Film-splaining the League of Nations

Helle Strandgaard Jensen (Associate Professor - Aarhus University) and Nikolai Schulz (Head of BUSTER School and Family Programme - CPH PIX)

In 1937 the Warner brothers’ The Life of Emil Zola won the Oscars and was praised by The New York Times for being “the finest historical film ever made”.[1] When cinemagoers went to see The Life of Emil Zola they might have learned about the work of the League of Nations. Not because the Warners' or Zola were connected to the League, but because it was the same year that the League’s infomercial The League at Work was produced. In the 1930s it was common to have such infomercials or newsreels playing before the feature films, one of which might have been the Warner brother’s Oscar winner.[2] In this blogpost we will review The League at Work and how it presented the League to a 1930s audience.

Opening titles to The League at Work: http://webtv.un.org/watch/the-league-at-work/4489134906001 (02.01.2018)

Infomercials were short documentaries shown as opening acts for the popular feature films. One of the best-known British infomercials is Night Mail, directed by Basil Wright and Harry Watt.[3] Allegedly, this short documentary from 1936 about the Royal Mail train delivery service, together with Wright’s The Song of Ceylon produced for the Ceylon Tea Propaganda Board in 1934, marks the height of the British documentary film movement.[4] After making Night Mail, Wright left the Film Unit subdivision of the UK General Mail Service to make his own production company, The Realist Film Unit (RFU).

In 1936-37 the League of Nations hired RFU to make an infomercial about the League.[5] The League at Work became its official title.

The purpose of The League at Work

In the well-preserved, two-part, archived version of the infomercial all the participants speak English and the voiceover is in English too.[6] However, as the League was a bilingual organisation a French version is likely to also have existed.

It is difficult to establish exactly where and how The League at Work was distributed, as sources surrounding the production of the film are scarce. However, as import and export of films were extremely elaborated at this point, and the League had a good distribution network for its general communication, a vast-spanning distribution is not unlikely to have brought it around the world.

A picture from the information documentary The Song of Ceylon

: sensesofcinema.com/2012/feature-articles/to-experience-song-of-ceylon/ (02.01.2018)

The aim of information documentaries such as Night Mail, The Song of Ceylon and The League at Work was to promote the institutions, which had paid for them. They informed about the institutions’ work and its relevance to cinemagoers. As such, the infomercial about the League fits well with the fare-ranging publicity strategies already in place at this point in time, as mentioned in a previous blogpost.[7] In the case of The League at Work, the institution’s many activities are framed as relevant because they all support the League’s overall goal – peacekeeping.

“Judge it for yourselves”

The importance of the work done by the League of Nations was stated upfront. Immediately after the title information, viewers are shown pictures of crosses and war memorials from Flanders. A voiceover tells us about the League’s aim to prevent war from happening again by making an open and just relationship between nations possible. The voiceover’s claims are supported in the next shot, where United States’ president, Woodrow Wilson, is seen, seemingly discussing the League, while a voiceover explains how the organisation is set up to improve and strengthen the relationship between the worlds’ nations.

The introduction ends with a call: “…though this idea [of peacekeeping] may not be new, it has never been tried at such great a scale before. Here is the League of Nations at work, judge it for yourselves.” This explicit invitation to judge the organisation invites the viewers to critically engage with the film and its content. The openness towards the viewer’s views is somewhat surprising. Contrasted with The Song of Ceylon and Night Mail, the viewers of The League at Work were not positioned as someone who should sit back and passively take in the information offered, rather she was a viewer who, in theory, had the right to judge and assess the quality of the work done at the League.

Nevertheless, judging by the content of the rest of the film, we might attribute this openness to the self-confidence of the organisation. Though the League by 1937 carried little weight as an arena to solve matters of high politics, The League at Work conveys a strong belief and confidence in the organization’s bureaucratic capacity as a global technocratic body solving all kinds of issues, big and small.

A smooth-running, fair, efficient and abstemious machine

The League at Work shows The League of Nations as a smooth and efficient machine, where important men make important decisions assisted by neatly dressed women. As noted in another blogpost, the Internal Services is the first section shown in the film.[8] The prominent place of this section in the film helps to build a narrative about the League as central, and relevant, to the entire world community, as this section contained the organisations’ postal services, translations and print activities. The scenes from the Internal Services show us that from Geneva, the world was connected, organised and analysed. A later sequence about the Information Section confirms this narrative, as we get to see how the League host journalists from world-leading newspapers, broadcasts in English, French and Spanish, and publishes a wide range of pamphlets, reports and books.

The Machinery at Work (mostly women as we can see): http://webtv.un.org/watch/the-league-at-work/4489134906001 (02.01.2018)

Other parts of the film clearly expand and elaborate on this well-polished image of the League, as when we hear from the treasurer that “the Leagues finances are sounder than ever”, assuring the viewers that the money their national government pays to its upkeep are well taken care of. Equally, when we hear about the legal section, we are assured of the Leagues efficiency, as it is mentioned that 4068 treaties have been published to date by the League. And when we hear about the mandate system, we are assured of its fairness by way of complicated calculations. Thus, when cinemagoers were invited to judge the League, they had all the arguments for its efficiency, its fairness and its abstemiousness.

