“Utterly below Criticism” – Working Conditions in the Palais Wilson 1930

Karen Gram-Skjoldager (Associate Professor - Aarhus University)

When tourists visit Geneva today, many go to see the Palais des Nations. You can understand why. The former headquarter of the League of Nations is a stunning construction that sits on the outskirts of the city in Ariana Park with beautiful views of Lake Geneva and the French Alps. The product of five different architects, the Palais was the first major purpose-built headquarter for an international organization, and at the time of its creation, the second-largest building in Europe, superseded only by Versailles.

Palais des Nations today – Photograph: Karen Gram-Skjoldager

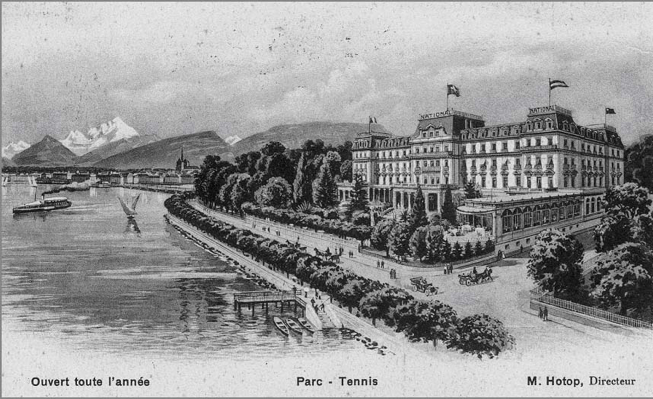

However, the construction of the Palais des Nations was not completed until 1936. For the majority of the League’s existence the organization held much more modest quarters in the former Hôtel National in central Geneva. Constructed in 1873-75, the five-storey, 225-room hotel by Lake Geneva was essentially the only available building in Geneva big enough to house the new international organization when it moved to Switzerland in 1920. In this blog, we shall have a look inside the hotel – renamed Palais Wilson in 1924 – to see what working conditions were like for the League’s staff as they were going about their daily business of preparing meetings, compiling statistics and typing up reports.

The Hôtel National when it was still one of Geneva’s most luxurious hotels (http://www.philameyrin.ch/b216.htm)

Fundamentally, the old hotel was not particularly well-suited for administrative functions and as the League’s work picked up pace, the leadership of the League Secretariat was struggling to fit the growing number of staff, meetings and conferences into the former hotel. For most of the League’s life, then, its staff worked under far from glamorous conditions, crammed together in small hotel rooms unfit for office work and in a number of improvised extensions and private homes around the old hotel. A report by the League’s medical adviser, Dr. Léon Weber-Bauler, who inspected the buildings in 1930, allows us a fascinating glimpse into this world at a time when the League was at its pinnacle with a staff approaching 700. In the following we will travel back in time and do a tour of the building with Dr. Weber-Bauler.

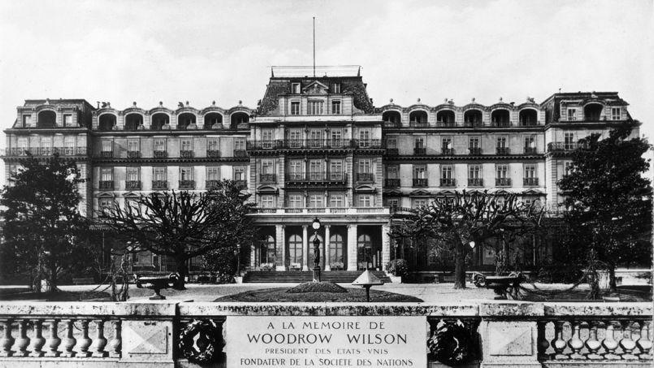

The Hôtel National after it had been renamed Palais Wilson in honour of American President Woodrow Wilson in 1924. (http://www.lefigaro.fr/histoire/centenaire-14-18/2014/11/10/26002-20141110ARTFIG00256-la-societe-des-nations-une-erreur-de-raisonnement-1919.php)

We enter the building through the lobby on the ground floor and start by ascending to the offices on the 1st to 3rd floor at the front of the main building, facing Lake Geneva. These offices are the old hotel’s most luxurious rooms. They are spacious and well-lighted with sinks and lavatories, as well as sound-proof double doors. Nearly all rooms have fireplaces which provide for excellent ventilation of the rooms. These hotel-rooms-turned-offices are taken up by the higher League officials and their staff.

