The Archaeology and Afterlives of Palmyrene Sculpture

By Postdoc Amy C. Miranda.

The lives of objects do not stop at their creation or even the end of their use. The funerary banquet relief of Bar’ateh and his family lived its Palmyrene life until the sack of 273 CE, but found new life after its excavation in the later 19th century. The Ingholt Archive shows how Palmyrene funerary sculptures tell stories of the more recent past, with the potential to shed light on modern archaeological and museological practices as well as cultural heritage preservation.

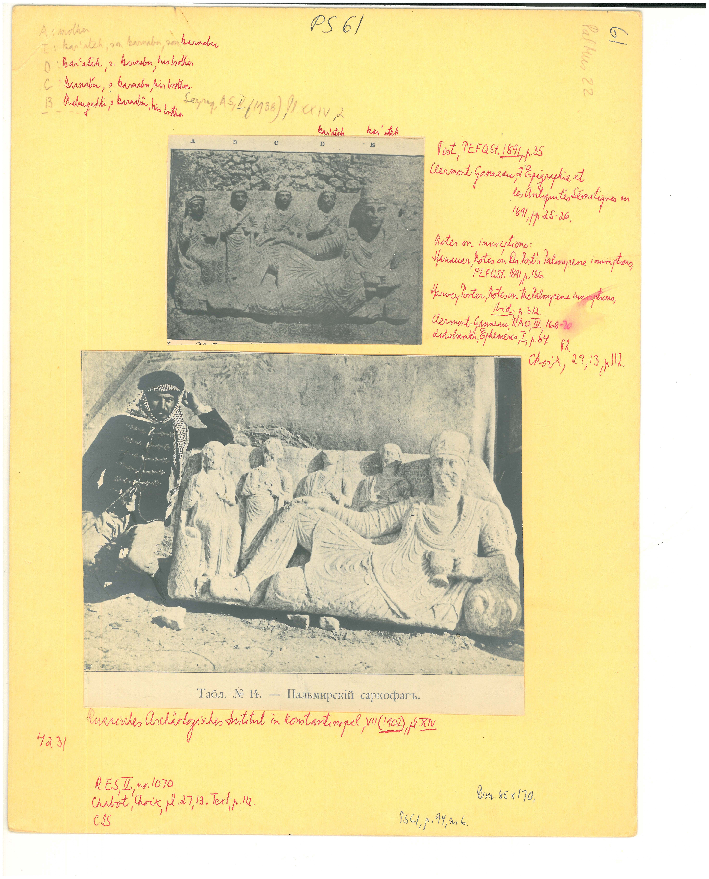

The yellow sheet of Palmyrene Sculpture 61, abbreviated as PS 61, features two different images of a relief sculpture and copious notes in red ink. (Fig. 1) There are five separate sheets that document PS 61, but the example shown is, perhaps, most representative of the group.

There are five figures on this sarcophagus lid, with Bar’ateh, the patriarch, as the reclining figure at the viewer’s right. The others are ʿAtemâ (at the viewer’s left), and three male figures: Bar’ateh, Barnebu, and Nebogaddai. The relationship of these figures to the first Bar’ateh is unclear and posed difficulties for Ingholt, and, as such, he has proposed two different family trees (Ingholt 1974, 40-43). The notes in red pen strewn across the page reflect Ingholt’s interest in the inscriptions and Palmyrene genealogy. However, it seems that the relief itself has had an exciting “afterlife.”

A telling moment in the afterlife of the sculpture is seen in the lower image on the archive sheet. Here a man in contemporary dress poses with the sarcophagus lid. The image was published by the Russkij archeologiečskij institut v Konstantinopole in 1902. (Russkij archeologiečskij institut v Konstantinopole, VII (1902), Pl. XIV) The RAIK operated from 1895 to 1914 when it ceased operations due to World War I (for more information about the RAIK, see Üre 2014.) During its period of activity, the RAIK was a formidable presence in the archaeology of the Middle East. The photographs in the publication as well as those taken by Ingholt show the sarcophagus lid in a better state of preservation than in a publication of 1997. (al-As'ad and Gawlikowski 1997, 68, cat. 104, fig. 104.) It seems that between 1902 and 1997 the sculpture underwent damage of which there is no documentation.

When Ingholt saw and photographed the sarcophagus lid it was not at the turn of the century, but in the 1920s as he was composing his doctoral thesis. The sculpture was still in Syria, but now at the Palmyra Museum. This adds another layer of intrigue to the sculptures’ story as, almost a century later, it was part of the museum’s collection during the systematic destruction of Palmyra in 2015.

One of the missions of the Palmyra projects based at Centre for Urban Network Evolutions (UrbNet) headed by professor Rubina Raja is cultural heritage preservation. Earlier this fall, an online list of cultural heritage resources was published here. Particular to the Archive Archaeology project, funded by the ALIPH Foundation, two of its major objectives are related to cultural heritage preservation:

(2) to assess damages and losses of Palmyrene cultural heritage based on the primary evidence collected in the unpublished archive and the diaries

(3) to reconstruct lost and damaged contexts based on the evidence collected in the archive

https://projects.au.dk/archivearcheology/about/

As such, Archive Archaeology will offer access to lost Palmyrene heritage. Many objects in Ingholt’s archive were affected by the war in Syria, and PS 61 is just one example of the way these objects touch different historic moments and cultures.

As field archaeologists recover, document, and analyse material found during survey and excavation, so too does archive archaeology. Although it is without physical survey and excavation in the traditional sense, archive archaeology digs layers of material to uncover the more recent past. The Archive Archaeology project is focused on recovering, documenting, and analysing Harald Ingholt’s archive of Palmyrene sculpture, began in the 1920s and donated to the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in 1983, with the goals of disseminating archival material and critically appraising the meaning of archives.

The Ingholt Archive is rife with potential, an as of yet untapped resource for scholars interested in Roman sculpture, the archaeology or the ancient Near East, early 20th century collecting practices, and cultural heritage preservation to name but a few examples. The Archive Archaeology team looks forward to seeing the myriad research directions in which this material can go.

More about the project is available at https://projects.au.dk/archivearcheology/

Further reading:

- The Palmyra Portrait Project website

- Raja, R. & A. H. Sørensen (2015). Harald Ingholt & Palmyra (English version), Aarhus.

- Raja R. (2019). Catalogue: The Palmyra Collection, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

- Raja, R. (2019). “Harald Ingholt and Palmyra.” In R. Raja & A. M. Nielsen (eds), The Road to Palmyra, Copenhagen, pp. 41-64.

References:

- al-As'ad, K. & M. Gawlikowski (1997). The Inscriptions in the Museum of Palmyra. Warsaw.

- Ingholt, H. (1974). “Two Unpublished Tombs from the Southwest Necropolis of Palmyra, Syria.” In D.K. Kouymjian (ed.), Near Eastern Numismatics, Iconography, Epigraphy and History, Beirut, pp. 37-54.

- Üre, P. (2014). Byzantine Heritage, Archaeology, and Politics between Russia and the Ottoman Empire: Russian Archaeological Institute in Constantinople (1894-1914). PhD thesis, The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).