Aesthetics and the use of cutaway scenes to loosen up the League

The invention of sound film was in some ways a throwback for the experimental and playful aesthetics that had marked filmmaking in the 1920s. The heavy equipment needed to record sound meant that the camera had to stand still, otherwise the sound of moving it around would predominate everything else. Thus, the experimental style of the 1920s-avant-garde film was replaced by films that seemed very still and dull in comparison, as filmmaking moved into the 1930s. Many of the scenes from inside the buildings in Geneva in The League at Work are marked by this style, giving The League at Work an outlook, which might be quite uninspiring from a contemporary perspective. Nevertheless, there are a great number of cutaway scenes (the interruption of a scene with the insertion of another scene) with voiceover in the film that help to loosen up the very serious and ‘still’ feel of the scenes from Geneva.

The cutaway scenes in The League at Work often help to further elaborate or explain the action of the different sections or committees. In some of these scenes, we see pictures from exotic places with palm trees and desserts, as we are told that the League cares about people everywhere. We see moving pictures of horse carriages and artillery from the First World War that are replaced by a shot that pans over the dead bodies of a mother and a child, reminding us why we need disarmament. Later again we see scenes from shady streets with even shadier hotels and junkies hooked on opioids to make us aware that the League also combats evils in big cities, not only in faraway places or on a geopolitical scale.

The scene that will give you Goosebumps

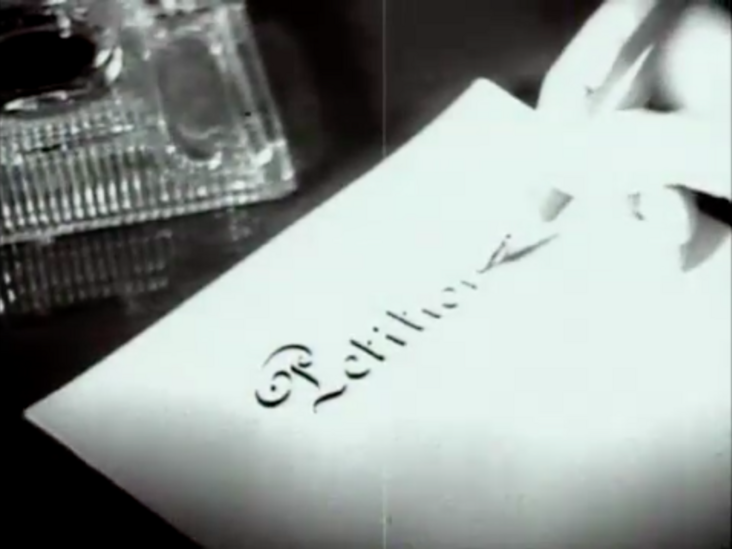

“Petition” meticulously written as a heading: http://webtv.un.org/watch/the-league-at-work/4489134906001 (02.01.2018)

Audio-visual sources convey history in different ways than written documents: as we hear the voices and see the images from the past, they seem to draw us ‘back in time’, and make distant events seem close and current. At the very end of the first of the two preserved reels, about nine minutes into the film, the voiceover tells us about the League’s effort to protect the rights of minorities. Form a present-day perspective, knowing how this failed at this point in time and still fails today, hearing about these visions and dreams for a safe and just world have the force to reach across 80 years in an instant, as the voiceover says: “…[m]inorities have been guaranteed civic rights, they are protected against unfair discrimination, which national or religious feelings might cause. Any person or group has the right to apply for protection. Their petitions are submitted to special committees. If these fail to obtain redress, the council takes action. Thus, the league works for mutual understanding and tries to prevent outburst of national feelings, dangerous to the peace of the world.”[9] Thus, while the stifled aesthetics and rather didactic style that marks most of The League at Work can seem rather unappealing to a modern-day viewer, the infomercial conveys the Leagues’ idealism with a great force that comes across very clearly even today.

References:

[1] Frank S. Nugent, “The Life of Emile Zola,” The New York Times, August 12, 1937.

[2] Luke McKernan, “A History of the British Newsreal,” by posted as pdf-file at British Universities Film & Video Council; History; British newsreels, http://bufvc.ac.uk/newsonscreen/learnmore/history (02.01.2018).

[3] Ian Aitkin, blogpost at BFI Screenonline; Night Mail (1936), http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/530415/ (02.01.2018).

[4] Ian Aitken, The Documentary Film Movement: An Anthology (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998). At the Brussels International Film Festival of 1935 A Song of Ceylon won first place in the documentary class, and the ‘Prix du Gouvernement’ for the best film in all classes.

[5] The videos held in UN Web TV archive which dates the films to 1935, but Wright’s company was not formed until 1936 and in Seán Lester’s biography The Guardian of a Small Flickering Light (by Marit Fosse and John Fox, Hamilton Books 2016), it is mentioned that Lester took part in making the film, p. 149.

[6] The League at Work, Reel 1 and 2. Available online at UN Web TV http://webtv.un.org/watch/the-league-at-work/4489134906001 (02.01.2018).

[7] Emil Eiby Seidenfaden, “L’esprit de Genève 2016 – Or: My First Meeting with the Archives of the United Nations Office of Geneva,” blog post at Invention of International Diplomacy blog. http://projects.au.dk/inventingbureaucracy/blog/show/artikel/blog-entry-by-emil-eiby-seidenfaden/(02.01.2018).

[8] Haakon A. Ikonomou, “An international language: The Translation and Interpretation Service,” on the Invention of International Diplomacy blog. http://projects.au.dk/inventingbureaucracy/blog/show/artikel/an-international-language-the-translation-and-interpretation-service/ (02.01.2018).

[9] The League at Work, end of reel 1.