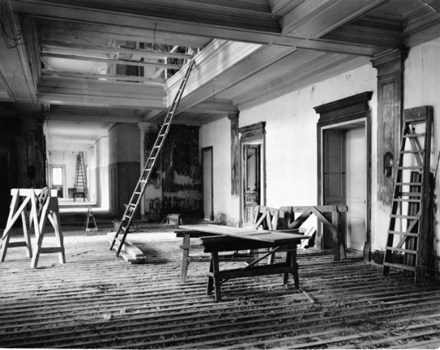

Renovation of the great corridor on the first floor of the main building. The offices on the right were to become the offices of the Secretary-General, Sir Eric Drummond. (www.indiana.edu)

However, even here, in the spacious quarters of the highest echelons of the League, it is apparent that the old hotel is short on space. On the 1st floor, for instance, a little closet by the service lift is being occupied by two short-hand typists, and in the lobby the main switch-board has been fitted into a small room at the end of a narrow, wooden spiral staircase. Dr. Weber-Bauler describes the working conditions of the operators to us: “in this low, cramped, gloomy and ill ventilated inferno they do work which is both physical and mental in a manner that astounds the visitor. Such pshyco-physical acrobatics should be performed in an airy well-lit and spacious room.”

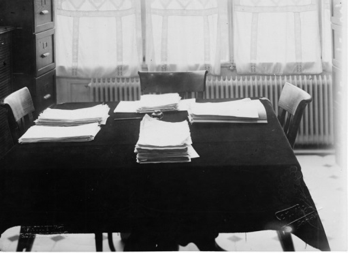

The library room by the Secretary-General’s office (www.indiana.edu)

We move on to the wings of the Palais. Here, the rooms are still of a decent quality but smaller, darker and sometimes overcrowded. Officials in the Health and Information Section in particular “occupy very small rooms in which nearly all the space is taken up by tables, cupboards and shelves.”

Interior of the Palace Wilson (www.indiana.edu)

However, this is nothing compared to the offices we see when we enter the attics. Here rooms are very small, badly lit and so overcrowded that in one of them staff “can hardly find room for their work-tables”. They are reached by a wooden stair-case, which is also the only escape route from the attic in case of a fire, and they are placed directly under a zinc roof and for this reason “excessively hot” during summer and cold during winter.

One room in the attic “faces a chimney one meter away from the window, and the kitchen chimney sends its combustion gases into the room when the windows are open”. Because of this, one former employee “developed specific anaemia, probably due to chronic carbon monoxide poisoning”.

Before we leave the main building, we go back to the corridor on the ground floor and descend into the basement, which appears to be even more unsafe than the attic. The basement is occupied by the kitchen, a restaurant, a library, a warehouse for documents, a dispatch service and a storeroom. “Incongruently, an engine-room with its stocks of wood and coal, placed in the middle of the passage, spreads heat, dust and noxious gases all around […] Its gaping boilers belch forth the gases from the clinkers taken out of its furnaces, straight into the main corridor on which all the rooms already mentioned open, including the restaurant!”

The dispatch service, seen here in somewhat more pleasant surroundings. (www.indiana.edu)

The room where documents for the storeroom are received is particularly badly hit by the fumes from the engine room, while in the library storeroom “fumes, probably from the sewers, fill this cellar with odours which are sometimes unbearable to those who work there”. Few offices in the basement have windows, and for staff fortunate enough to work in offices with daylight “their only view is of the chassis of the motors parked in the yard”. All in all, the basement resembles, according to Weber-Bauler, the inside of “an ill-designed and ill-constructed ship; it is the worst place of the whole building”.

Smell is also an issue on the mezzanine that is attached to the back of the Palais Wilson, where the League’s verbatim reporters are housed. Here rooms are not only small and crowded – during Assemblies five people are working in each room – the lavatories are also poorly ventilated, allowing smells to filter into the corridors.

The garden of the Palais Wilson (www.indiana.edu)

Leaving the Palais Wilson, we walk through the garden, away from the lake, and take a stroll in the streets behind the former hotel, where four different buildings serve as extra League office sites. One building, in the Rue des Paquis, just opposite the Palais, is in good condition and offers excellent working conditions with light and spacious rooms.

