A conference to remember

Haakon A. Ikonomou (postdoc - Aarhus University) - with Conference Summary by Professor Giles Scott-Smith (Leiden University)

On 24-26 November 2016, the Invention of International Bureaucracy project co-organised and participated in the New Diplomatic History Conference in Copenhagen. The full programme can be found here: http://cemes.ku.dk/newdiplomatichistory/

Some three years ago, while I was teaching at the University of Copenhagen, I had the idea that the 2nd Conference of the New Diplomatic History Network should take place in Copenhagen. The 1st NDH Conference, held at Leiden University in 2013, was the first major conference where I presented findings from my PhD from the European University Institute, concerning Norwegian diplomats and the first enlargement of the European Communities in the early 1970s.

I was rather anxious, and perhaps a little nervous, to hear what others had to say. Luckily, the panel discussion turned out to be both a rewarding and a pleasant experience. In fact, the conference was my first experience of belonging to a scholarly community. Even though no one dared to define what New Diplomatic History was (which is perhaps still the case), it was, and is, something – and I felt that I was at home.

Following that conference, the idea of a second conference remained vague, until I started teaching at the University of Copenhagen, and realized that I shared an office with another diplomacy buff – Dino Knudsen. Together we developed the idea of a ‘Danish chapter’ of the New Diplomatic History Network, and with the support of the SAXO Institute, we were able to host a string of network meetings and a concluding workshop. Here, at the final workshop, I remember we had the great pleasure of hearing Professor Giles Scott-Smith – who had organized the first NDH-conference – give an inspired keynote lecture on the character of the Honorary Consul.

At this point, in 2015, Dino and I felt ready to take the next step – and get the NDH-conference to Copenhagen. We gathered a strong team of scholars - Giles Scott-Smith (Leiden University), Karen Gram-Skjoldager (AU), Marianne Rostgaard (AAU) – secured funding, and set the date for 24-26 November 2016.

In the meantime, in August 2016, I started my new postdoc at Aarhus University (AU). My project will take on the Disarmament Section of the League of Nations Secretariat. The first few months, until Christmas, flew by: secondary literature, learning how to administer a blog, archival missions, and preparing the New Diplomatic History Conference and a paper for one of the panels.

With Karen Gram-Skjoldager and myself as co-organisers, then, it is unsurprising that the Invention of International Bureaucracy research group went all in at the conference. Emil Seidenfaden took part in a Round Table on ‘the public and diplomacy’; Karen and I presented a paper, and chaired several panels; and Torsten Kahlert took active part in the conference too. Indeed, the conference was a great opportunity for the team to get to know each other better (as only conference dinners and additional beers can do). A real joy and highly productive.

A month or so after the conference, Professor Giles Scott-Smith, one of the founders of the New Diplomatic History Network, wrote an enlightened summary of the conference for http://newdiplomatichistory.org, with offset in the three excellent keynotes on the programme.

What follows is his summary:

“In November the NDH network took its conference to Copenhagen for the follow-up to the inaugural gathering of the network at Leiden university in 2013. Once again, the three-day event demonstrated how rich and varied the current state of the field really is. Framed around three top-level keynotes, the conference consisted of 14 panels and a roundtable on social media and diplomacy. Speakers came from universities in nineteen different countries, and, encouragingly, the appeal of the network’s theme was confirmed with the attendance of many younger scholars and PhD students.

From left, Noe Cornago, Iver Neumann, and Geoff Pigman. From left, Noe Cornago, Iver Neumann, and Geoff Pigman.

From left, Noe Cornago, Iver Neumann, and Geoff Pigman. From left, Noe Cornago, Iver Neumann, and Geoff Pigman.

The keynotes set the tone for the three days, and I will concentrate on them for this report. Iver Neumann (LSE) provided the perfect start on Thursday with a perspective on the evolution of diplomacy. Noting that evolution is often seen as a loaded term of overweighted significance, Neumann argued for applying the notion of ‘tipping points’ (a term used in sociology since 1958 but which has the most application in climatology) and the identification of ‘punctuated equilibria’ (Eldridge & Gould, 1972) to designate moments when behaviour changes in fundamental ways. Placing this on to the development of diplomacy reveals key moments such as the development of complex polities, the arrival of permanent representation (not Renaissance Italy but the official contacts between Eastern and Western churches from 292AD onwards), the emergence of diplomatic systems, and institutionalism (forms of multilateral governance). The lecture generated some good debate, notably on the fact that evolution has not progressed linearly at the same speed but has seen many off-shoots and dead-ends (can we also see this in diplomatic practies?), and over the wider influence of technology as a decisive tipping point. Central to Neumann’s overview is the idea of progressive change, since tipping point in a climatological sense indicates a minor alteration that leads to an irreversible change in the system as a whole. Does diplomacy really evolve in those terms?

Geoff Pigman giving the keynote.

