Re-carving as a sign of re-use: The case of a portrait in the Fitzwilliam Museum

By Nathalia B. Kristensen and Olympia Bobou.

Scholars have long argued that ancient urban centres were consumer cities, but the research project Circular Economy and Urban Sustainability in Antiquity: Comparative Perspectives from the Ancient World with a Point of Departure in Palmyra wants to show that self-sufficiency and reliance on materials from their surrounding areas (hinterlands) were characteristics of most ancient cities. Through the portrait reliefs used for sealing burial niches in the great family tombs, we can trace some of the mechanisms of Palmyrene economy, and demonstrate how circular economy functioned in the area of sculpture.

The Palmyra Portrait Project (2012-2019), has documented almost 4000 portraits, mostly coming from the funerary sphere, and dating from around 50 BCE to 273 CE, when the city was sacked by Aurelian’s forces. All of them were made of limestone from local quarries, of which three are fairly well published.

Most reliefs portrayed single individuals; both men and women were dressed in a tunic and himation. Furthermore, married women would wear multiple headdresses such as headbands, turbans and veils. Additional ornaments and details could be added to the portraits for a price – the more ornamentation, the more costly the object would become.

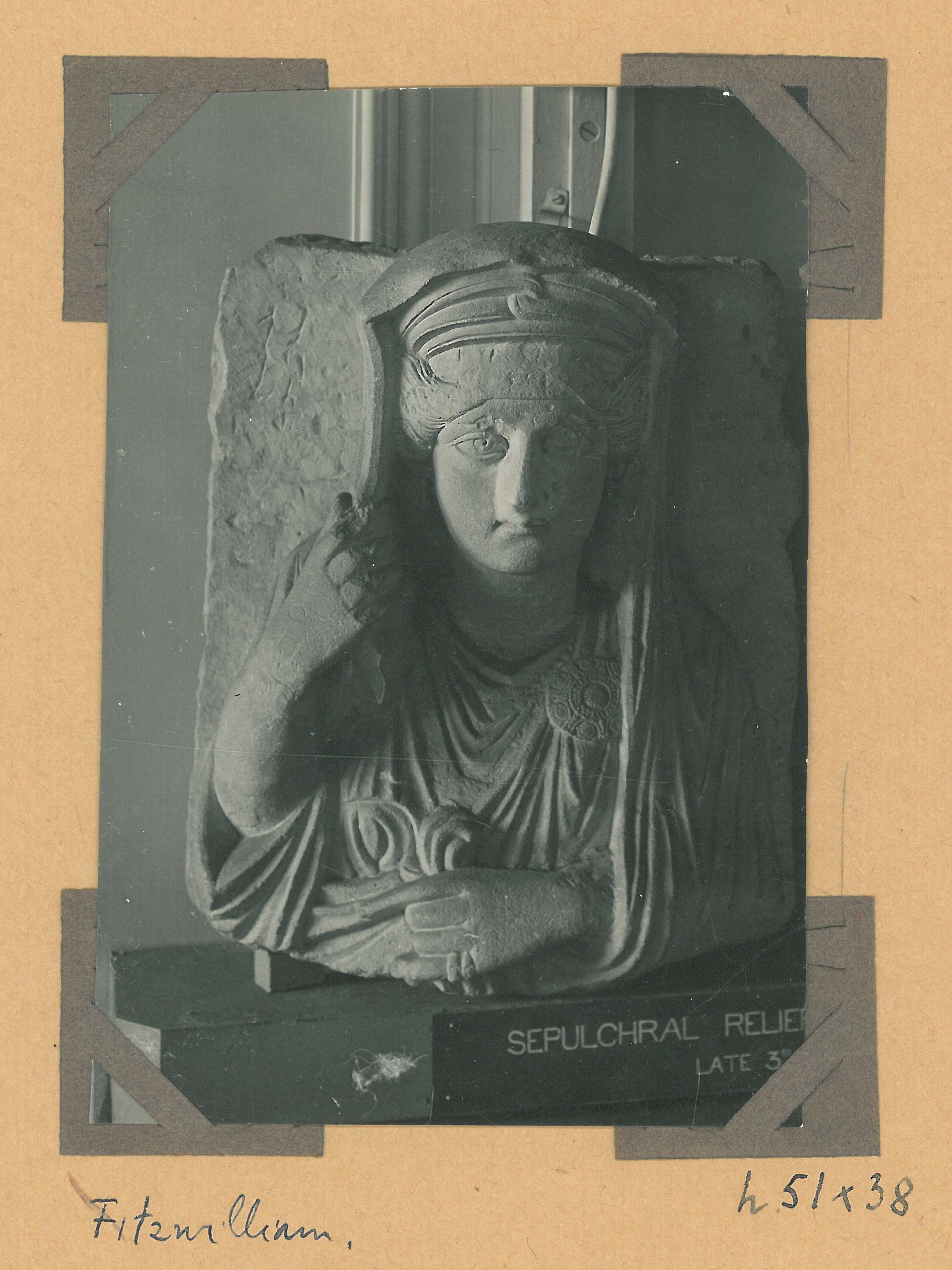

A portrait of a married women, now in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (inv. no. GR 8.1888), was depicted wearing a chain attached at the centre of the turban and running on either side of the head, three necklaces, two bracelets, as well as a circular brooch and two finger rings. An inscription was placed to the right of her head and would have likely informed us of her name and the name of her father and grandfather. On closer examination, it becomes clear that the head chain, the three necklaces, both bracelets as well as much of the inscription has been re-carved. The relief was never used as a commemorative funerary relief for the ornately decorated woman and in order for the carver to re-use the portrait, he removed many of the details such as the jewellery and inscription. This would make it less expensive and more likely to be resold.

We may not know why the original customer did not use the portrait relief, but the re-carving shows that even a fully finished object could be sold and resold until it could be used in its place in a tomb. Even though the limestone was quarried nearby and relatively cheap to acquire, it was still more financially sound to re-carve and re-use an object than to commission a new one. By looking at the degree of re-use in Palmyrene sculptures it may be possible for us to examine fluctuation and stability of Palmyrene economy.

Further reading:

Albertson, F. 2012. The ’Date’ on Two Dated Palmyran Funerary Reliefs, Zeitschrift für Orient-Archäologie 5, 250-270.

Budde, L. and R. Nicholls 1964. A Catalogue of the Greek and Roman Sculpture in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schmidt-Colinet, A. 2017. Die antiken Steinbrüche von Palmyra: Ein Vorbericht. Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft zu Berlin 149, 159–196.

Zuiderhoek, A. 2016. The Ancient City. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.