The same cannot be said for an apartment building in Rue Rothschild, where, among other things, the League’s typing pool is located. A cheap house built for small families of modest means, the rooms here are distinctively small and dark and most of them are overcrowded and noisy: “When we consider, in addition to the gloom of the north light, the noise made by the machines in these cramped and low rooms, we see that the working conditions of most of the typists are by no means satisfactory”.

The last two houses on our tour are two villas accommodating the internal, administrative services. In one of the villas, the head of the department, H.R. Huston, and his three assistants have decent offices with good lighting. However, the adjacent offices are crowded, holding up to 12 persons, with the air quickly becoming unbearably thick with cigarette smoke. Both villas are rundown and in critical need of repair. The villa that accommodates Huston and his staff is “a gloomy dilapidated building, the ground floor of which has never been repaired, and which still has wallpaper and paint dating from the middle of the last century; it is quite impossible to keep the place clean. The only good feature is the height of the rooms (3.30 m.)”

Internal services (www.indiana.edu)

Overall, the pattern that emerges from our tour is one of an organization that is clearly bursting at its seams. While the higher officials and their staff are still housed under decent conditions, chiefly in the front of the main building, almost all other members of staff have been squeezed into insufficient office spaces at the margins of the main building or in cheap, run-down buildings in nearby streets. The staff of the middle and lower grades, situated in the wings of the old hotel building and in the apartment building in Rue Rothschild work under rough conditions, while staff of similar rank working in the villas, in the attics or in the basement of the main building seem to be working under downright unhygienic and dangerous circumstances.

When Weber-Bauler drafted his report, he really did not need to convince anybody about the inadequate conditions of the Palais Wilson. Already in 1926, the League Assembly had decided that a new headquarter was needed. However, due to problems with the Swiss planning authorities and disagreements about who should design the new headquarter and what it should look like, it took a full ten years before the new Palais des Nations was completed.

It is one of the many ironies of the League of Nations that by the time the new Palais des Nations with its 440.000 m3 and 900 offices was finished, it wasn’t really needed. Due to the global economic crisis and increasing political tensions, funding for the League was diminishing through the 1930s and by the end of the decade the staff had been reduced to around 400. During the Second World War only ca. 100 people inhabited the enormous new building. However, after the Second World War the Palais des Nations did become the busy international hub it had been designed to be as it became home to the UN’s European office. Today it is second largest of the four UN office sites with 1600 employees, 8000 annual meetings, conferences and events and 100.000 visitors.

The Palais Wilson today (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Geneve_Palais_Wilson_2011-08-05_08_11_12_PICT0049B.JPG)

The Palais Wilson itself has also made a comeback as an international organization headquarter. In the decades after the League moved out, the old League building went through some turbulent years; it was used by various Swiss government departments, then the University of Geneva, before briefly reappearing as a hotel. Meanwhile, the building was falling into serious disrepair; it had begun subsiding into the lake embankment, the sandstone façade was crumbling and pigeons had started lodging in the loggias. After fires in 1985 and 1987 further damaged parts of the building, Swiss authorities decided to renovate the building with the aim of making it once again a headquarter of an international organization. The aim of the extensive renovation, conducted between 1993 and 1998, was to restore the building to its original state, stripping the façade of later additions and recreating the original décor down to the ‘real’ false marbles and flower stencilled walls. After the renovation, the building was made available at a preferential rent to the UN and today it is home to the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). It is another small irony that the staff of the OHCHR soon outgrew the Palais Wilson so that today part of the 700 employees are housed in the Palais des Nations.

Sources:

“Report by the Medical Adviser on the Hygienic Conditions of Work in the Secretariat of the League of Nations”, (signed L. Weber-Bauler, 14 February 1930), Commission of 13, 1930, Com. 13/16-32, League of Nations Archives, Geneva

“The League Building”, Information Section, March 1937, Seán Lesters Papers, folder 203/67, UCD Archives, Dublin

http://www.geneve-int.ch/en/palace-nations-monument-peace

http://www.geneve-int.ch/palais-wilson-memory-and-hostage-geneva