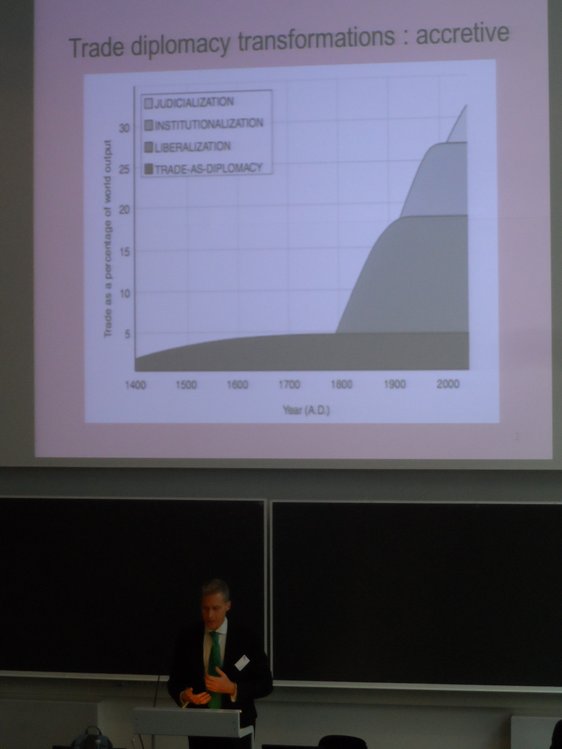

On the Friday Geoff Pigman’s keynote, entitled ‘Go Big or Go Home’: The Challenge for Trade Diplomacy in Europe and Worldwide, provided a perfect follow-up to the evolutionary opening of Neumann. Taking the starting point to be trade-as-diplomacy, Pigman traced a series of transformations as trade interactions adapted to and in turn altered the international environment in which it was operating. This took us through the industrial revolution (as the moment when the need for trade, due to the excess of goods, exceeded mere trade for diplomacy) and the first trade liberalization treaties (dating back to the Anglo-French Cobden-Chevalier Treaty of 1860). Institutionalisation followed, with the 1902 Brussels Sugar Convention (that opposed the use of export subsidies) as a key marker, leading to the creation of GATT after WWII and the progressive locking-in of gains from free trade over time, and for an expanding community of participating nations. This ceded to the era of judicialisation, exemplified by the WTO’s dispute settlement system and the application of trade laws above the jurisdiction of the nation-state. Yet this era has been relatively short-lived, since the collapse of the WTO’s Doha Round in 2015 has signaled a new shift towards the arranging of trade deals outside of the major sites of post-WWII multilateralism. The Silk Road project led by China is a perfect example, with trade as diplomacy being focused along a specific vector, in so doing reviving the old trade routes of the past. This adds an interesting counter-point to the evolutionary argument, since it points towards diplomatic change as being circular rather than linear (and this also being highlighted through non-Western initiatives).

On the Saturday Noe Cornago of the University of the Basque Country rounded off the event with an intriguing investigation into the ‘diplomatic incident’. These happen everywhere, and while they can represent different levels of seriousness, they all indicate some form of contravening diplomatic practice and protocol. The only title devoted solely to this issue is Bely’s L’Incident diplomatique (2010), which nevertheless begins with the deflationary comment that ‘An incident is by definition not so important.’ Diplomatic incidents can often be seen as trivial, anecdotal, and semi-humourous, but at the same time they may well represent critical events that could have led to war. Their ultimate meaning therefore remains inconclusive, and while they may seem like fleeting moments, they hold a long history as a distinct category. Political Science has developed various models for describing the sequence of events that take place during a crisis, and this approach has fed into Event History Analysis. But this approach only treats diplomatic incidents as international crises, leaving aside the apparently more minor triviata that nevertheless still can be accorded that title.

It is the role of the historian to create a narrative of what happened in ’the past’, and diplomatic incidents can, after some examination, be identified as having collectively shaped the diplomatic system itself. International law recognises diplomatic incidents as moments of transgression of norms and formal rules that have been accumulated over time, such as concerning rank, protocol, reciprocity, immunity, and so on. Cornago then went on to provide a series of examples for when such transgressions occurred, ranging from Ben Franklin refusing to wear ambassadorial uniform when in Paris, to de Gaulle’s ebullient but misjudged ‘Vive le Quebec Libre’ from 1967. Other incidents indicate more serious cleavages in the intricate patterns of diplomatic norms, such as the repeated discrimination against African diplomats and statesmen in the segregated US South during the 1950s and 1960s, and the storming and occupation of embassy sites by mobs, most notably the US Embassy in Tehran in 1979 and the ensuing holding of hostages. In this way incidents force the diplomatic system to respond ‘in order to ensure its own sustainability. As Bely put it, ‘incidents make transparent the relationship between the diplomat (in closed universe) and the society in which they operate’.

Cornago’s keynote was the perfect closure to the conference, because it was not a closure at all – instead, quite deliberately, it raised essential questions concerning the ways in which diplomatic practice (and diplomatic studies in turn) maintain their ‘shape’ while faced with constant tensions and threats to their established behaviour. This summed up the conference well – diplomatic studies as a field is facing an excess of approaches and perspectives, fuelled by innovative cross-disciplinary studies from the humanities and the social sciences. The New Diplomatic History network represents one of the few sites where these kinds of studies are encouraged to interact and exchange ideas. As a ‘state of the field’ event, Copenhagen therefore gave every reason for optimism. What needs to be considered next – as I mentioned at the opening of the event – is the extent to which the NDH network itself needs to define what it is about. Perhaps the network itself has reached a tipping point and should evolve in new directions. With this important thought in mind, I would like once again to thank my Danish colleagues for making the Copenhagen event possible: Karen Gram-Skjoldager, Dino Knudsen, Haakon Ikonomou, and Marianne Rostgaard.”

Sources:

http://newdiplomatichistory.org

http://cemes.ku.dk/newdiplomatichistory/