the answers of a future world order in the experiences of the League of Nations.

To Hambro’s mind, the League represented “the most thoroughgoing and most ambitious effort at world collaboration yet attempted”, and after listing its achievements, he stated unequivocally: “it was not the League that failed, but the member states” as it was “bound to be unimportant if the states would not use it”. International organizations needed active participation from its member states and universal membership (the lack of the latter being the greatest shortcoming of the League). The interdependence of the world was “so obvious” for Hambro and his fellow Norwegians that they were “quite amazed that others do not recognize it in the same way”.[10] Only a foreign policy governed by expertise and science would make for sensible multilateralism and peaceful co-existence on the basis of international law.

The Gentle Civilizers

This brings us to a second international pattern. Hambro was an increasingly prominent part of a network of experts on international law that were crucial in articulating the idea that world peace was best secured through an international legal order with commanding courts. In the interwar period these networks clustered, among other places, around the Institut de Droit International, to work, in the words of the institute’s statutes, “for the triumph of the principles of justice and humanity”.[11]

Institute de Droit International received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1904 forwork for arbitration among States

Sociologists Guillaume Sacriste and Antoine Vauchez argue that a heterogenic network of legal scholars emerged from the 1890s onwards, and by the 1920s – through their contestations with bordering fields (such as politics, economics etc.) and amongst themselves – they had positively affirmed the existence of an international rule of law.[12] Equally, probing into the cases of the Briand project on a Federal Europe (1929-30) and the drafting and initial institutionalization of European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), legal scholar and sociologist Mikael Rask Madsen, together with Vauchez, emphasize the role played by transnational networks of international jurists in defining the European field of Human Rights as an autonomous legal field.[13] Unsurprisingly, therefore, Edvard Hambro, together with Frede Castberg, were among the most important proponents of Norway joining the ECHR and the European Court of Human Rights in the 1950s and 1960s.[14]

Gaetano Morelli presided of the Centenary anniversary of the Institut de Droit International. He was deeply influenced by the thinking of Dionisio Anzilotti, an early League Official and later judge of the Permanent Court of International Justice.

Hambro would highlight the importance of the international legal community himself, in an article written for the centenary anniversary of the Institut de Droit International in 1973. Here he determined that the Institute had played an important part in the development of international law, as “[t]he resolutions and debates are frequently quoted in the literature of international law and nearly always with approval” and “very often are to be found in the dissenting and individual opinions of the judges of the Court”. More important, however was the indirect influence of the members of the institute, seen as they were “among the most highly respected teachers of international law, judges and international civil servants”. “As a general rule, it must be stated that members and associates of the Institute are to be found wherever international law is applied or created,” Hambro proclaimed before concluding:

“It might be said with a word which is not very popular these days that the Institute forms the “establishment” of the international law community. The members meet and collaborate in so many capacities and in so many fora and in so many locations that they quite obviously influence each other and form a corporation with all the advantages and all the dangers inherent in this term.”[15]

International politics from interwar to postwar

Hambro’s life and thoughts highlight the intellectual and human overlap between the processes of professionalizing foreign policy and establishing international law as an autonomous field, and show how both were embedded in the far-reaching infrastructure in and around Geneva. Deep-seated institutional reforms of national MFAs came after the Second World War, and as a direct response to the mushrooming of second-generation IOs. Likewise, international law was catapulted onto the front-stage of international politics with the atrocities of the Second World War. Nonetheless, the seeds were sown in such political-academic networks and institutions, orbiting the League, as those Hambro belonged to in the interwar period.

References:

[1] B. A. Steine “Forskning og formidling for fred, 1900-1950” in Historisk Tidsskrift 02/2005, 260.My translation.

[2] https://nbl.snl.no/Arne_Ording(21.11.17); Steine “Forskning”; Frede Castberg Minner om politikk og vitenskap fra årene 1900–1970 (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1971); Øyvind Tønnesson “Internasjonalisten Christian L. Lange – representant for en norsk fredstradisjon?”,Historisk Tidsskrift, 84/2005, 311-324.

[3] LONA-S788, Hambro – Dear M. Krabbe – Paris, 26.01.1937 – Mohr; http://runeberg.org/hvemerhvem/1973/0387.html(23.11.2017).

[4] LONA-S788, Hambro – M. Lester – 2.04.1937 – Pelt.

[5] http://runeberg.org/hvemerhvem/1973/0205.html; https://nbl.snl.no/Edvard_Hambro; F. Seyersted, “Edvard Hambro - In Memoriam” 46 Nordisk Tidsskrift for International Ret 7, 8 (1977).

[6] E. Hambro, “Forskning og Fred”, Beretninger fra Chr. Michelsens Institutt for Videnskap og Åndsfrihet, Bind IX, Bergen: A. S. John Griegs Boktrykkeri, 1939, 5-6.

[7] http://projects.au.dk/inventingbureaucracy/blog/show/artikel/the-scandinavian-center-denmark-and-the-early-years-of-international-studies-under-the-league-of-na/(21.11.18); Steine “Forskning”, 271.

[8] Hambro, “Forskning og Fred”, 4.

[9] E. Hambro “Small states and a new league – From the viewpoint of Norway”, American Political Science Review, 1943, 909.

[10] Hambro “Small states”, 903-8.

[11] E. Hambro, “The Centenary of the Institut de Droit International”, 43 Nordisk Tidsskrift International Ret 9:17 (1973), 9. My Translation.

[12] G. Sacriste and A. Vauchez “The Force of International Law: Lawyers’ Diplomacy on the International Scene in the 1920s”,Law & Social Inquiry, 32:1 (2007), 83-107.

[13] M. Rask Madsen and A. Vauchez, “European Constitutionalism at the Cradle. Law and Lawyers in the Construction of a European Political Order, 1920-1960” in Lawyers Circles: Lawyers and European Legal Integration. Recht der Werkelikheid, 25:2004.

[14] A. Hareide “Norge og Den europeiske menneskerettighetsdomstolen. Veien fra motstand til tilslutning, 1948-1964”, MA-thesis, UiO, 2016.

[15] Hambro, “The Centenary”, 15-17. My Italics.

Images:

William Orpen “The Signing of Peace in the Hall of Mirrors, 28thJune 1919": https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:William_Orpen_-_The_Signing_of_Peace_in_the_Hall_of_Mirrors,_Versailles.jpg

Nobel Institute (1905): https://www.nobelpeaceprize.org/Organization/Building

Hambro and Hambro: https://nbl.snl.no/Edvard_Hambroand https://no.wikipedia.org/wiki/C.J._Hambro

United Nations: https://www.hoover.org/library-archives/collections/united-nations-conference-international-organization-proceedings-1945

Peace Prize (1904): http://www.idi-iil.org/app/uploads/2016/11/20170530_170331-e1497701920910.jpg

Morelli: http://www.idi-iil.org/app/uploads/2017/06/1971-1973-Gaetano-Morelli-Rome-1973-1.jpg